First published 1980 in Great Britain by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

Gainsborough House, Gainsborough Road, London, E 11 1RS, England

Reprinted 2005 by Frank Cass

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

Frank Cass is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

Copyright 1980 Barry Rubin

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Rubin, Barry

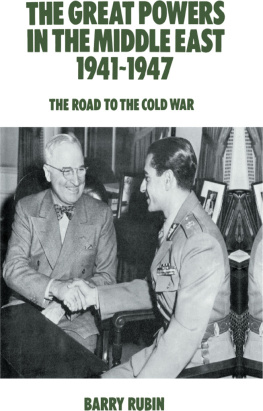

The Great Powers in the Middle East, 1941-1947.

1. Near East Foreign relations

2. World War, 1939-1945 Diplomatic history

3. World War, 1939-1945 Near East

I. Title

327.56 DS63 80-50000

ISBN 0-7146-3141-8

ISBN 9781135168773 (ebk)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Frank Cass and Company Limited.

Printed and bound by Antony Rowe Ltd, Eastbourne Transferred to digital print on demand, 2005

Cover photograph of President Truman and the Shah of Iran by permission of US National Archives.

Jacket design by Andy Jones

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Jules Davids, of Georgetown University, whose detailed, constructive criticism has provided a worthy model of the historical craft. I am also grateful to the Institute of Contemporary History and to Walter Laqueur for the support which enabled me to carry out research in London. Comparison of British and American sources once again reinforced the importance of multi-archival work in diplomatic history.

Among the others who provided assistance, the work of the staffs of the National Archives, particularly John Taylor, and of the Public Records Office, was constantly above and beyond the call of duty. John Davies shared with me his intimate knowledge of the Foreign Office archives; Steven Zipperstein and Dorothy Brown provided needed encouragement. Most of all, I wish to thank Kathleen Rubin, whose assistance and advice have always been the most important thing in my life.

The period of time between 1941 and 1947, wrote Dean Acheson in his memoirs,

was one of great obscurity to those who lived through it. Not only was the future clouded. We all had far more than the familiar difficulty of determining the capabilities and intentions of those who inhabit the planet with us. The significance of events was shrouded in ambiguity. We groped after interpretations of them, sometimes reversed lines of action based on earlier views, and hesitated long before grasping what now seems obvious.*

The objective of this study is to reconstruct the difficulty faced by American and British policy-makers in determining the capabilities and intentions of their two main wartime allies with regard to the Middle East. Specifically, it seeks to explore the role of great power relations in the Middle East in the breakdown of the wartime alliance and in the origins of the Cold War.

From this central question flow several other concerns. How seriously, in the policy-making process, did the State Department and the Roosevelt White House take their anti-colonial and Atlantic Charter expressions of opinion? Did the war-time US government attempt, in the Middle East, to build peace-time Allied relations on a foundation of friendship between the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union? What role did the small nations of the region play in influencing the inter-relations of the great powers?

A number of other controversial issues are considered. How much did Russian behavior influence American steps toward the Cold War? Did American policy-makers fail to consider, as some historians charge, what might be legitimate Russian defensive and strategic interests? Did the United States and Britain, as Russian historians have claimed, gang up on the Soviet Union? Did the United States, as British sources have claimed, encourage Russian aggression through its weakness and naivete? These points are analyzed employing events in the Middle East as a case study or, rather, as several case studies.

Much of the material for this book comes from the records of the United States State Department, the Office of Strategic Services, and the British Foreign Office. Do these documents provide an accurate measurement of the developing perceptions of policy-makers? The answer is that, augmented by other sources, their evidence seems to be reliable. The vast majority of letters, reports, memoranda, orders, and minutes were for internal use. Their authors aimed not at swaying public opinion, but rather sought to explain or argue their personal or collective positions on the questions at hand. They are writing to express the highest level of available information and analysis, as seen through their eyes. In such a context, dissimulation of thought and opinion seems to be minimal.

In contrast, secondary sources and memoirs, particularly those written years after the events, are used with extreme care, for the later developments of the Cold War often seem to inform memoirs of earlier days. Writers and participants, in hindsight, tend to see a greater hostility and fear of Russia on the part of American officials than, the documents indicate, actually existed at the time. Such sources, then, have been used more on issues of fact although even here there are errors, as Trumans memoirs demonstrate rather than as statements of contemporary attitudes and thinking.

Another point of importance is the need to evaluate the relative impact of particular actions and documents. An argument or document might show foresight without escaping from obscurity in its own time. The influence of State Department and OSS materials can be judged, in part, by their authors and intended readers. Beyond this, however, the extent to which the ideas contained in OSS reports or in documents produced by lower-level State Department officials are later found incorporated verbatim into major State Department and Joint Chiefs of Staff documents, makes this task easier.

The British records provide a fascinating perspective on Anglo-American relations in the Middle East as well as a check against the American viewpoint, especially in describing meetings. The minutes of Foreign Office officials, who were extremely interested in evaluating American attitudes toward their policies, are also a good source.

Access to Soviet archives, or even to authoritative internal accounts of Russian thinking, is impossible. Hence, we have tried to always stress that our focus is on what British and US policymakers thought the Russians were doing and planning, based on the evidence available to them.

Another problem is the impingement of outside events on great power relations in the Middle East. Not only must developments in Asia and Europe be kept in mind, but also domestic influences on US foreign policy need be considered. For many of the years under study, and particularly for the 19411945 period, American policy often seemed fragmented, specific problems and areas being dealt with on their own terms. At any rate, reference to these points has also been made, where appropriate.