Names: Earls, Felton, author. | Carlson, Mary, author.

Title: Voice, choice, and action : the potential of young citizens to heal democracy / Felton Earls and Mary Carlson.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: LCSH: Children and politics. | Childrens rights. | Youth Civil rights. | YouthPolitical activity. | Political participation.

WE DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO DEMOCRACYTHE TRUEST KIND OF DEMOCRACY THAT INCLUDES ALL ITS CHILDREN.

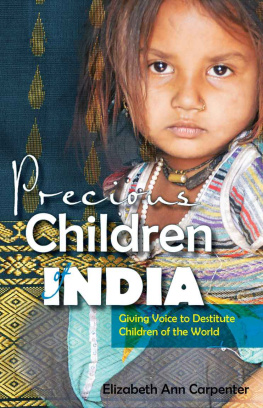

How can we adults claim to see our world clearly and completely without incorporating the perspectives of its youngest inhabitants, its children? Believe it or not, children can contribute insights and solutions to profoundly difficult circumstances confronting their communities. The question is not whether they have something to say but whether todays children will be encouraged and expected to voice their opinions, make informed decisions, and coordinate their chosen actions. What will we adultsparents, neighbors, educators, scholars, and leadersdo to engage them?

This book draws on childhood development science, intensive fieldwork, and real-world social action to show how to improve society by ensuring that children become respected participants in the public discourse. Our definition of children follows that of UNICEF, as the international standard: every human being below the age of eighteen years. In these pages, we explore how even very young people can be introduced to the idea of human rights and citizenship and provided with the tools to deliberate among themselves. Voice, Choice, and Action collects decades of research into one definitive text to demonstrate that children have the awareness and competence to claim citizenship roles in democratic society.

We show children doing just thiswhether growing up in a Chicago neighborhood riddled by violence, surviving homeless on the streets of Brazil, or facing the loss of parents to HIV in Tanzania. In Chicago, children initiated a probing dialogue to question the violence threatening their neighborhoods. In Brazil, children formed their own political movement to help forge a child rights statute in the countrys new constitution that changed the identity of children from that of lesser minors to that of empowered rightsholders. These successes helped to inform a fully developed Young Citizens program that was rigorously evaluated in Tanzania. There, young citizens started a public health movement in their local communities that led to a dramatic increase in voluntary testing for HIV, a critical intervention in a devastating national crisis.

To be sure, equipping a child to participate in public discourse begins in infancy. In Romania, we encountered abandoned infants living in state institutions by the thousands, denied the most basic social contact required to become fully human, let alone citizens. Yet nurture alone is not sufficient to give children voice, prepare them to make choices, and embolden them to take action. This is not charity. Rather, we need processes for discovering childrens social, communicative, and rational capabilities and supporting them in being recognized and respected as increasingly competent deliberative citizens.

The Young Citizens program described in these pages offers possibilitiesand does so at a vital moment in history. Across the globe, birth rates are dropping, in many places quite rapidly. As the worlds population ages, societies will depend ever more upon the open minds and boundless energy of children.

Today, in America, children are leading a national effort to tackle the crisis of gun violence. Around the world, children are coming together to awaken their communities and nations to the global health and ecological threat of climate change. Freshly inspired by their actions, we synthesize here the results of our long careers work. Framed in social theory, guided by scientific inquiry, and grounded in proven participatory practices, may innovations like the Young Citizens program help to bring more children into democratic deliberations, and to keep our democracies vibrant.

The science of human development must account for two forces: the unfolding of the innate expectations of the human infant, and the formative influence of environmental supports in guiding those expectations to maturity. The fact is that humans are born in an extremely immature state relative to other existing primates, and this exposes them much more profoundly to the physical and social environment. Our work has been devoted to a probing, scientific exploration of the textured contexts in which development occurs, with a particular focus on urban contexts and on what circumstances are adequate or deficient to serve a childs basic requirements for security, attention, and encouragement. A challenge we accept in advancing this story is that the perspective, capability, and agency of the child must be brought, accurately and respectfully, into the core of our inquiry. Our goal has been the introduction of a method for integrating children into the realm of the community life and its endless pursuit of democratic ideals.

D EANDRE IS as handsome and inquisitive a thirteen-year-old as you will ever meet. He is the youngest of a half-dozen teenage interns on a research project examining exposure to violence in their Chicago neighborhoods. They meet in the projects offices, on the top floor of a bright new office building with large windows overlooking the Kennedy Expressway, just outside the Loop.

On this summer day in 1997, the group is learning about the Convention on the Rights of the Childadopted eight years earlier by the United Nations General Assembly to recognize children as social, economic, political, civil, and cultural actorsand discussing the relevance of this international human rights treaty to their lives as children growing up in Chicago. The United States has recently signed the treaty, although it has not gone so far as to ratify it. (Indeed, fast-forwarding to 2020, the United States remains the sole UN member not to ratify the Convention.)

Up to this moment, Deandre hasnt had much to say, although his posture and gaze indicate that he is a good listener. Now he appears surprised. You mean these rights apply to me? he interrupts. The whole notion of being endowed with rights seems novel to him. He recalls having to pass a test on the Bill of Rights to move into eighth grade last year, but adds, Nobody said they applied to me.

His reaction is understandable. Americas Founders did not have Deandre, an African American male, in mind when they began drafting the Constitution in 1787. Deandres seventh-grade history teacher apparently had not made the connection for him between our nations founding documents, our legal history, and our modern lives. Passing a multiple-choice test allowed Deandre to progress to the next grade level but left him clueless about his own political rights or worthiness to influence civic life in his own backyard.