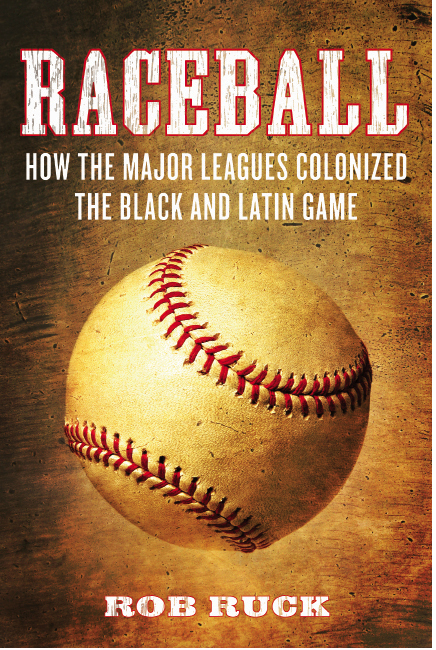

Raceball

HOW THE MAJOR LEAGUES COLONIZED

THE BLACK AND LATIN GAME

Rob Ruck

Beacon Press Boston

For Maggie

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Thousands of cameras flashed inside a packed Yankee Stadium as New York left-hander C. C. Sabathia rocked back and, with the relaxed delivery that had carried him to the Cy Young Award two years before, prepared to throw the first pitch of the 2009 World Series. Shortstop Jimmy Rollins, leading off for the Philadelphia Phillies, stared back at the Yankees portly ace. The matchup between these two men marked only the second time that the World Series had begun with an African American on the mound and at the plate. There was just as remarkable a backstory to the moment. Born less than two years apart in racially diverse East Bay communities in California, Sabathia and Rollins had taken startlingly parallel paths to Yankee Stadium that October evening. Neither man would have been there if not for RBIReviving Baseball in Inner Cities, a twenty-two-year-old program designed to stem the hemorrhaging of baseball in black America. Sabathia, who has called the dwindling number of African Americans in baseball a crisis, says that the game saved his life. It took me off the streets... kept me focused.

As cameras recorded that first pitch, Rollins, trying to bunt his way on, pushed the ball down the first baseline, right at the Yankees Mark Teixeira, who tagged him out before he reached the bag. Teixeira, the descendant of Portuguese and Italian immigrants, tossed the ball to second baseman Robinson Cano, who grew up in San Pedro de Macors, the Caribbean town best known for churning out major league ballplayers. Cano rifled it to Derek Jeter, the son of a biracial couple from Michigan, who relayed it to Alex Rodriguez, a Dominican American who had been so torn between which country to play for in the inaugural 2006 World Baseball Classic that he ended up not playing at all.

While the ball ricocheted around the infield, Johnny Damon, an army brat of Thai, Croatian, and Irish heritage; Dominican Melky Cabrera; and Nick Swisher, a second-generation major leaguer from West Virginia repositioned themselves in the outfield. Puerto Ricos Jorge Posada, one of four Yankees seeking a fourth championship ring, settled back into his crouch behind home plate while Panamanian Mariano Rivera and Dominican Pedro Martnez watched from opposite dugouts. The two pitchers, both destined for the Hall of Fame, switched effortlessly from Spanish to English as they joked with teammates from Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Panama, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and the United States. Meanwhile, Yankees designated hitter Hideki Matsui, one of two Asians in the Series, worked on his Teddy Roosevelt imitation. Talking softly but carrying a big bat, the player whom Japanese fans call Godzilla would earn Most Valuable Player honors at the Series end.

Sabathia, the recipient of the largest contract ever paid to a pitcher in the history of baseball, and Rollins, the 2007 National League MVP, were not the only African Americans on the field. Slugger Ryan Howard had powered the defending champion Phillies into the postseason, and shortstop Jeter captained the Yankees as he burnished his own Hall of Fame credentials. The moment was one reminiscent of the United Colors of Benetton advertising campaign, with players of mixed-race and non-European ancestry accounting for almost two-thirds of the starting lineups.

But the array of African Americans, Latinos, and Asians on the field masked a profound ironyAfrican Americans, who had once fought to integrate baseball, have largely left the game. The share of black ballplayers in the major leagues has plunged by two-thirds since its historic high in the late 1970s. And although Major League Baseballs workforce has a new international complexion, its globalization has come at the expense of baseball beyond U.S. borders, especially at the games withering grass roots. Power remains concentrated in the hands of white owners and front-office personnel. Few African Americans and Hispanic or Latino Americans can be found among the ranks of managers, general managers, and owners. More than half a century after baseballs integration, these positions remain largely white preserves.

Nowhere is the demographic reversal of who plays baseball more evident than in the Caribbean. While African Americans are disappearing from baseball, Latin Americans have stormed major league diamonds in record numbers. African Americans now hold fewer than one-tenth of all big-league roster spots, while Latinos fill more than a quarter of them and make up about half of those in the minor leagues. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, Latinos dominated All-Star lineups, swept individual awards with stunning regularity, and even powered the Boston Red Sox to their first World Series titles since 1918.

David Ortiz and Manny Ramirez were the toast of New England in 2004 as they led the Red Soxs comeback from a three-games-to-none deficit to beat the New York Yankees in the American League Championship Series and go on to win the World Series. Dominicans and Bostonians alike relished their victory over the Yankees. It had not been that way in 1918, the last time the Red Sox had captured the World Series, when the yanquis were occupying the Dominican Republic. U.S. Marines had invaded in 1916, a year after seizing Haiti. American troops stayed for eight years on the Dominican side of Hispaniola, longer in Haiti, and returned again in 1965.

It was baseballs Yankees who came to the DR in 2009, when a dozen of the teams Latin players and coaches, including senior vice president Felipe Lopez, visited the presidential palace in Santo Domingo to meet with President Leonel Fernndez. The celebration continued that evening: Mariano Rivera, who was on the mound when the Series ended, threw out the ceremonial first pitch to open a Dominican League playoff game at the 16,500-seat Estadio Quisqueya. It was an appropriate salute to the Caribbean nation in the forefront of the Pan-American pastime. It also reflected how much the New York Yankees, a team slow to cross the color line, had adopted Latin players. Their playoff roster included ten Latinos40 percent of the teambut only three African Americans. Dominicans alone outnumbered their black teammates.

The visit to Santo Domingo was part of a months-long, multinational victory lap that began with the traditional ticker-tape parade up Broadway through the Canyon of Heroes to City Hall. And though they brought their World Series trophy to a few local venues as well as Santo Domingo and then across the Pacific to Japan and China, there was no comparable display in black America. The club did not have a black cohort of players to match its Latin contingent. Nor could its three African American players carry the World Series trophy back to some representative black community in the United States where baseball still resonated. Baseball has become unhinged from daily life in black America, and what few black ballplayers remain are no longer as deeply rooted in black neighborhoods as Latino players are in theirs. Despite what baseball once meant to black America, African Americans currently matter less in baseball than at any time in the last fifty years.

The Latin wave, on the other hand, has yet to crest. The Dominican Republic alone contributed as many players to baseballs final four playoff teams in 2009 as the entire African American community, even though the United States 38 million African Americans outnumber Dominicans four to one. Overall, playoff rosters had twice as many Latinos and Hispanic Americans as African Americans. The disparities are even greater across the major and minor leagues. Although an increasing number of players, like U.S. citizens overall, have multiracial identities, these trends are stark and undeniable.