Edited and compiled by Seetha Natesh

Designed by Ashish Verma

CHASING

GREATNESS

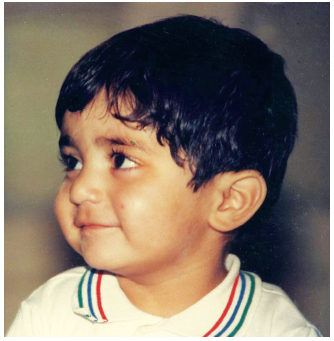

India at the Olympics focuses not just on the countrys participation at the Olympics but also the Indian athletes who created Olympic history. One such Olympic champion is Abhinav Bindra and this is how his remarkable story began.

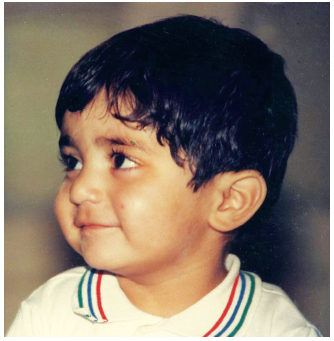

I was a fat boy, a normal gregarious kid, who wasnt keen on reading, hated physical activity and was ambivalent about playing sport. Physical training classes were akin to hard labour and I would find the flimsiest excuse to bunk them. The Doon School was my home briefly as a kid for a few years, but it didnt fit my personality. Lets just say I was a homesick mamas boy. Even though sport is one of the joyful escapes of boarding school, I wasnt intrigued. Watching, yes; playing, yes, but without any evident passion. Id attended a cricket Test at Lords in 1996 as a boy, watching Javagal Srinath send Michael Atherton in the first over, but this sport did not call me as a participant. For a while I played golf with my father and hoofed around a football, but I gave up easily. Call it a lack of talent. My father, bless him, tried. Every day, when I was in Doon School, he wrote me a letter. Every day, hows that for love? But his letters had one common theme: try sport, son. He had played sport as a boy, hed seen the passion with which it was followed when living in Denmark, and he believed sport allowed a person to develop himself and stand out. Studies were fine, but sport was a vehicle for recognition far beyond mere money. It offered, he believed, the highest glory.

Dad tried. He pushed. It didnt work.

And then I found something else.

Guns.

Like boys and fighter planes, these shining, smooth weapons had some mysterious, almost mystical, hold over me. Even now, like some familiar scent, I can remember the smell of gun oil from my childhood. My father had three weapons, a W.W Greener shotgun, a .22 Czech Bruno rifle, a Webley revolver. Once a month, I would sit fascinated, as he dismantled them, sliding cleaning rods into the barrel and coating them with oil.

I was about ten when my father first allowed me to shoot. He held the shotgun, I pulled the trigger. Quick to sense my fascination, he gifted me air guns on my birthdays, like those old Daisys which I could barely bend and collapse to feed pellets into. Theyre still stored in a lost corner of my house. My mother was nervous about a kid with an air gun popping away at cans and bottles, but surrendered to this addiction. It calmed me, it reassured me, it was mine. Entire afternoons would drift by with me loading, aiming, firing, reloading, as if this was some routine that perfectly fitted my personality. The individuality and solitude of shooting, the reality that any success or failure rested entirely with me, was intriguing. I began to get a strange sensation, as though this was something I was meant to do.

Like many kids, I was capable of acts of irresponsibility. In my case, it was persuading my maid and her daughter Tulsi to rest balloons and bottles on their head while I shot at them. The maids were brave, I was foolish. Fortunately, I was also a good shot. When my mother found out about my sniper impersonations, there was hell to pay. Human targets were understandably banned, but shooting wasnt discouraged, not even when her lawn became a carpet of broken bottles.

How does anything start, a career build? Passion first, chance next? Rana Gurmit Sodhi, who later became Punjabs sports minister and was a strong supporter of athletes, was a family friend and a fine shooter. He saw me breaking those bottles one day and there it began.

He sensed I had potential and suggested to my father that professional training could help me. My father needed a coach. Sodhis friend, Lieutenant Colonel Jagir Singh Dhillon, was one.

The colonel had been around guns all his life. Hed shot in the first national shooting championships in 1952 and had stopped only in 2004. He had shot at the Asian Games twice, in 1970 and 1978, and been a coach in 1982. And he had done one more thing. Hed shared a room with Milkha Singh. The colonel was then an aspiring shot-putter, his roommate a great runner under construction.

The problem was getting Dhillon to agree to coach me. Sodhi kept promising to set up a meeting but he was a busy man. But stubbornness was part of what defined me. So I took the initiative, sat at the computer and typed out this letter to the colonel. I was thirteen years old.

Sir,

By now Mr Rana Sodhi must have got in touch with you regarding coaching me for shooting. Sir, I am very interested in shooting but dont know how to go about it. I humbly request you to kindly coach me. I am prepared to work as hard as I can & make you feel proud of me one day.

Please let me know the timings, fee, as soon as possible. I am ready to start working hard from tomorrow itself. Looking forward to being your student.

With respectful regards,

Abhinav Bindra

Sodhi had, in fact, already spoken to Dhillon. But the colonel was unsure about me. He thought, I waited. But the letter startled him. The clarity of what I wanted had an impact. I was ready, now so was Dhillon, and he sent word: Come.

I remember the day Sodhi took me there. I remember returning from school, skipping lunch, and going for the meeting, so full of apprehension and elation, like a boy before his first exam. I was immediately impressed with the colonel because he talked details. He asked me to come the next morning at 8 a.m. I was there at 7.45. It surprised him. He was an old school gent who thought the rich preferred not to sweat and those who sweated couldnt afford to shoot. My attitude altered his view. I love shooting and sweat, the challenge of hovering flies, the burn of the sun, the need to blank out one universe and get lost in another one. Cool rooms and carom werent my thing. Still arent.

We started with an Indian rifle with an open sight. It was a basic gun, with an I in the front and the U at the back for aiming. Then we went shopping for a better one, even if just a poor quality carbon dioxide powered weapon. The rifle is everything, it has to fit the shooter, like a tennis racket or a golf club; it is about feel, balance, weight, comfort. The sportsman doesnt want to think about his equipment, he has to just believe in it, trust it, and so quality matters.

I needed an air rifle, junior model, and after perusing shooting magazines, the colonel recommended a gun manufactured by Beeman Precision. My mothers sister, Tina Chopra, who lived in Sussex, New Jersey, in America, bought it and handed it over to my father, who was travelling there. In those days bringing a rifle into India was cause for nervousness, but my father paid the requisite duty and ten days after ordering my gun, there it was. I still have a photo of me with it. Some days I look at it and smile.

I trained every day with the colonel. No exceptions. He had a range built in his backyard, and under the shade of a friendly mango tree I chased greatness. We shot at old-fashioned paper targets that had to be reeled in on a pulley system, after every shot the paper changed and reeled back in place. A shooting jacket was ordered from Germany, a heavy, swollen tunic that helps stabilize the shooter, and in the 40-degree summer heat I wore it and shot. Bullet after bullet. Hour after hour. A table fan arrived one day and sat there like a sentinel, capable only of squeaking out hot air. I didnt care, I never complained, I only wanted to shoot.

Next page