This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2018 by Jeffrey B. Lilley

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-03242-3 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-253-03244-7 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-03446-5 (MOBI)

ISBN 978-0-253-03243-0 (web PDF)

ISBN 978-0-253-03445-8 (ePub)

1 2 3 4 5 23 22 21 20 19 18

For Lynn and Mom. Thank you.

PREFACE

This book was sparked by a desire to explore one of the major events of the twentieth century, the Cold War, and one of the defining moments in my life, the collapse of the Soviet Union. I studied Russian and later lived in Moscow during the years spanning the fall of the Soviet Union and the rise of the independent states.

The sense of elementary survival in the Soviet Union in those days was palpable. It usually had to do with food. Like Soviet citizens, I carried a bag everywhere I went because I never knew what might suddenly turn up. Hustlers would appear on a street corner, unload cardboard boxes full of produce, and start hawking their goods. It might be Ecuadorian bananas, Cuban grapefruits, or Polish jam. Whatever it was, I bought a lot of it and carted a sagging backpack home.

Procuring food was a metaphor for scratching out a life in those topsy-turvy days of change. A Russian sports entrepreneur captured the mood in the early 1990s when he said: Its a difficult time but an interesting time. I like it very much. Each day Im like a hunter. Where will I get my food? Who will I kill?

The longer I spent in the former Soviet Union, the more I was drawn in. Traveling across the former Soviet republics in the 1990s and 2000s, I met people overcoming hardships to live meaningful lives. A woman sewing new clothes for her daughter out of discarded clothes. People flocking to Eastern religions after prohibitions on worship were eased. Like the food, you would find them in surprising places.

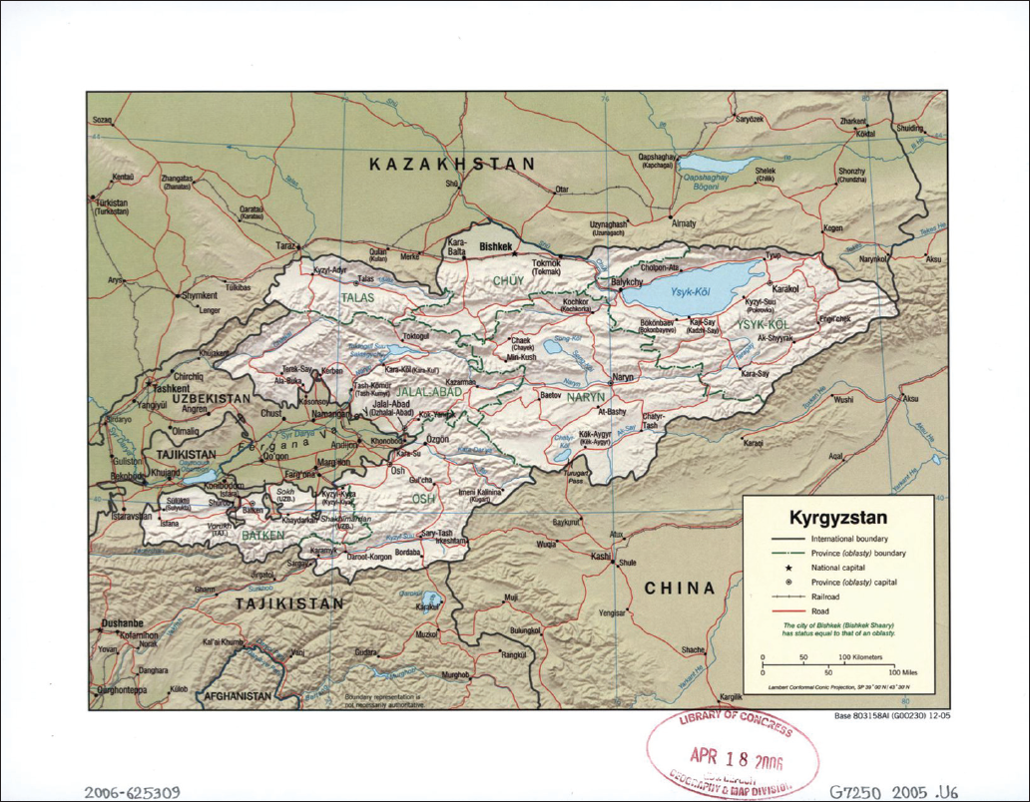

Like Kyrgyzstan. Thats where I met Chingiz Aitmatov in 2007, a writer little known in America but one of the leading literary figures of Researching Aitmatovs life, I learned about his countryman Azamat Altay, a broadcaster for Radio Liberty who fled the Soviet Union after World War II. The more I studied the two men, the more I understood that their life paths were part of a wonderful and tragic tapestry of the twentieth century. Paths connected by a kindred struggle for more freedom for their people. Paths linked by poplar trees.

Altay was born in a mountain village near the border with China. Marooned outside his homeland for more than half a century, he outlasted his archenemy the Soviet Union. Upon his return to Kyrgyzstan in 1995, he went immediately to the site of a cluster of poplar trees that he and his father had planted when he was a young boy, and embraced them. The trees towered over the aging Altay, silent markers to his fifty-year odyssey as a Soviet dissident in Europe and the United States.

During the decades Altay was building a life for himself in the West, Chingiz Aitmatov was cultivating a remarkable literary persona in Soviet Kyrgyzia. Spurred to write by the disappearance of his father during Stalins purges, Aitmatov penned compelling stories featuring spirited characters with a thirst for freedom. His stories were a far cry from the stilted products of Soviet socialist realism demanded by the state.

In one of Aitmatovs first short stories, a teacher plants two poplar trees to inspire a student to spurn an arranged marriage and continue her education. While they will grow and get stronger, you will grow too, the teacher says to the student. You will become a scholar.

The story of Chingiz Aitmatov and Azamat Altaytwo men from a mountainous land in the middle of the Asian continentis a story of a captive peoples aspiration for freedom. One fights from the outside, a dissident hardened by war and steeled by privation; the other struggles from the inside, an intellectual warrior who rises in the Soviet system even as he skewers it in coded prose.

They fought for freedom not with guns but with words and ideas. Their lives are proof that lies live on for only so long; that the truth, as evidenced by the attainment of justice and redemption, is achievable; and that the search for a meaningful life is based on individual freedom.

Defying the Iron Curtain, Aitmatov and Altay met and pursued a shared dreamto preserve their culture and help make the Kyrgyz people more free and independent. This is the untold story of two men from an unfamiliar land whose lives were connected like poplar trees growing side by side, their branches intermingling and overlapping with the passage of time.

NOTE TO READERS

Altay was known by two names: Azamat Altay (Al-tai), which he adopted in the early 1960s in the United States, and his birth name Kudai-bergen Kojomberdiev (pronounced Hoo-dye-bear-gen Ko-zhom-bear-dee-yeff). Chingiz Aitmatovs name is easier to pronounce: Ching-geez Ait-matt-off. A note on transliteration appears following this preface.

The second clarification has to do with their homeland. When it was part of the Soviet Union, it was a Soviet republic, known officially as the Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic, or Kyrgyzia for short. After Kyrgyzia became an independent country in 1991, it changed its official name to the Kyrgyz Republic but is commonly known today as Kyrgyzstan. Using an i or a y has to do with transliteration. For simplicitys sake, I spell the root word Kyrgyz when referring to the country or its people.

And, finally, on pronunciation, via a bit of personal history, since people are usually befuddled when it comes to pronouncing the countrys name. When I landed a job in Kyrgyzstan in 2004, my father, a diplomat who himself had traveled to far corners of the world, congratulated me on the upcoming adventure with my young family in tow: So, you are taking Lynn and the boys to Gurkistan? He was passable on the last syllables but got fouled up on the first. Others mistake it as Kurdistan. In 2013, Secretary of State John Kerry called it Kyrzakhstan, and in 2015 the