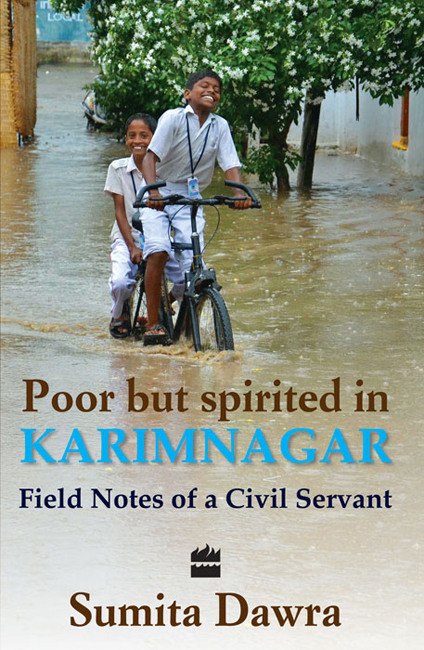

For the people of Karimnagar, to whom I gave my soul

and they gave it back to me, evolved and enriched

Contents

In the introduction to their book Super Freakonomics, Levitt and Dubner wrote, If you had the option of being born anywhere in the world today, India might not be the wisest choice. Despite its vaunted progress as a major player in the global economy, the country as a whole remains excruciatingly poor. Life expectancy and literacy rates are low; pollution and corruption are high. In the rural areas where more than two-thirds of Indians live, barely half of the households have electricity and only one in four homes has a toilet. I cannot contest this statement factually. However, being an Indian, I can say if I had a choice to be reborn, I would choose India as my place of birth. Not because I have had a wonderful existence in the country, but because of the different challenges it exposed me to that made my life richer.

Among other things, India has vast populations of widely disparate people coexisting within the same nation in a strange karmic fashion. Some of the wealthiest in the world live alongside millions of the most impoverished; the best brains anywhere in the world have also sprouted from a land with the largest global population of the illiterate. Such contrasts raise many fascinating and intriguing questions. They also pose the challenge of merging these contrasting worlds into one, where the marginalized populations also transcend the poverty trap and progress to more acceptable levels of human life.

Having worked as an administrator in India for over two decades, with about thirteen years in the districts of Andhra Pradesh in various capacities, I have had the opportunity to look at the world of the have nots closely. A world where children dropped out of school to help a widowed mother graze cattle, or tend to a sick father as the mother went out for her daily coolie labour or simply mind younger siblings at home as both parents went out to work. A world where entire families of power loom weavers took to committing suicide out of sheer hunger and desperation. A world where the hard work of the farmer brought him bumper crops only to face the struggle for a fair price for his producea rich harvest that still did not promise him freedom from poverty and debt. And this led to pertinent questions on why the region remained poor and backward despite decades-long implementation of ambitious, well-meaning developmental programmes of the Central and state governments.

Particularly my three years tenure as the collector of Karimnagar district of Andhra Pradesh gave me a unique insight into the forces that work to help this world progress, as well as the forces that work to preserve this microcosm as it is. Located in the north-western part of Andhra Pradesh, Karimnagar is one of the ten districts of the state in the Telangana region once ruled by the Nizam. With a population of thirty-eight lakh people in 2011, it is the sixty-seventh most populous district in the country out of a total of 640. It is also ranked the 250th most backward district of the country. Located on the banks of the Godavari River to its north, the district has land ranging from the ayacut under assured irrigation of the Sri Ram Sagar Project (SRSP), to dry areas totally dependent on the monsoons, and the forested inaccessible villages cut off at times by fast-flowing monsoon vagus (streams). in India.

The district is a miniature replica of the country with respect to the coexistence of the two worlds of the rich and the poorthe wealthy rice millers who coexist with malnourished families in the dry, upland villages; home to an erudite prime minister, it also has child labourers who worked in the roadside liquor shop serving truck drivers. Karimnagar is spread over a sprawling geographical area of 11,823 sq. km, consisting of 1,200 villages and five towns. As collector, I was the convergence point for the state government for implementation and review of all developmental programmes. These related to, for instance, poverty alleviation, education, health care, agriculture, water and sanitation, urban governance and infrastructual development.

My years in the districts of Andhra Pradesh gave me unique insights into the mechanics of programme implementation at the field level, a perspective one may not get living in the big cities of the country or the world. I got acquainted with social welfare pensions required for the physically handicapped children and the famished widows in the slums of Gudivada town in Andhra Pradesh; I was privy to the stories of children in the Naxal-dominated forest belt along the Godavari River who had never been to school, yet whose passion for learning made them clear the board exams in a matter of months; I was shockingly aware of the children who died almost overnight during the outbreak of an epidemic in Karimnagar district, possibly of reasons connected with malnutritionparadoxically in a district that has one of the highest paddy outputs in the state. What were the interventions that were really needed, but which the system had been unable to deliver? And what can we possibly do to make the nation free of the scourge of hunger and want, once and for all; promote service delivery systems that produce outcomes of development; and institutionalize systems of better governance?

At the same time, ambitious programmes of the Central and state governments are being implemented in the field. Though designed to resolve endemic issues in different areas, there are ways in which these programmes could be implemented differently to deliver better results. It is with the intention of sharing my insights from the field and my learning on different ways of doing things which might work better that I have penned this book. Poor but Spirited in Karimnagar looks at the story of development as it is unfolding in the field, at how things are working presently, what are perhaps the changes required and how the changes could translate into the outcomes that we, as a nation, have always aspired for. There are voices from the field that we need to listen to and act on. Voices of the stakeholdersthe people for whom the programmes are meant, as well as wisdom of the local political and official functionaries implementing these programmes.

Divided into several chapters, the book deals with experiences in implementation of schemes and programmes in the field of poverty alleviation, education, health care, agriculture, water and sanitation, and urban governance. While I have shared stories of my life in the districts, as a government representative trying to implement government programmes to the best of my abilities, I have also taken the liberty of sharing my thoughts on how things could work better. Some of my greatest learnings have been from the people themselves, their local leaders and the district- and state-level representatives. The book aims at sharing these experiences and learnings, to stimulate thought processes for achieving more effective governance in our country. It aims at adding to the ongoing dialogue on how to better develop India, a great nation that has one of the highest growth rates in the world, but one of the lowest ranking in the human development indices. A paradox that needs a quick resolution in order to give a better life to the citizens of the country.

Next page