Copyright 2003 by Irene Quenzler Brown and Richard D. Brown

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2005

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brown, Irene Quenzler.

The hanging of Ephraim Wheeler : a story of rape, incest, and justice in early America / Irene Quenzler Brown, Richard D. Brown.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-674-01020-5 (cloth)

ISBN 0-674-01760-9 (pbk.)

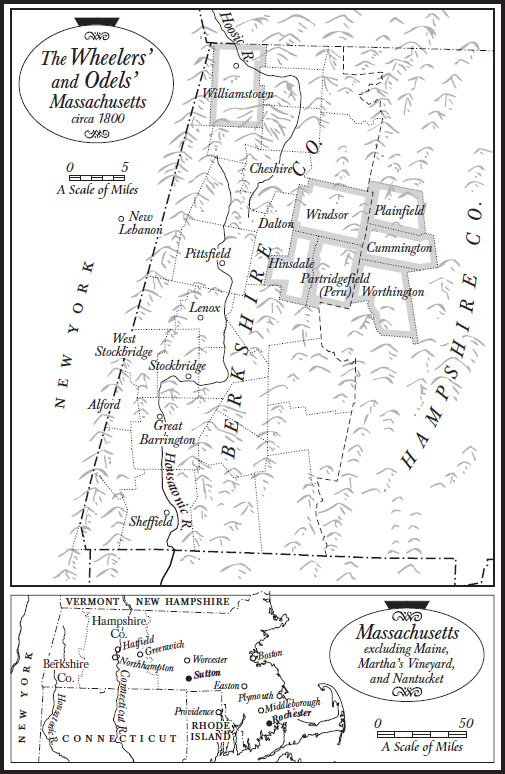

1. Wheeler, Ephraim. 2. RapeMassachusettsBerkshire CountyHistory19th centuryCase studies. 3. IncestMassachusettsBerkshire CountyHistory 19th centuryCase studies. 4. HangingMassachusettsLenoxHistory19th centuryCase studies. 5. Problem familiesMassachusettsBerkshire County History19th centuryCase studies. 6. Interracial marriageMassachusetts Berkshire CountyHistory19th centuryCase studies. 7. Capital punishment MassachusettsBerkshire CountyHistory19th centuryCase studies. 8. Berkshire County (Mass.)Social conditions19th century. 9. Berkshire County (Mass.) Social conditions18th century. I. Brown, Richard D. II. Title.

HV6565.M4B76

2003 364.15 364.15'32'097441dc21 2002038266

FOR

JOSIAH AND NICHOLAS

AND THEIR GRANDPARENTS

View of Lenox, 1837

Title page of the Report of the Trial of Ephraim Wheeler, 1805, and James Sullivans handwritten inscription

James Sullivan, 1807

Daniel Dewey, ca. 1810

Theodore Sedgwick, 1808

Sedgwick homestead

Wheeler family petition

Idle Prentice Executed at Tyburn, 1747

Massachusetts State Prison, 1806

Caleb Strong, 1807

The Reverend Samuel Shepard, 1830s

Lenox Meetinghouse

Hanging at Castine, Maine, 1811

Catharine Maria Sedgwick, 1832

T he Reverend Samuel Shepards words on the rainy afternoon of February 20, 1806, had been aimed at him: EPHRAIM WHEELER Your heaven or hell may hang suspended on the present moment . Look back on a life, all covered with pollution! Fly to the ark of safety. Now the moment for his execution had arrived. The authorities had ordered that he be launched into eternity within the hour, to dwell in hellfire or heaven forever.

The country folk of Berkshire County could only imagine Ephraim Wheelers thoughts during the jolting, chain-clanking cart ride down the hill and along the muddy road as he passed among the

In his gloom, Wheelers only glimmer of hope was that the petitions asking to spare his life, petitions that he and over one hundred others had signed and sent to the governor, might yet be granted.

As he rode along looking out at the sea of upturned, mostly silent faces, he might have thought back to the bright June day eight months earlier, when he had been arrested on the charge of raping his thirteen-year-old daughter, Betsy. At the time, his arrest had taken him by surprise and a trial seemed unlikely. But when Betsy, backed by his wife, Hannah, accused him before a justice and then stuck to her story throughout the summer, the Berkshire grand jury indicted him. When Wheeler came to trial in September, he knew he was in

Wheeler had hoped, perhaps even expected, that this panel would acquit him. His lawyers might have assured him that the odds were in his favor, since jurymen rarely convicted defendants of rape, especially when those charged were white Yankees like themselves. Jurors preferred to find prisoners guilty of the lesser charges of attempted rape or lewd and lascivious behavior, crimes that at most carried penalties of a year or two in prison and sometimes only an hour on the pillory plus a fine. But Wheelers accuser was not just any young serving woman; she was his own daughter. That was why the Lenox courthouse had overflowed with hundreds of spectators, and that was why a nearby printer had hired a man to attend the trial to compile an exact report for publication and sale. The printer believed there was a market for Wheelers life story. The charge of incestuous rape was shocking, and made Wheeler the subject of press coverage all over New England and even as far away as Richmond, Virginia.

After the verdict was brought in and the sentence pronounced, Wheeler had gone back to jail, where he had plenty of time to nurse his sense of injury. From his Narrative we know that above all he blamed his wife and his daughter for putting his life in jeopardy. Hannah, his wife of fourteen years, had never been the love of his life. But she had borne him five children, and she was a good worker and a frugal housewife. Her family, some of whom were recognizably Even if the governor were to commute his sentence, Wheeler knew he would be locked up for the next twenty-five years at least. His wife would triumph, and he was as good as dead.

In fact, however, neither Wheeler nor the thousands who watched him on his ride to the gallows as yet knew his fate. Wheelers attorneys had drafted a petition for him to mark (he could not write his name), and they had also sent their own carefully argued pardon petition to the governor. In addition, over one hundred men, including over seventy from Wheelers own town of Windsor, had petitioned to save his life. Most of them believed that rape should not be punished by death. Two Congregational pastors, the county sheriff, and leading Federalists and Republicans had all signed to save him. They knew, as did Wheelers attorneys, that just four years earlier, Governor Caleb Strong had pardoned a black man from India who had been sentenced to die after raping a white girl.

During the five months between Wheelers sentencing and the February date for his execution, no pardon had come, and Wheelers desperation had mounted. Yet he continued to hope right up until the last minute. It was generally understood that in order to dramatize the power of the state to punish, the sheriff was sometimes directed to wait until he had placed the rope around the subjects neck before proclaiming a last-minute pardon. Twenty years before, when Berkshire leaders of the Shays Rebellion stood convicted of treason, the state had enacted precisely this drama at the Lenox gallows. And

This is a book about Americans who were caught up in a shocking criminal case two hundred years ago. Confronted with a capital crime, they tried to find the path of justice. Their statutes and procedures were clear enough: but in addition they relied on discretion and judgment. Victims had to decide whether to complain and testify. Witnesses had to choose their words. And court professionals and public officials had to fulfill their prescribed duties under the scrutiny of their peers and the public. Indeed the stakes were high for participants of all ranks, living as they did in a small society under their neighbors surveillance and acting without the confidentiality supplied by impersonal bureaucracy or the privacy that accompanies metropolitan life.