THE SPY GAME

INTERNATIONAL AND

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE

Published in 2017 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2017 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2017 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Executive Director, Core Editorial

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Lionel Pender: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Bruce Donnola: Photo Researcher

Introduction and conclusion by Michael Ray.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pender, Lionel.

Title: The spy game : international and military intelligence / Edited by Lionel Pender.

Description: New York, NY : Britannica Educational Publishing, 2017. | Series: Law enforcement and intelligence gathering | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016020889 | ISBN 9781508103592 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Intelligence service--Juvenile literature. | Espionage--Juvenile literature. | Spies--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC JF1525.I6 S79 2017 | DDC 327.12--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016020889

Photo credits : , interior pages (background) stefano carniccio/Shutterstock.com

CONTENTS

L eaders of all kinds seek to obtain intelligence, or secret information, to achieve an advantage over their opponents. Heads of government, presidents of companies, and even managers of sports teams try to acquire information that would give them insight into the intentions or weaknesses of their adversaries. In this book, we will examine the development of intelligence gathering as a discipline and the growth of national intelligence agencies around the world.

Any discussion of spies naturally conjures images of James Bond and clandestine operations conducted with high-tech gadgets. Field agents certainly do have a role in the gathering of intelligence, although few would likely aspire to a job as action-packed as 007s. The life of a clandestine agent is fraught with danger, as evidenced by the Memorial Wall at the original headquarters building of the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Langley, Virginia. The wall is covered with scores of stars, one for each agent who lost his or her life in the line of duty. While many of the agents names are listed in a book of honor that accompanies the memorial, some names remain secret to this day.

Risk has always accompanied the job of the field agent. During the American Revolution, American officer Nathan Hale was executed by the British as a spy, while British officer John Andr was executed by the Americans. The inherent danger of intelligence gathering prompted countries and their militaries to develop strategies thatin theorywould minimize the possibility of harm to their own assets while maintaining a watchful eye on their enemies. Technology has come to play an enormous role in these efforts. The Space Race saw the United States and the Soviet Union jockeying for orbital advantage, with satellites offering a real-time glimpse of events on the ground. No longer would analysts be forced to wait for sensitive sites to be photographed by spies on the ground or glimpsed by reconnaissance aircrafta camera thousands of miles above Earth could deliver crisp images of actions as they transpired.

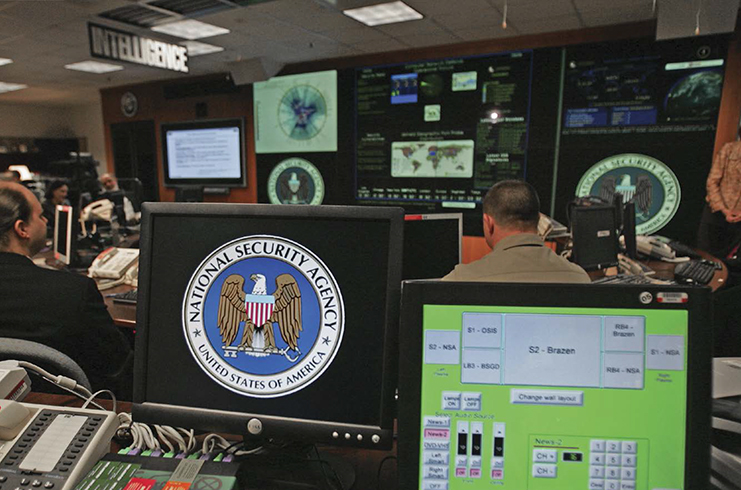

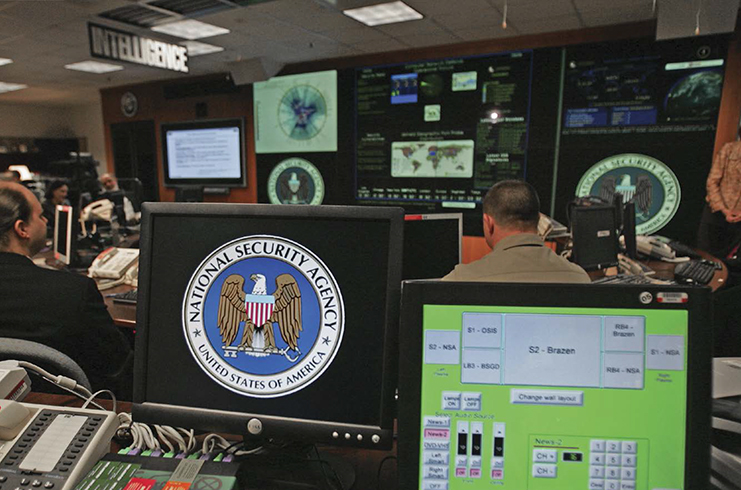

While the thought of spies often brings to mind the action-packed scenes of Hollywood movies, in reality intelligence gathering often occurs behind closed doors in agency headquarters.

This sort of tactical data can be invaluable, but even the best raw intelligence is worthless without informed analysis. A pair of US Army Signal Corps radar operators detected the first wave of Japanese bombers approaching Pearl Harbor nearly an hour before the attack began on the morning of December 7, 1941. They notified their information center, but the officer on duty disregarded the warning, believing the planes to be a squadron of American bombers approaching from the mainland. The proliferation of computer technology has certainly aided in the handling and analysis of intelligence, with the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) going so far as to propose an initiative titled Total Information Awareness. The goal of the program was to create an all-encompassing surveillance network, with computers performing threat analysis on all electronic communication and digital traffic. The program was officially discontinued after a flurry of media criticism, but many elements of it were preserved by the National Security Agency (NSA). For a time the NSA, jokingly referred to as No Such Agency because of the intense secrecy surrounding its operations, reportedly intercepted billions of emails, data transmissions, and phone records every day. With this staggering volume of data streaming in around the clock, one is forced to consider if there could be such a thing as too much intelligence.

I ntelligence, in government and military operations, is evaluated information about the strength, activities, and probable courses of action of foreign countries or non-state actors that are usuallyalthough not alwaysenemies. The term is also used to refer to the collection, analysis, and distribution of such information and also to secret intervention in the political affairs of other countries, an activity commonly known as covert action. Intelligence is an important component of national power and an essential element in decision making regarding national security, defense, and foreign policies.

Intelligence is conducted on three levels: strategic (sometimes called national), tactical, and counterintelligence. The broadest of these levels is strategic intelligence. Strategic intelligence includes information about what foreign countries have the capability to do and their general intentions. Tactical intelligence (which is sometimes called operational or combat intelligence) is information required by military field commanders. Because of the destructive power of modern weapons, the decision making of world leaders must often consider information derived from tactical as well as strategic intelligence. Military commanders, too, may often need multiple levels of intelligence. As a result, the distinction between these two types of intelligence may be diminishing.

Counterintelligence is intelligence aimed at protecting a countrys intelligence operations and keeping them secret. Its purpose is to prevent spies or other foreign agents from infiltrating the countrys government, military, or intelligence agencies. Counterintelligence is also concerned with protecting advanced technology, preventing terrorism, and combating international drug trafficking. Counterintelligence operations sometimes produce positive intelligence, including information about other countries intelligence-gathering tools and techniques and about the kinds of intelligence other countries are seeking. Counterintelligence sometimes involves the use of moles, or double agents, to manipulate an adversarys intelligence services. In authoritarian states (where a single power holder, such as a dictator or military group, controls all aspects of the government), counterintelligence commonly entails the surveillance of key elites and the repression of dissent.