Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Teaching Critically About Lewis and Clark

Challenging Dominant Narratives in K12 Curriculum

Alison Schmitke

Leilani Sabzalian

Jeff Edmundson

Published by Teachers College Press, 1234 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027

Copyright 2020 by Teachers College, Columbia University

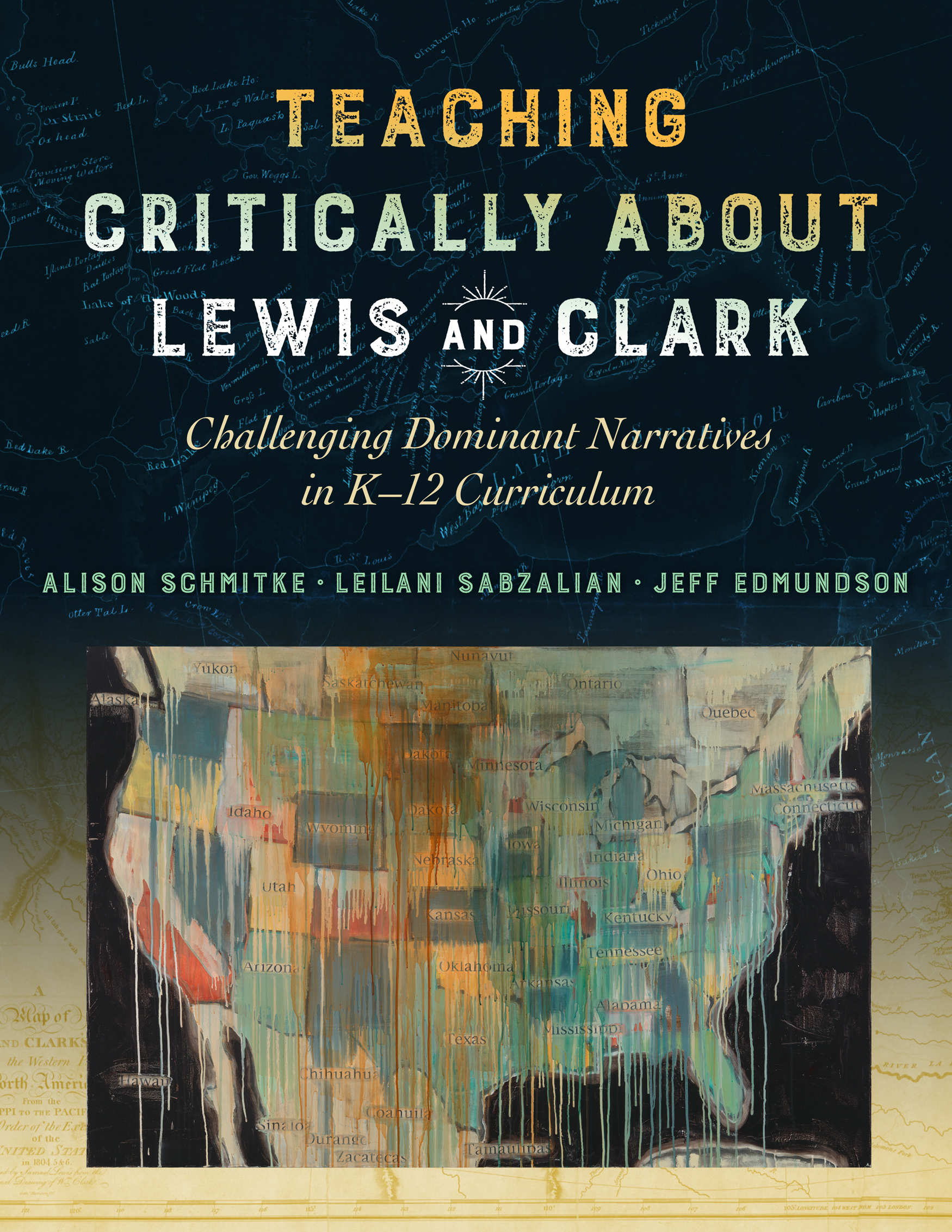

Cover painting: Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, State Names, 2000, oil, collage and mixed media on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Elizabeth Ann Dugan and museum purchase. Map of Lewis and Clarks expedition courtesy of the Library of Congress.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher. For reprint permission and other subsidiary rights requests, please contact Teachers College Press, Rights Dept.: tcpressrights@tc.columbia.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available at loc.gov

ISBN 978-0-8077-6370-4 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-8077-6371-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-8077-7848-7 (ebook)

Printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

We call upon all those who have lived on this Earth

Our ancestors and our friends,

Who dreamed the best for future generations,

And upon whose lives our lives are built,

And with thanksgiving, we call upon them to

Teach us and show us the way.

This blessing was read by Chinook Nation Chairman Gary Johnson on November 18, 2005, at the dedication of the Confluence Project site at Cape Disappointment. This was 200 years to the day from the arrival of the Corps of Discovery.

Contents

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to our families for supporting us, and to all who contributed to this project. Thank you to the teachers willing to teach drafts of the lesson plans and provide significant feedbackBrittany Dorris, Jenny Henke, Rachel Hsieh, Grace Groom, Tristan Moore, Heidi Sawitzke, and Julia Von Holt. We thank Greg Archuleta and Chris Remple, both members of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, for sharing their expertise about native plants for the trading card activity. We thank Rachel Cushman (Chinook) for sharing expertise about Canoe Journeys and the Chinook Indian Nation, and for her story We Dont Need Those Anymore. We thank Courtney Yilik and Colin Fogarty at the Confluence Project. We thank Stephanie Wood and Dick Basch (Clatsop, Nehalem) with Honoring Tribal Legacies. We extend our gratitude to Rene Watson. Thank you also to Bill Bigelow and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca with Rethinking Schools and the Zinn Education Project. Finally, thank you to Ashley Cordes (Coquille), Lydia Giomi, Jeanne Hall, Katie Jewel, Alex Pratt, Nellie Schmitke-Rosiek, Donovan Wilson, Randy Town, and Anna Tsoi.

CHAPTER 1

Beyond Adventure

One and a half billion acres. This is the number calculated by Claudio Saunt (Onion & Saunt, 2014) when he developed an interactive map calculating the exact acreage the U.S. government has seized from the Indigenous peoples of North America since 1776. To be more precise, the exact number would be 1,510,677,343 acres. That is almost two million square miles. If you were to calculate the rate at which the U.S. government dispossessed Indigenous people of their lands, it would be at a rate of two square miles per hour (Spirling, 2011, p. 1).

These billions of acres of Indigenous land were seized by treaty and executive order, whittling away the vast stretch of Indian Country that encompassed all of North America to a mere 56.2 million acres (Bureau of Indian Affairs, 2017). Though millions of acres may appear a vast tract of land, it is less than 90,000 square miles, and hardly sufficient when considering it is divided among the 326 Indian land areas in the United States administered as federal Indian reservations. For example, Likely Rancheria, operated by the Pit River Tribe in California, is a 1.32 acre parcel that is just large enough for the cemetery. Further, the 326 land areas do not account for the nearly 600 federally recognized tribal nations in the United States, leaving many of those nations not with small patches of land, but landless. Moreover, those precious few acres of land must continually be defended by Indigenous people and nations who still face encroachment on their lands even today. The courage and resistance of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, Kanaka Maoli, Winnemem Wintu, Osage Nation, the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, Lummi Nation, and the Standing Rock Sioux, among other nations and intertribal organizations, demonstrate how the theft of Indigenous lands and resources creates present-day battlegrounds for Native nations. (For further reading and teaching ideas, refer to Teacher Resource 1: Native Lands Under Siege and Secondary Lesson Plan 5: Standing Rock and the Larger Story.)

This story of dispossessionand resistancehas roots that are rarely examined. While most students have heard something about Manifest Destiny, very few have heard of the medieval white supremacist Doctrine of Discovery and the U.S. Supreme Court cases that enshrined that belief system into U.S. laws. Additionally, rarely do students learn that the instructions given to the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery to document and report their observations was part of a strategy to establish land claims justified by the Doctrine of Discovery. As Eastern Shawnee legal scholar Robert Miller (2008) states,

When European and Americans planted their national flags and religious symbols in these newly discovered lands, they were not just thanking Providence for a safe voyage. Instead, they were undertaking the well-organized legal procedures and rituals of Discovery designed to demonstrate their countrys legal claim over the new discovered lands and peoples. (p. 1)

Dominant narratives are reproduced as official knowledge in schools, particularly through the conventional ways the Corps of Discovery is framed in social studies textbooks. As we will discuss in , the conventional ways Lewis and Clark are framed are embedded with colonial logics and reproduce Indigenous erasure.

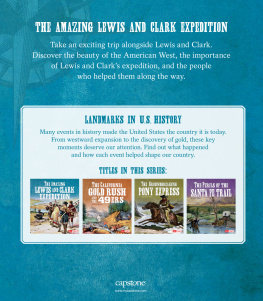

In textbooks, the Corps of Discovery is presented as a tidy narrative of exploration and science. For example, in The United States: Making a New Nation (Harcourt Social Studies) (Berson, Howard, & Salinas, 2012), an elementary textbook, students are presented the following excerpt:

Little was known about the land in the Louisiana Purchase. President Jefferson wanted to learn what resources the area had. Jefferson chose a friend and army officer named Meriwether Lewis to plan and lead the expedition. Lewis asked his friend and fellow army officer William Clark to help. Clark was responsible for keeping records and making maps. Lewis and Clark drew many maps showing mountain passes and major rivers. They brought back seeds, plants, and even animals. President Jefferson was proud of their success. (p. 430431)