Also by Rob Ruck

Steve Nelson, American Radical, with Steve Nelson and James R. Barrett

Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh

The Tropic of Baseball: Baseball in the Dominican Republic

Rooney: A Sporting Life, with Maggie Jones Patterson and Michael P. Weber

Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game

2018 by Robert Ruck

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2018

Distributed by Two Rivers Distribution

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Ruck, Rob, 1950- author.

Title: Tropic of football: the long and perilous journey of Samoans to the NFL / Rob Ruck.

Description: New York: New Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017059415 | ISBN 9781620973387 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Football playersUnited StatesBiography. | Football playersAmerican SamoaBiography. | National Football League. | American SamoaBiography.

Classification: LCC GV939.A1 R83 2018 | DDC 796.33092dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017059415

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by Bookbright Media

This book was set in Fournier MT and Gotham

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Omar vive!

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

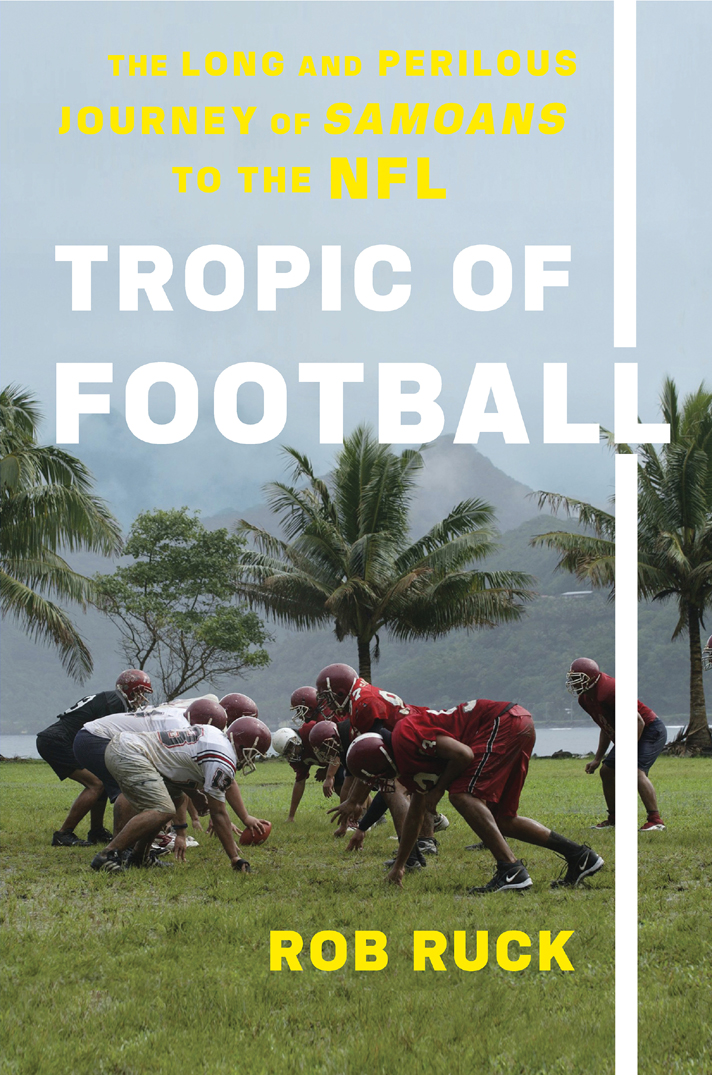

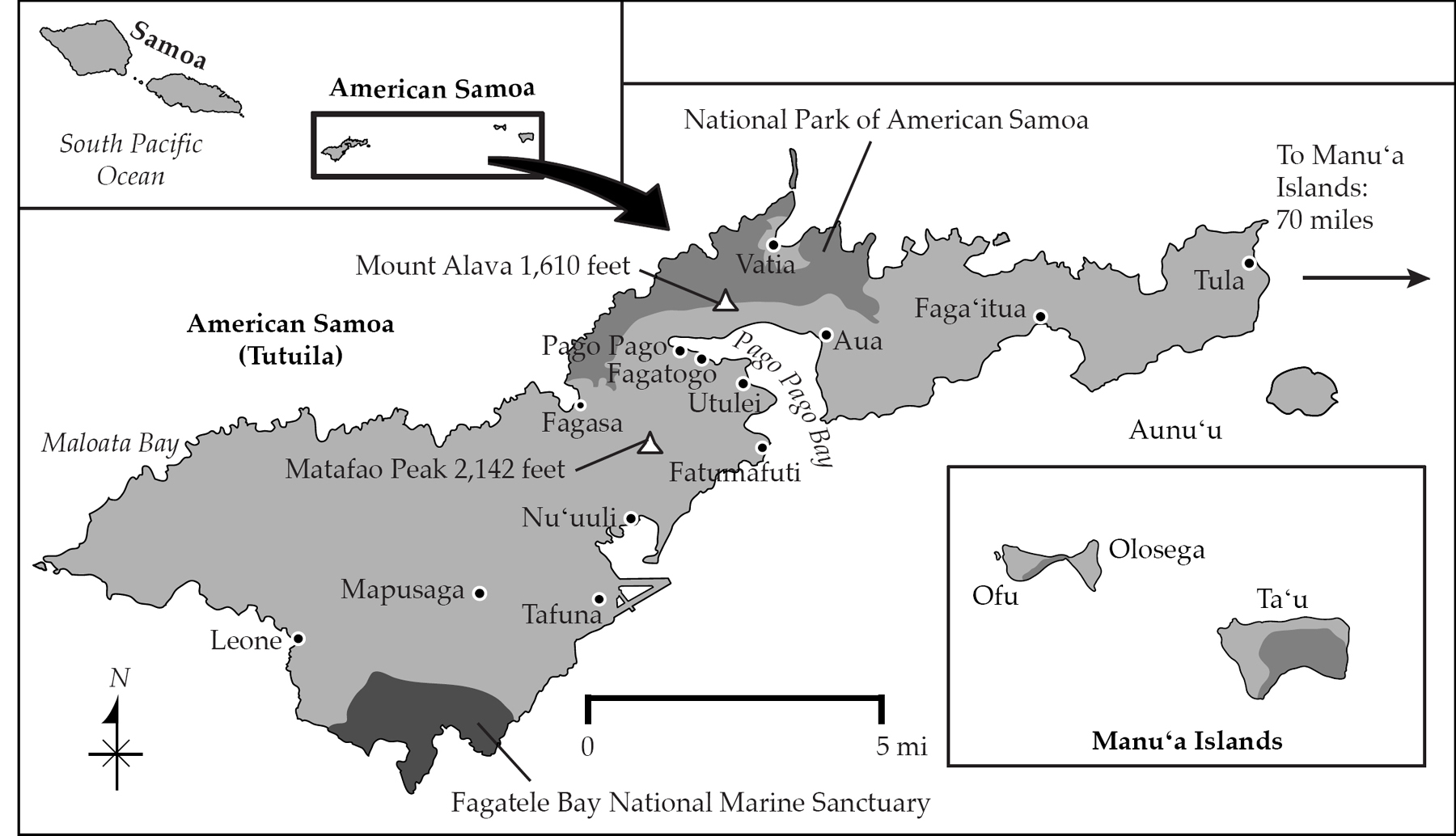

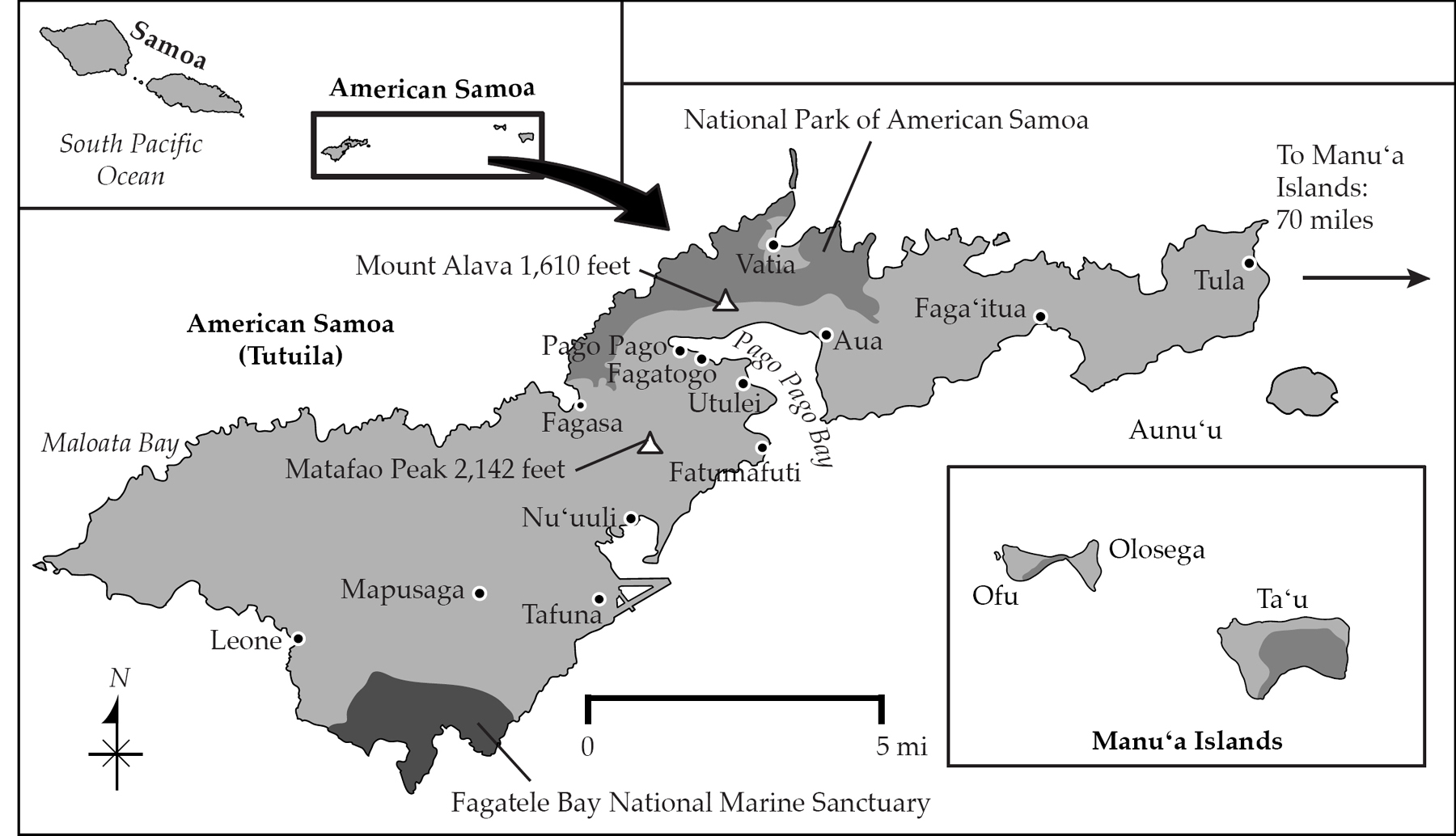

S everal high school football squads cluster on the sidelines of Veterans Memorial Stadium on a July morning in 2013. Rain scuds by on its way from an angry South Pacific Ocean to the green-slathered mountains that form the spine of Tutuila, the principal island of American Samoa. Its a narrow volcanic uplift about nineteen miles long, never more than five miles wide. Suddenly, players from two schools break into haka, the Maori challenge appropriated by teams throughout the Pacific. Two swarms of gesticulating players advance toward each other, contorting their faces, rhythmically slapping thighs and chests, and bellowing out Samoan phrases with guttural ferocity. A few men on the sidelines shake their heads, anticipating trouble.

Ryan Clark, the Pittsburgh Steelers defensive back, glides quickly into the space between the two squads. When the players converge, Clark disappears amid the scrum. But its all good. The players are not throwing punches; theyre jumping up and down like pogo sticks, yelling and hugging, and Clark is as amped as the boys. This aint about football, Clark yells as he emerges from the celebration. This about Samoa!

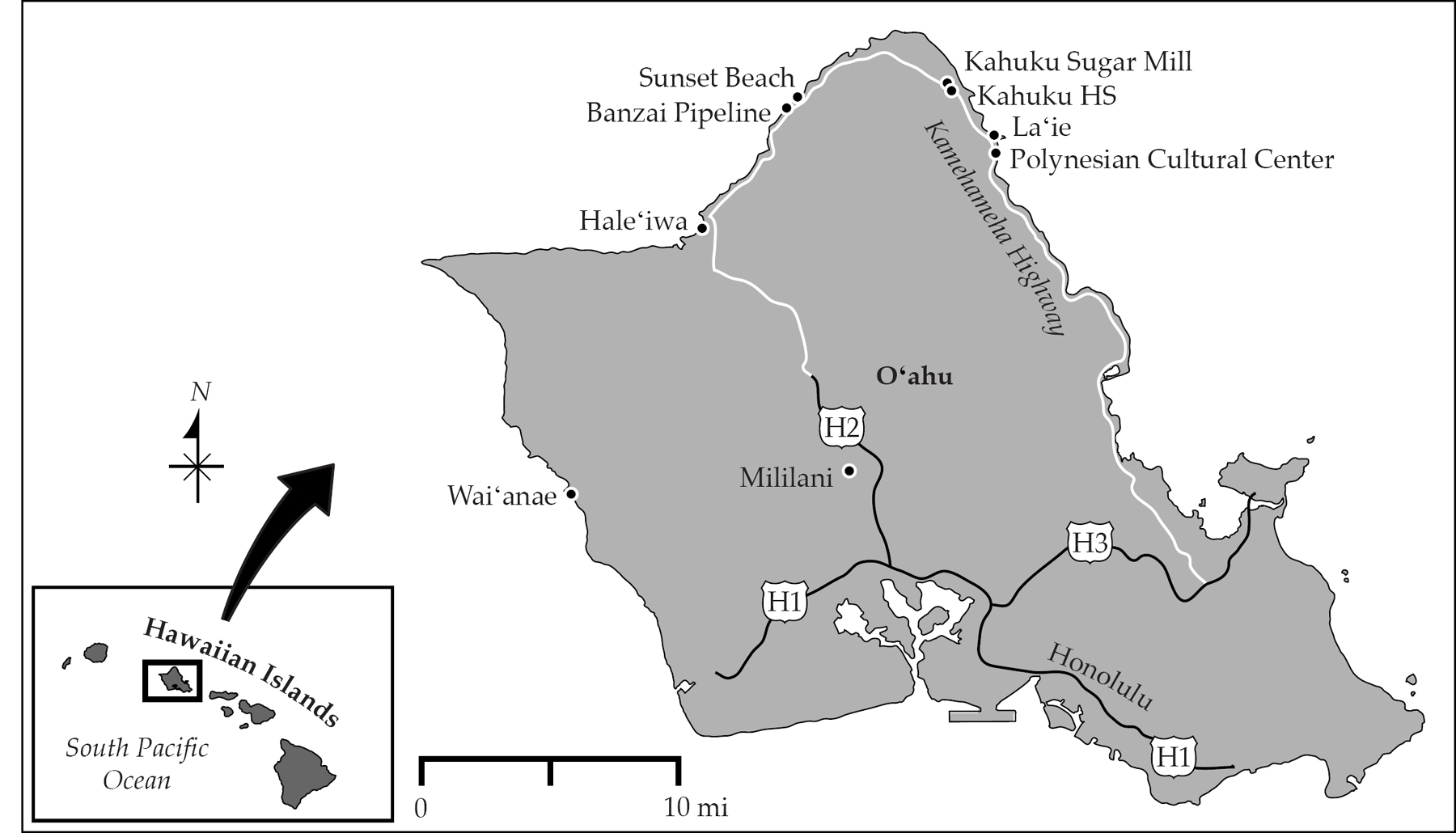

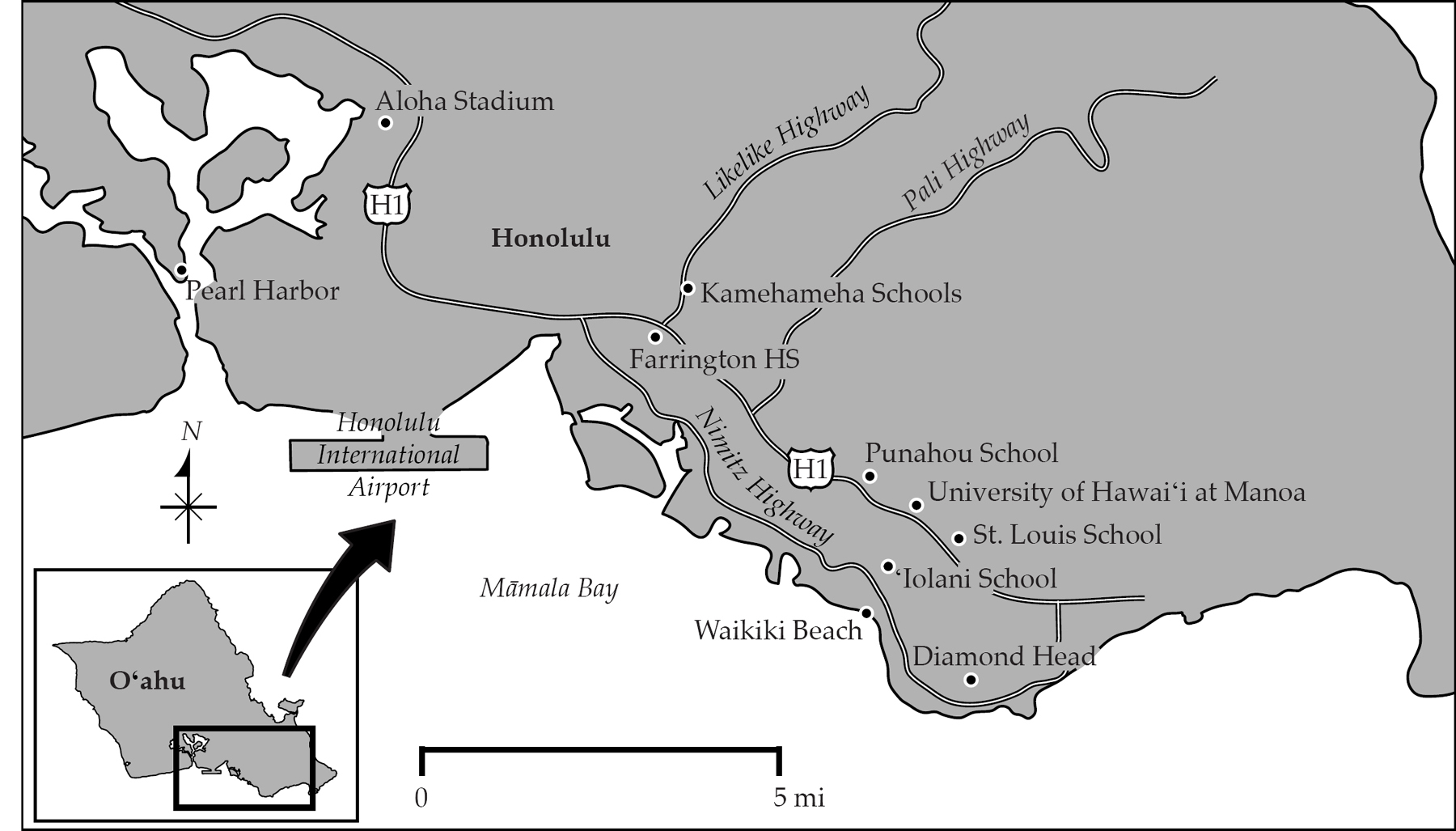

Football in the United States is at a crossroads, the sports future imperiled by the very physicality thats driven its popularity. The number of boys playing football in high school or on a team belonging to Pop Warner, the nations largest youth program, plunged over the last decade as the neurological, physical, and fiscal costs of the game became more evident. More and more high schools are terminating their teams. But one group has bucked that trendPolynesians, especially Samoans, in American Samoa, as well as in Hawaii, California, Utah, and pockets of Texas and the Pacific Northwest where they have congregated.

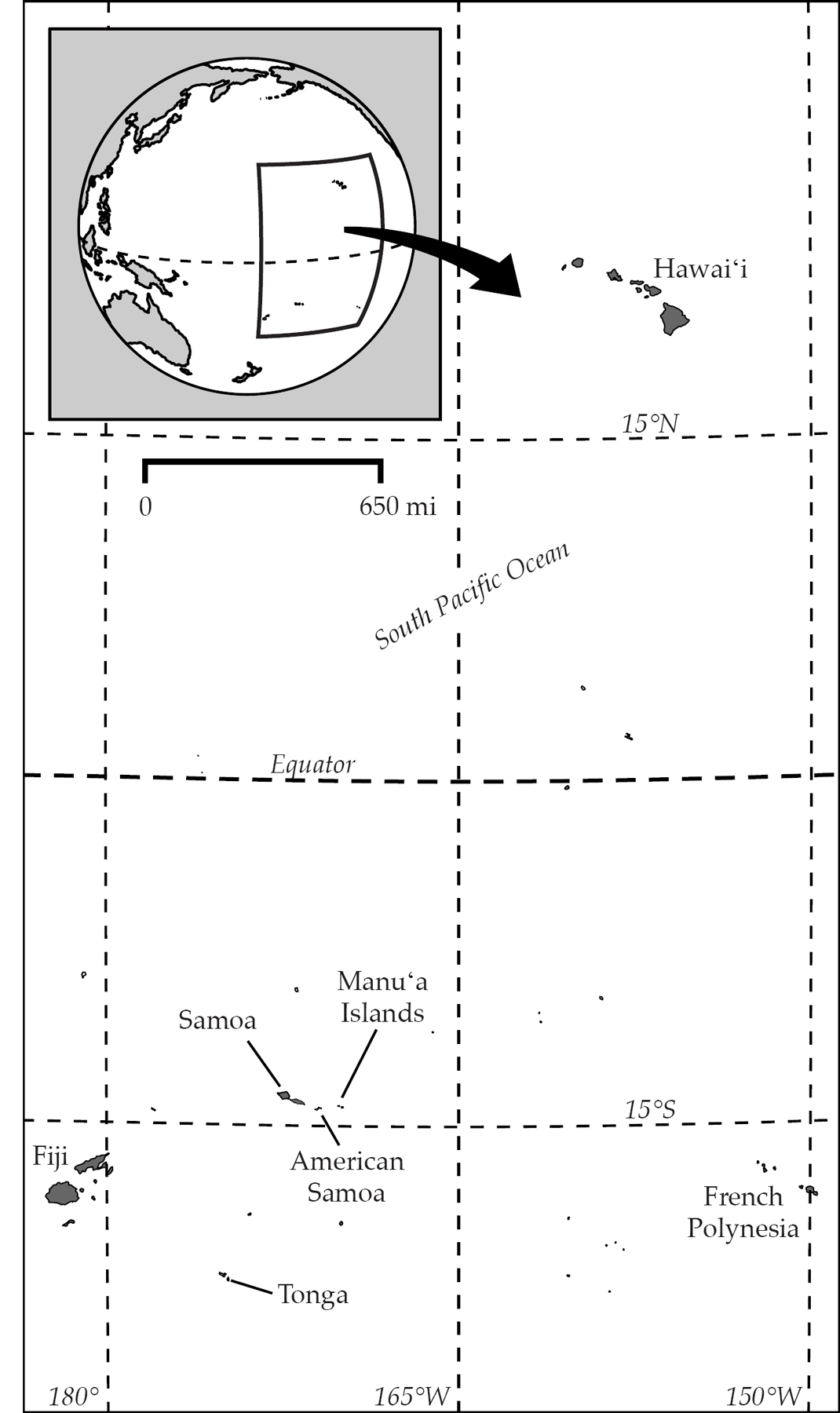

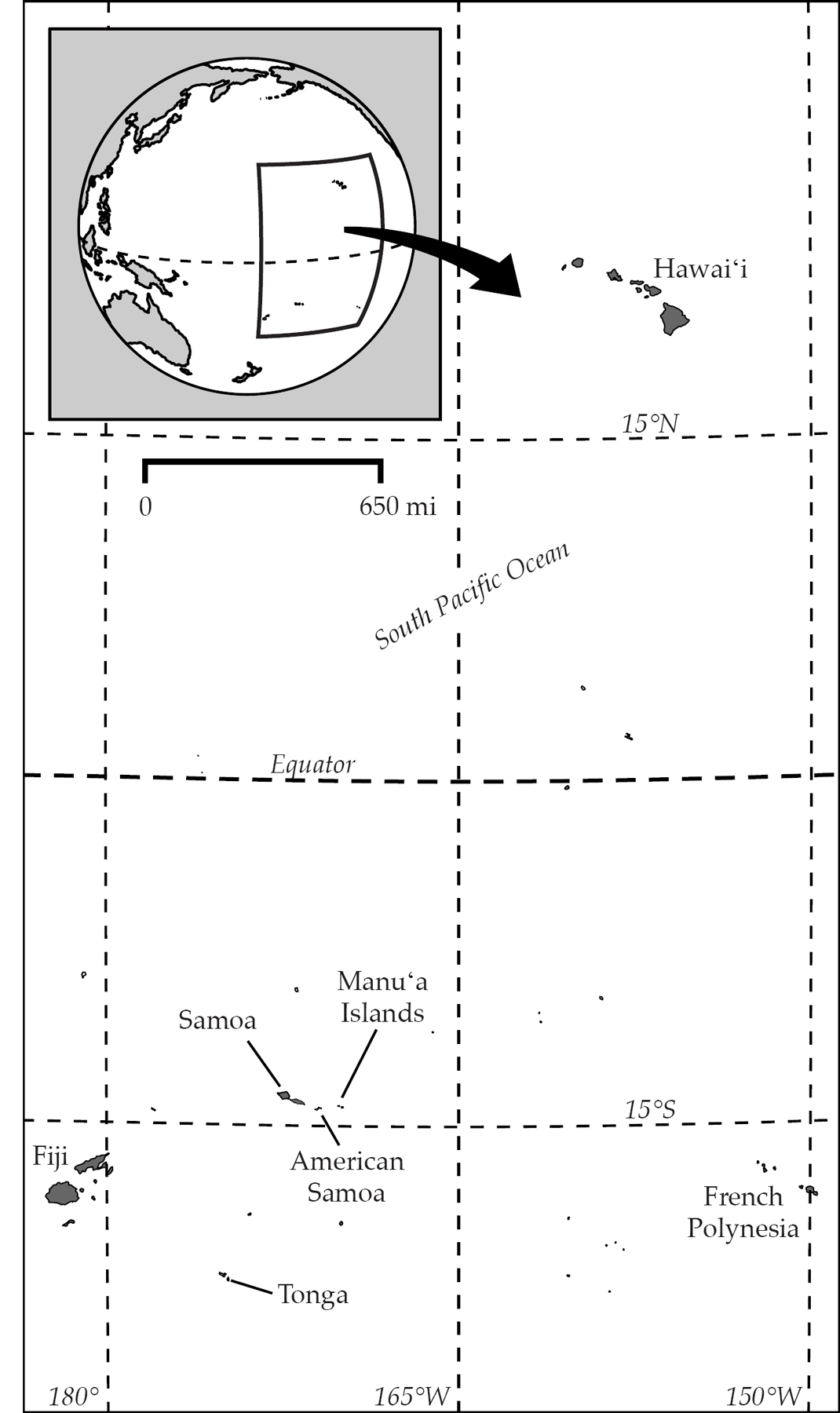

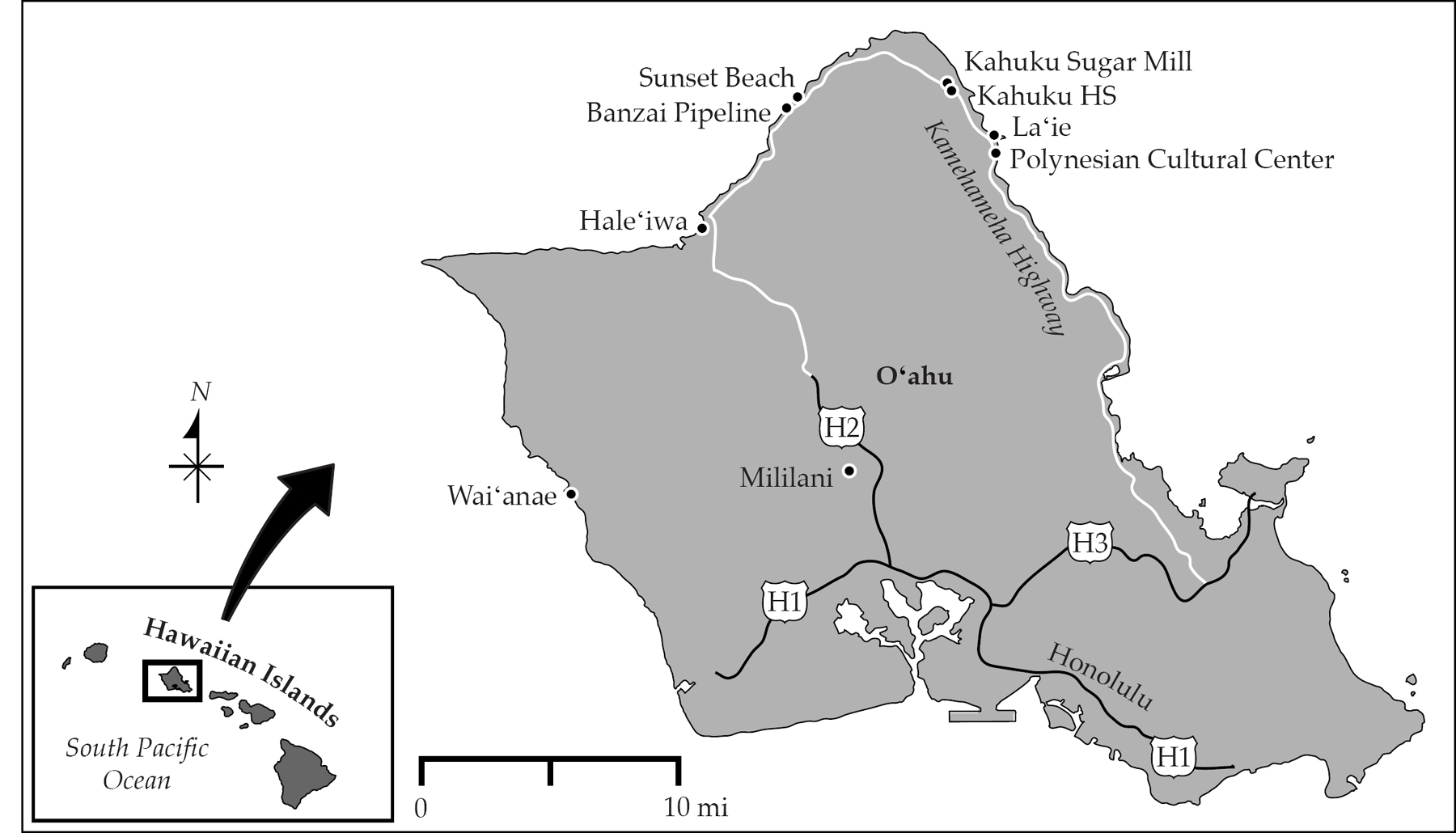

No culture has produced such an extraordinary number of athletes per capita as American Samoa and its fraternal outposts in the United States. The territory of American Samoa consists of Tutuila and its deepwater harbor at Pago Pago, the three islands comprising Manua, and a few coral atollsjust 76.1 square miles. These islands sit four thousand miles off the Pacific Coast, two-thirds of the way from Hawaii to New Zealand, and are the only place in the world outside the United States where football has taken hold at the grass roots, the only one that sends its native sons to the NFL. In the forefront of high school football in several stateside locales, Samoans have become the most disproportionately overrepresented demographic in the NFL and Division I college football. Junior Seaus 2015 induction to the Pro Football Hall of Fame and Marcus Mariotas Heisman Trophy honorsboth firsts for Samoansherald a growing wave of talent. The men coaching at Pittsburgh Steeler Troy Polamalus football camp on that rainy July day on Tutuila will tell you theres a tsunami of talent building in the Pacific.

Troy Polamalu brilliantly embodies that athletic aptitude. Although he settled easily into his surroundings, almost disappearing when he was off the field, the perennial Pro Bowl safety was the center of attention during a game. It wasnt just the hair, or the seemingly random way he dashed around before and during a play. It was his capacity to suddenly alter a games outcome. Given the liberty to freelance within Hall of Fame defensive coordinator Dick LeBeaus complex schemes, Polamalu behaved intuitively but paradoxically with great forethought. Unable to anticipate what he might do on any play, opposing quarterbacks shuddered at the sight of him.

In 2010, when Pittsburgh returned to the Super Bowl for the third time during Polamalus first ten seasons with the club, he was the NFL Defensive Player of the Year. Early that season, the Tennessee Titans had the ball on the Steelers two-yard line with little time left to play. If the Titans got the ball into the end zone, they still had time to come back and win the game. As Titan quarterback Kerry Collins rushed into position behind center, Polamalu stood absolutely still, processing how Tennessee approached the line of scrimmage, the game situation, and what he sensed they would do. Suddenly, he took three quick steps toward the line of scrimmage and launched himself forward. He was in the air before the ball was snapped, but not yet over the line of scrimmage. Clearing Tennessees crouching linemen by two feet, Polamalu unfurled his arms as he reached the apex of his trajectory. Plunging downward, he enveloped Collins just as the quarterback received the ball. Collins collapsed to the turf, with Polamalu on his back. As Polamalu popped up, Collins looked up from the turf and said, Dude, that was a great play.