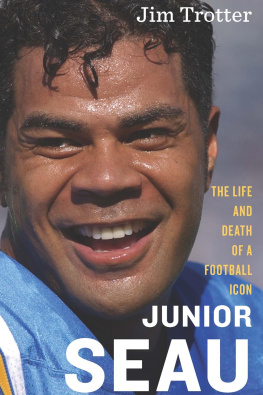

Copyright 2015 by Jim Trotter

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-23617-2

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover photographs Mark A. Brown/Icon SMI/Corbis

e ISBN 978-0-544-23714-8

v1.1015

To my motherMy biggest cheerleader.

To my familyThanks for your patience.

To the Seau childrenIf greatness is making those around you better, your father achieved greatness many times over in his 43 years.

To JuniorMiss you, bud-deee.

Introduction

Instantly, the room fell silent.

The 1999 NFL season had been over for roughly a month when members of the San Diego Chargers coaching and personnel staffs met in a second-floor office at their training facility.

They were there to discuss the roster, and one by one, they reviewed each player, identifying his strengths and weaknesses and overall value to the team. Eventually they got to Junior Seau, their perennial Pro Bowl linebacker who had just finished his 10th season.

The conversation didnt last long, but near the end of it, almost in passing, veteran linebackers coach Jim Vechiarella said: Its not going to end well for this guy.

Everyone was stunned. It was as if a rock had crashed through the window. They looked around at each other as if to say, Did I just hear what I think I heard?

Junior was the local boy who made gooda gifted athlete at Oceanside High School and the University of Southern California who went on to be drafted fifth overall by the Chargers in 1990. He was beloved in the community and revered by his teammates. He owned a popular restaurant and had some of San Diegos most prominent power brokers on speed dial.

Not going to end well? Junior Seau?

It was chilling, said Billy Devaney, the teams director of player personnel at the time. Vech had been around. He was kind of a crusty old guy. But he wasnt saying it to be negative. It was more out of concern.

He was worried about Junior and life after football, said former head coach Mike Riley. Looking back...

Riley paused before continuing: For a guy like Junior, football is more than an occupation. Its life.

And in this case, death.

On May 2, 2012, only two and a half years after concluding a 20-season NFL career that included 12 Pro Bowl berths, eight All-Pro selections, and two Super Bowl appearances, Junior retreated to a second-floor bedroom in his beachfront home in Oceanside, California, leaned back on a bed, and put a .357-caliber revolver over his heart. Then he pulled the trigger.

The answer to why the 43-year-old killed himself is as complex as the question is simple. There were addictions or dependency to alcohol, prescription meds, gambling, and women. There was brain damage from two decades of violent collisions in the National Football League. There was the suffocating pressure of having to be a human ATM for a community-sized family, not to mention the shame of feeling he had failed because he was headed for bankruptcy despite having left the game with a financial portfolio that didnt require him to work in retirement unless he chose to do so.

Few people knew the severity of his pain or his problems because he never pulled back the curtains to let anyone see it. Instead, he hid everything behind a smile so bright it could light up a stadium. He was a master of manipulation and compartmentalization, often telling people what he thought they wanted to hearwhat would make them happy and create the least amount of dramarather than what he was really thinking or feeling.

He did it with the women in his life, making each one feel as if she was the only one who mattered by telling her that he loved her; in reality, he was saying the same thing to at least one other woman at the same time. He did it with family members, telling them he was unaware that his foundation director and personal assistant had blocked their attempts to reach him or get money from him when, in reality, he was the one telling her not to give it to them. He did it with his trainers and teammates, hiding injuries and seeking physical treatment in private to perpetuate the image of himself as being more myth than man. And he did it with friends, telling them everything was great when, in reality, his life was spinning out of control.

Presenting an image of happiness and control was as important to him as presenting an image of strength. While growing up, he and his five siblings were told regularly by their mother to go into the world and make happy, which was what he tried to do. His smile was as disarming as his sculpted six-foot-three, 255-pound physique was intimidating. He loved to laugh and sing, even though his voice was often off-key. His playfulness sometimes resulted in comments or jokes that were politically incorrect, but he could get away with it because everyone knew there wasnt a malicious bone on his skeleton. Even Nick Saban and Bill Belichick, coaches whose public personas are as dour as Juniors was jovial, accepted his verbal jabs because they knew the words came from a good place.

The reality, however, is that we dont really know our athletic heroes, as much as we think otherwise. We see only the facade, the parts that they want us to see. This isnt to say Junior wasnt a good man. He was. He gave to those around him without ever asking for anything but a smile in return. Bringing joy to someone else brought pleasure to him. He called everyone Buddy, though in his own unique way. It wasnt BUD-DY, two quick syllables, but BUD-DEEEE, with him hanging on to the DEEEE as if it were a note in a song.

Countless people wouldve been there in a heartbeat if they had known he needed help, but he viewed asking for help as a form of weakness. The few who did reach out to him were pushed away or kept at a distance. On those occasions when he felt he had bottomed out, he told people close to him that he was unhappy with himself and wanted to change. But those moments of clarity were fleeting and quickly replaced with more women, more alcohol, and more trips to casinos.

The two things that he told me that really gave him peace were his children and that surf, to be able to go out there and surf those waves, said Rodney Harrison, a teammate in San Diego and New England. They gave him that peace for that moment.

His longboard was so big, it could have been mistaken for a kayak, and on most days in the off-season he made a point of walking across the narrow road in front of his home, down the 12 concrete stairs to the shore, then through the sand and into the cold yet comforting Pacificthe same Pacific on which he had body-surfed as a kid.

The weekend after his death some 200 surfers made that same trek and paddled offshore. New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees was among them, despite he and Junior playing together for only two seasons in San Diego. He was more than just a great football player, Brees said. He was the heartbeat of the team and the city for a long time. Everywhere you went, he was like a legend. He was like family to everybody. Ive never played with someone whom the guys on the team respected more.

That respect extended beyond the locker room. In December 2010, Mark Davis, the freckle-faced, gravel-voiced son of legendary Raiders owner Al Davis, chose to stay overnight in San Diego after a 2813 defeat of the Chargers before driving to Palm Springs for a brief getaway. He was hungry and wanted to watch that nights NFL game between the Ravens and Steelers, so he went to Seaus The Restaurant.

Next page