Adonia Lugo - Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance

Here you can read online Adonia Lugo - Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Adonia Lugo: author's other books

Who wrote Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

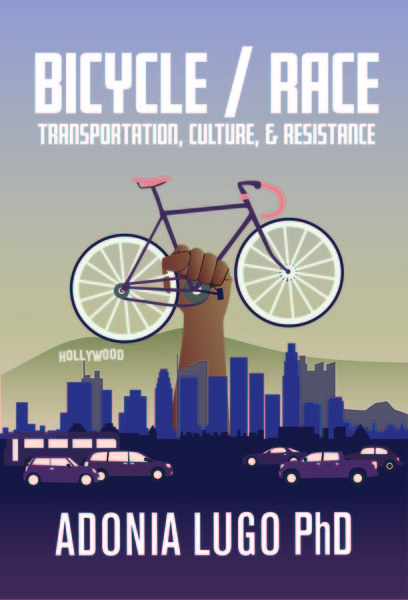

Bicycle / race

Transportation, Culture, & Resistance

Adonia E. Lugo PhD

Microcosm Publishing

Portland, Oregon

BICYCLE/RACE

Transportation, Culture, & Resistance

Adonia E. Lugo, 2018

This Edition Microcosm Publishing 2018

First published Oct 9, 2018

ISBN 978-1-62106-998-0

This is Microcosm #246

Edited by Elly Blue

Cover by Katja Gantz

Book design by Joe Biel

Distributed by PGW and Turnaround in the UK

For a catalog, write or visit:

Microcosm Publishing

2752 N Williams Ave.

Portland, OR 97227

www.microcosmpublishing.com

Microcosm Publishing is Portlands most diversified publishing house and distributor with a focus on the colorful, authentic, and empowering. Our books and zines have put your power in your hands since 1996, equipping readers to make positive changes in their lives and in the world around them. Microcosm emphasizes skill-building, showing hidden histories, and fostering creativity through challenging conventional publishing wisdom with books and bookettes about DIY skills, food, bicycling, gender, self-care, and social justice. What was once a distro and record label was started by Joe Biel in his bedroom and has become among the oldest independent publishing houses in Portland, OR. We are a politically moderate, centrist publisher in a world that has inched to the right for the past 80 years.

Table of Contents

Part One: Transportation and Race in Southern California

Introduction : What Does Race Have To Do with Bicycling?

Jos Umberto Barranco was biking home from work on the sidewalk of a suburban road early one October morning in 2007 when an intoxicated young woman hopped the curb in her car and struck him. I read in the local paper that he had been a busboy at a nearby Dennys for seven years. I knew the winding street he had been biking down because it leads to San Juan Capistrano, my hometown. I had walked its length many times, and passed along it in a car even more. I knew the spots where curves made it hard to keep driving at the 45 mph speed limit, even though the other drivers behind you were not slowing down.

I read about this mans death at a moment of static in my life, when Southern Californias car culture was shouting over the reduce-your-carbon-footprint norms Id adopted during my college years in Portland, Oregon. I had recently returned to Southern California to start graduate school, and my boyfriend and I had chosen Long Beach as our home base during my first year of graduate school at UC Irvine because the regular street grid and neighborhood hubs reminded us of Portland. But in my new neighborhood, drivers quickly let me know that they didnt think my bike and I belonged on the road. Legally, I was in the right; bicyclists can lawfully use travel lanes. Culturally, I was wrong; he who can travel fastest wins. What Jos Umberto Barrancos death said to me was that this wasnt just a matter of vehicle choice, bikes versus cars. Race and class hierarchy were mixed up in how we traveled and whose safety mattered.

Once I started trying to wrap my head around this tangle of race, place, and mobility, I realized that Id known about it for a long time. I knew that Latinas and Latinos walked and biked around my hometown and region more than white residents did, and they were the ones who waited on corners for the infrequent OCTA bus service. I knew that the racism in south Orange County created a palpable feeling of unwelcome for immigrants, and people insulated themselves from it by getting into private cars and off exposed sidewalks as soon as they could afford to. I knew that being inside a car was the safeguard everybody was striving toward, in part because suburban sprawl made long commutes the norm. Now I noticed that most of the bicycle users I saw in Southern California had something in common with the folks walking and riding the bus: they were people of color. I later learned that black and brown men were overrepresented in bike fatalities nationwide. Jos Umberto Barrancos death was tragic; it was also typical.

While Id never questioned how it bled into transportation, I had been keenly aware of the racial segregation I grew up around because I didnt make sense in it. Identifying myself in the imperfect language of race and ethnicity, Im a half-Mexican and half-white woman. My brown skin and black hair express the genes of an Indigenous people whose name I dont know, and I grew up speaking English. Not fitting on one side of race divides could be lonely, but it also let me see how flexible the world could be because some people expected the world to bend to their will while others did the bending.

In 2007, witnessing that traveling outside of cars could be both ecologically virtuous (saving the planet, good for you!) and socially repugnant (what, you cant afford to drive?), I could see multiple sides. Wed learned long ago how harmful the shift to oil dependence had been for our planet, but people didnt want to give up their cars. In our cars we felt safe and powerful, and these feelings mattered a lot, especially for those who had to live under harsh conditions. Yet we needed to find ways to reduce our oil consumption; of that I was certain, too. I had just started planning my trajectory as a cultural anthropology doctoral student, and the conundrum of how to promote bicycling in a place dominated by the need for speed presented a potential site for turning a divided culture toward sustainability. In other words, it became my dissertation topic.

Bicycling was not the only alternative to gas-powered, single-driver travel, but the fact that it had a social movement promoting it meant that maybe there were people out there who had some thoughtful answers to my many questions. Besides the physical streetscape, what race and class systems limited our access to mobility? Who was thinking about the street safety of the people who were usually treated like a threat to public safety? Did bike commuting make someone seem unimportant, or did being an unimportant person make bicycling seem equally worthless? Why was bicycling so low-status in Southern California, when it had been a key part of Portlands appeal? Why was it normal to travel long distances between work or school and home in Southern California? What made a street safe or unsafe, and whose safety were we talking about?

What I would find through my research and through becoming a bike advocate myself was that only a few of us were asking these questions. The bicycle movement was divided over whether there was a connection between bicycling and race, because the U.S. bike movement was itself the product of a racially segregated society. Organized networks of white people promoting bicycling in the United States had waxed and waned since the 1880s, when the bicycle had been the height of new mobility. Wealthy men and women (but mostly men) enjoyed taking over roads on two wheels so much that they lobbied for massive expansion of the public road system. When the automobile took over as king of those roads in the early twentieth century, the bicycle gradually became a vehicle for people who couldnt drive, whether due to age, poverty, or lack of access to a drivers license.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance»

Look at similar books to Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.