PM P RESS PAMPHLET SERIES

| 0001: | BECOMING THE MEDIA: A CRITICAL HISTORY OF CLAMOR MAGAZINE

By Jen Angel |

| 0002: | DARING TO STRUGGLE, FAILING TO WIN: THE RED ARMY FACTIONS 1977 CAMPAIGN OF DESPERATION

By J. Smith and Andr Moncourt |

| 0003: | MOVE INTO THE LIGHT: POSTSCRIPT TO A TURBULENT 2007

By The Turbulence Collective |

| 0004: | THE PRISON-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX AND THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

By Eve Goldberg and Linda Evans |

| 0005: | ABOLISH RESTAURANTS: A WORKERS CRITIQUE OF THE FOOD SERVICE INDUSTRY

By Prole |

| 0006: | SING FOR YOUR SUPPER: A DIY GUIDE TO PLAYING MUSIC, WRITING SONGS, AND

BOOKING YOUR OWN GIGS

By David Rovics |

| 0007: | PRISON ROUND TRIP

By Klaus Viehmann |

| 0008: | SELF-DEFENSE FOR RADICALS: A TO Z GUIDE FOR SUBVERSIVE STRUGGLE

By Mickey Z. |

| 0009: | SOLIDARITY UNIONISM AT STARBUCKS

By Staughton Lynd and Daniel Gross |

| 0010: | COINTELSHOW: A PATRIOT ACT

By L.M. Bogad |

| 0011: | ORGANIZING COOLS THE PLANET: TOOLS AND REFLECTIONS TO NAVIGATE THE CLIMATE CRISIS

By Hilary Moore and Joshua Kahn Russell |

| 0012: | VENCEREMOS: VICTOR JARA AND THE NEW CHILEAN SONG MOVEMENT

By Gabriel San Romn |

PM Press Pamphlet Series No. 0012

Venceremos: Vctor Jara and the New Chilean Song Movement

Gabriel San Romn

ISBN: 978-1-60486-957-6

Copyright 2014

This edition copyright PM Press

All rights reserved

Layout by Jonathan Rowland

Cover illustration by Carla Zarate Suarez

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in Oakland, CA, on recycled paper with soy ink.

Contents

To my father Alfonso, my mother Graciela, and my brother Javier and sister Yvette. To my nephew crew: Alex, Adrian, and Marcos. And for Irene, my love.

FOREWORD

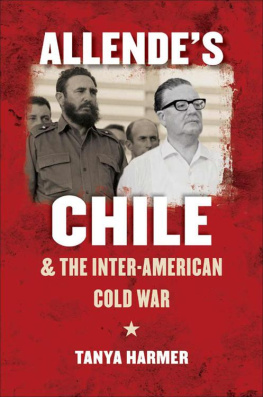

T HE POWER AND RESILIENCY OF ARTISTS COMMITTED TO PROFOUND SOCIAL change resounds over time and across natural and human-created borders. This pamphlet is a testament to how the musical expressions of that commitment can bridge decades and span a hemisphere. Gabriel San Romn begins by describing how his encounter in North America with Chilean music created several decades previous, in particular that of singer-songwriter Vctor Jara, led to his engagement with this musical culture that now offers this welcome recounting of musics fundamental role in Chile throughout the 1960s and into the 70s. The upwelling of organization and confidence in the ability to transform ones world by the long dispossessed continually grew within Chile during this time-frame. By all accounts it was a tumultuous period when people could feel Chiles social pulse quicken, a feeling that the genie could not be so easily returned back into its bottle, that both the majority population and the ruling elite were aroused into action and some kind of alteration of the nations assemblage had to occur: past socioeconomic and political arrangements felt like a holding pattern, an airplane awaiting orders either to climb to new elevations or abort the journey altogether. The answer was confirmed in newspapers around the world on September 12, 1973, in the smiling faces of now-deceased U.S. president Richard Nixon and living but still unjailed Henry Kissinger photographed around a table in the White House. Their grinning happiness that morning signaled the triumph of sustained and crucial support by various U.S. government agencies to empower and secure the privileges of Chiles ruling class and its military guardians. Operation Condor, a coordinated campaign by North and South American militaries and so-called security agencies, ramped up already existing repression into a multiyear slaughter of any politically progressive people and ideas in the southern half of South America. The coming gush of profits for multinational corporations and local capitalists would be marketed as The Chilean Miracle; for those described in these pages, the era became known as El Apagn Cultural, the Cultural Blackout.

Just as the upheavals in Central America in the 1980s brought some of the music of that region to the attention of international audiences, so the exile of Chilean New Song groups Inti-Illimani and Quilapayn and continued solidarity with the Chilean resistance introduced Andean musics to new audiences. Tragically, Vctor Jara was not one of those musical ambassadors. But his recordings were released and circulated among both Latin and Anglo-Americans and Europeans and actually gained greater popularity than during his lifetime. At the same time, his compatriots in Chile had to hide their LPs, and the government sought the master tapes of his sessions in an attempt to permanently erase his presence from the planet.

What would be called the Nueva Cancin (New Song) movement drew from the earlier Nueva Ola (New Wave) in Chile in the 1960s that popularized non-Chilean instruments and music from the altiplano, the Andean highlands of neighboring Bolivia and Peru. Although interpreted in a new urban, city-based style, the sikus (also called zampoas, pan pipes), kena (high-pitched notched vertical flute), and charango (small ten-stringed guitar) became immediately recognizable icons of neighboring cultures that came to represent a regional and, later with Nueva Cancin, even a continental source of identity and pride. Vctor Jara was eclectic in forming his musical style, drawing from a variety of musical influences. He was a preeminent member of the Nueva Cancin movement, using altiplano instruments, especially the kena, and often donning the Andean poncho that became the uniform of Quilapayn. But he also used Chiles own guitarrn double-stringed guitar, as on his classic Plegaria a un Labrador (Prayer to a Worker); he recorded his translation of two U.S. folk protest songs, Little Boxes and If I Had a Hammer; and he recorded a couple of his own compositions with the Santiago-based rock-pop band Los Blops. The forceful macho assertion in the massed voices and heroic bearded male hero found in Quilapayn and others found a more well-rounded socially engaged male figure in Vctor, secure in both dynamic denunciation of injustice and in expression of tenderness and love: Deja la Vida Volar remains an enduring romantic love song today.

The all-too-brief three years of the Popular Unity coalition that elected the Socialist Partys Salvador Allende and others into high government positions made great strides that echo today in the ferment across Latin America that also pushes for a more just and equitable society. The pink tide, or better put Latin American Spring, draws inspiration from the audacious time in Chilean history when exploitative structures, both political-economic and sociocultural, were challenged and chipped away from below and above. From Venezuela to Bolivia to Ecuador to Uruguay, current social movements combine organization and development of new relations in communities and workspaces with a regional and national electoral strategy that neutralizes repression and garners support from governmental structures. Popular Unity suffered from moving Chilean society forward, with land reform, community organizing, workplace improvements, and a host of planned initiatives, without simultaneously preparing to physically defend these gains when necessary and working to neutralize a praetorian guard whose officers were indoctrinated in the notorious School of the Americas in the United States. The cautionary lessons from Chile remain prescient today. Venezuelas president Hugo Chvez often stated, We are peaceful, but we are armed. And Ecuador recently expelled both the U.S. Air Force base and USAID from the country.

Next page