Peter Charles Hoffer - Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery

Here you can read online Peter Charles Hoffer - Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Peter Charles Hoffer: author's other books

Who wrote Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS

Ithaca and London

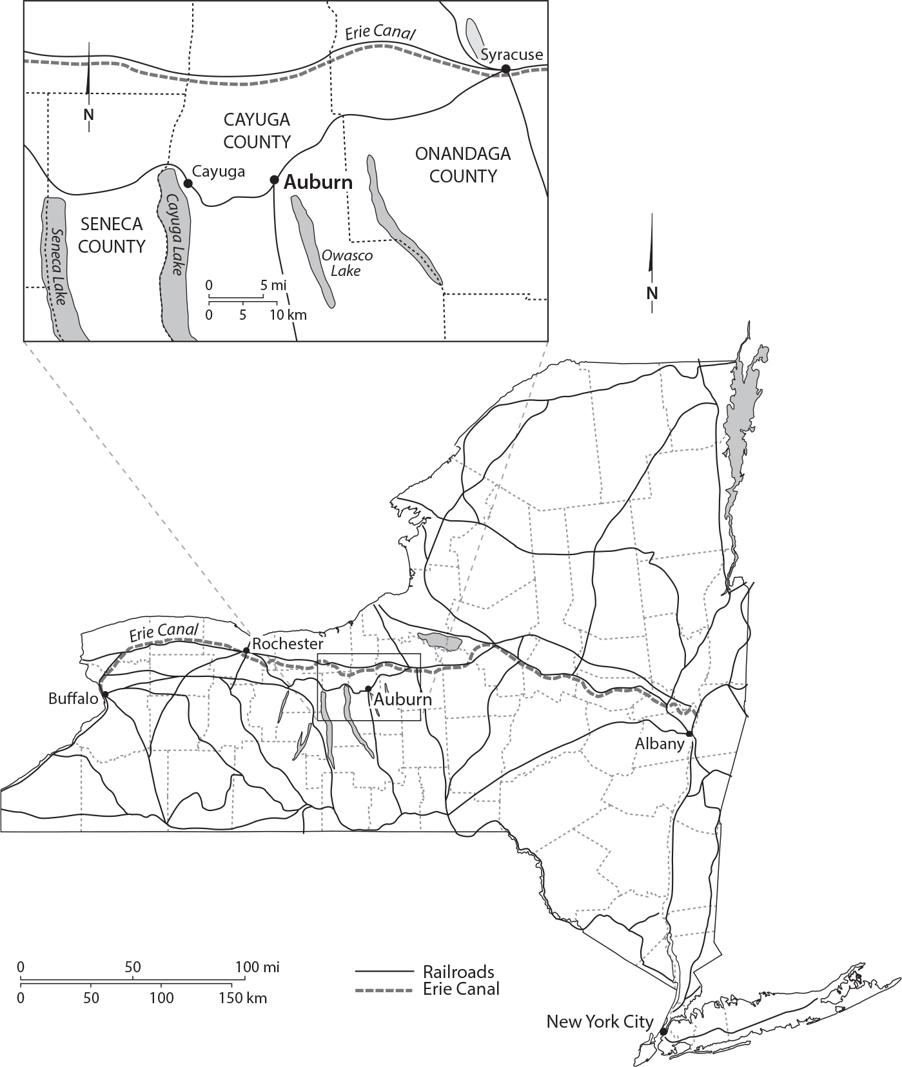

Sewards legal world, ca 1855. Map by Bill Nelson.

The William Henry Seward (18011872) of the history books is an antebellum and Civil War politician who almost won the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. He is the secretary of state who enabled the purchase of Alaska from tsarist Russia. Not so well known is that Seward was one of the eras most successful litigators, anointed the king of the patent law bar by one newspaper. Even more important, though largely ignored, is Sewards effort to frame a jurisprudence based on relational rights in a democratic society. These rights were communal and reciprocal, what everyone owed to every other member of the community. Though limited by the Victorian mores and the racialist presumptions of the day, relational rights was a platform for the end of slavery. Slave law was the antithesis of this liberal jurisprudence, for in the legal regime of the peculiar institution masters owed nothing to their bondmen and women, while those enslaved owed life and labor to their masters.

Seward, decried in his time variously as an ambitious trimmer, a rabid abolitionist, and a tool of political operator Thurlow Weed, was not wholly any of those. Aligning his legal practice with his politics reveals a man who wanted more and better law through reasoned and progressive politics. Neither conservative nor radical, Sewards relational jurisprudence infused his arguments in court, his ideas of good laws, his public orations, his speeches in Congress, and his view of political parties. He believed that public law should evolve toward freedom of enterprise and equality of persons before the law and that the Constitution incorporated a standard of relational duty and dignity. His union, as he said in his most famous public address, was a democracy of property and persons, a bond created by a fair approximation of universal education and operating by means of universal suffrage, sadly, a vision that he would not live to see fulfilled and even more sadly, one that he did not fully understand, for he could not and would not see everyone as fitting his ideal of equality.

My assumption here, as in my other works, is that a lifetime spent as a lawyer influences how one responds to the challenges of everyday life, including those of public life. Even when he entered the highest realms of national politics, Seward remained a country lawyer at heart. His habits of mind, his jurisprudential instincts, if one can call them such, arose out of his practice of law in upstate New York. He professed to hate the day-to-day strife of litigation, but he loved winning in the cockpit of the courtroom.

Once upon a time in the first half of the nineteenth century, the vast majority of legal practitioners in America were country lawyers. As the country lawyer began to vanish from the landscape, Justice William O. Douglas, who had briefly opened a law practice in his Yakima, Washington, hometown, told the American Bar Association that the country lawyer would always be an integral part of the community in which he lived, for his position in town and country exacted responsibilities. Soon to be Justice Louis D. Brandeis was even more effusive in his praise. The country lawyer secured breadth of view largely through wide professional experience. Being a general practitioner, he was brought into contact with all phases of contemporary life The relative smallness of the communities tended to make his practice diversified not only in the character of matters dealt with, but also in the character or standing of his clients. For the same lawyer was apt to serve at one time or another both rich and poor, both employer and employee. Furthermorenearly every lawyer of ability took some part in political life.

Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson had been a country lawyer. He recalled what the jobs responsibilities were. The county-seat lawyer, counsellor to railroads and to Negroes, to bankers and to poor whites always gave to each the best there was in him-and was willing to admit that his best was good. Jackson concluded that the country lawyer has been an American institution Such a man understands the structure of society and how its groups interlock and interact, because he lives in a community so small that he can keep it all in view. The country lawyer was the person to whom one went with problems, who would listen and adviseat no cost (at first). He was trusted. He settled disputes among neighbors long before the profession of mediator appeared. He did not specialize, nor did he pick and choose clients. He rarely declined service to worthy ones because of inability to pay. Once enlisted for a client, he took his obligation seriously. Douglas agreed: country lawyers very often are closer to the hearts and dreams of America than the prominent big-name lawyers.

The country lawyer was not easily bluffed or confused. He saw issues and people for what they were. His adoption of the country manner was as much a pose as the antebellum urban gentrys adoption of European sophistication. A country lawyer himself, Illinoiss Abraham Lincolns penchant for telling stories during legal consultation or in court was a prime example of this calculated behavior. As a practicing lawyer, traveling from one county seat to another, Lincoln discovered the effectiveness, power, and usefulness of the well-placed anecdote. Though hardly in Lincolns league as a raconteur, New Yorks William Henry Seward was also a superb master of ceremonies and an inveterate storyteller, enjoying (and later recording in detail) his conversations with anyone who came to his door in Auburn.

It may be too easy to oversimplify the country lawyer as if there were but one type. The use of the term should not obscure the variety in country law practices and practitioners. Some country lawyers did not aspire to more than their rural practices and their local lives. Some were unsuccessful in practice and uprooted themselves over and over. Others eagerly left the countryside and journeyed to the city and (sometimes) fame. But their traits were general ones, and they would have recognized one another in town, in the courtroom, and on the country roads they once traveled. True, many of the most prominent lawyers of the years before the Civil War were determined not to be country lawyers. One thinks of the early national New York bars stars like James Duane, Alexander Hamilton, and Aaron Burr, none of whom can be called country lawyers. Or Daniel Webster and William Pinkney, who began their careers in the country and left as soon as they could to live and work in Boston and Baltimore, respectively.

The practice of law in the small towns and rural areas that dominated the countryside in the years before the Civil War had both an elevating and humbling character. Law was a profession, subject to codes of conduct, requiring specialized study and admission to local and state bars based on examinations. For the most part, lawyers and judges enjoyed elite status in antebellum middle-class America. At the same time, lawyering was a competitive, exhausting, and often frustrating occupation in a world of rapid change. Losing a case was a humbling experience. As Seward wrote during his battle to save Henry Wyatt from the gallows, in this court I am fighting a battle in which I ask no sympathy or support. He got none, and his client was convicted.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery»

Look at similar books to Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sewards Law: Country Lawyering, Relational Rights, and Slavery and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.