Landmarks

Page-list

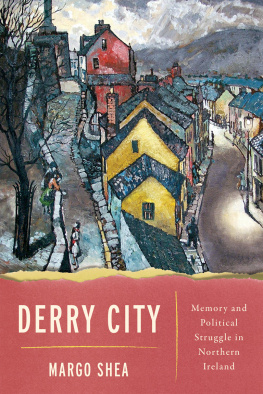

DERRY CITY

DERRY CITY

Memory and Political Struggle

in Northern Ireland

MARGO SHEA

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana

Copyright 2020 by University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

All Rights Reserved

Published in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shea, Margo, 1970- author.

Title: Derry City : memory and political struggle in Northern Ireland / Margo Shea.

Other titles: Memory and political struggle in Northern Ireland

Description: Notre Dame, Indiana : University of Notre Dame Press, [2020] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020007551 (print) | LCCN 2020007552 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780268107932 (hardback) | ISBN 9780268107963 (adobe pdf) |

ISBN 9780268107956 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Derry (Northern Ireland)History20th century. |

Christianity and politicsNorthern IrelandDerry. | CatholicsPolitical activityNorthern IrelandDerry. | Religious toleranceNorthern IrelandDerry. | Nationalism and collective memoryNorthern IrelandDerry. |

Group identityNorthern IrelandDerry.

Classification: LCC DA995.L75 S54 2020 (print) | LCC DA995.L75 (ebook) |

DDC 941.6/21082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007551

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007552

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at

CONTENTS

Two From under the Heel of the Minority:

Challenging Protestant Memory and Power in

Pre-Border Derry, 18961922

Three Against the Wishes of the Inhabitants: Memory

as Mooring in Castaway Derry, 19221945

FIGURES

Figure 6. Image of the Protest Covenant prototype created by the

committee (author photo)

Figure 12. Free Derry drawing (use via Wikimedia Creative Commons license: by Adreanna RobsondeviantART, CC BY 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=950 6090)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book had its beginnings in another book. I first read Seamus Deanes Reading in the Dark in 1998, while on vacation in New Mexico with Britt Anderson, who has the gift and talent of making space for seemingly disparate things. Having spent a summer in Fermanagh many years earlier with American Field Service (AFS) and its affiliate organization Intercultural Educational Programmes (IEP), I was compelled to go to Derry after reading Deane. I was fortunate to be offered a visiting fellowship at Magee College of the University of Ulster. That first sojourn in Derry was a formative one, and it led me eventually to pursue this project on memory and cultural nationalism in Derry City.

I remain appreciative of the work that my academic mentors did to support the original project, from which this current work eventually emerged. David Glassberg, Dermot Quinn, Max Page, and James Young encouraged the project and made it better through their questions, critiques, and suggestions. I am particularly grateful to Dermot Quinn, who helped me get to Derry in the first place, and then guided, encouraged, and challenged me as I tried to learn about and understand Derrys history as an outsider. I am profoundly grateful to the reviewers who offered constructive critique, suggested new avenues of inquiry, and pointed out the strengths and the flaws of manuscript drafts. Special appreciation is due to Eli Bortz at University of Notre Dame Press and to the production team.

Thanks go to many who have read chapters, discussed the work over the years, and contributed in innumerable ways to the arc of ideas included herein, including John Fahey, Elizabeth Cahn, Bryonie Reid, Simon Jolivet, Jon Olsen, Andrew Dausch, Denise Meringolo, Cathy Stanton, Cheryl Harned, Billy Scampton, Richard Wilkie, Jennifer Heuer, Kate Preissler, Andrew Darien, Anna Sheftel, Stacey Zembrzycki, Marla Miller, and the late Diana Colbert. Holly White shared in this Derry story from the outset and has been a valued fellow traveler through life and academe. Bruce Laurie was a formative influence on my history education, and Ira Harkavy instilled in me a sense that scholarship should matter, which has always guided my public history work in Derry. The late Eric Schneider mentored and supported me, introduced me to E. P. Thompson, taught me the power of discipline, and championed my growth from the earliest days of my undergraduate career until his death in 2017. I only hope that his intellectual legacy is visible in these pages.

My colleagues at Salem State have been extremely supportive, and Alex Kyrou, Annette Chapman-Adisho, Brad Austin, Gayle Fisher, Dane Morrison, and Michele Louro have read chapters, participated in writing groups, and provided practical support, encouragement, and advice. Erik Jensen has done all of this and more as officemate, confidante, and ally in all things. A grant from Salem States School of Graduate Studies Scholarship Support Grant Program supported a research trip to Derry. I am grateful to the Salem State University History Department and the Center for Research and Creative Activities for supporting my attendance at conferences so that I could present work and gain valuable feedback.

Many people in Northern Ireland supported this project by offering direction, granting access to archives, agreeing to be interviewed, and suggesting sources and resources. I am grateful to have had a place at the Academy for Irish Cultural Heritages at Magee College of the University of Ulster as a practical and logistical site of operations during the early days of this project. I would like to thank Dr. Billy Kelly, formerly of the University of Ulster, for leading me towards the questions that needed to be asked and teaching me to read between the lines in seeking their answers. Phil Cunninghams work introduced me to a Derry rarely seen in the official sources, and the late Bishop Edward Dalys and Bernard Cannings work illuminated previously opaque avenues of research. Special thanks also go to Louis Childs of the University of Ulster Magee Campus Library; Linda Ming, Jane Nichols, and other reference staff at the Derry Central Library; staff at the Linenhall Librarys Northern Ireland Political Collection; the Heritage and Museum Service of Derry City Councils archives staff; staff at the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland; and Adrian Kerr and John Kelly of the Museum of Free Derry for leading me to and granting me access to useful sources. Local historians Sean McMahon, Michael McGuinness, Ken McCormack, and Brian Mitchell provided extremely useful information, as did Sara Cook, Eamon Deane, and Maureen Hetherington of the Junction, a community relations and peace-building organization. I am especially grateful to the late Bishop Daly and Frank Curran for agreeing to be interviewed, and to Daly for his generosity in working with me in the diocesan archives. Inordinate thanks go to Pamela Kelly and Madeleine McCally for the generosity and knowledge they shared in their interviews.

Paul Gillespie, a columnist for the Irish Times, suggested in 2007 that animating the concept of through-otherness might be the way forward for Northern Ireland. The idea had arrived to him upon recollection of a talk Seamus Heaney had given at the University of Aberdeen in 2001, in which hed invoked the minister-turned-poet W. R. Rodgers. Heaney had observed that Rodgerss life exemplified the triple heritage of Irish, Scottish, and English traditions that compound and complicate the cultural and political life of contemporary Ulster.