Preface and Acknowledgements

This book comes out of several years of happy bonds of intellect, friendship and family. Almost ten years ago, when I accepted a temporary lectureship position at the state university of Zacatecas, I had little knowledge of the Cristero revolt which shaped the state and wider region which I have since come to know and love. Travelling through Zacatecas state and the Jalisco highlands, visiting local museums run by enthusiasts, witnessing the commemoration of religious martyrs (even of some priests killed in the Spanish Civil War) and the emblazoning of hillsides with Hollywood-style letters Viva Cristo Rey!, all brought the topic to life for me on a personal level even when my academic research interests still lay elsewhere. Over time I decided to take the plunge. My background researching war and radicalism in modern Spain perhaps gave me more preparation than most historians daring to embark upon a new topic in a new continent. But I could not have developed the momentum to write a regional study without the love and support of family members and the friendship and networks I have been fortunate enough to enjoy over the past few years.

My thanks go first of all to my wife and daughter, Susana and Nicole, who have long put up with my interest in the Cristero War. They never complained of my erratic visits to remote regions in the Altiplano and lengthy stays in archives in the region and in Mexico City. My thanks especially go to Miguel Acosta, whose interest in the topic and in history generally was the cause of several interesting conversations and visits. He showed me great generosity, hospitality and support. My thanks also go to my good friend, Nathaniel Morris. His insights into indigenous involvement in the Cristero War and wider Mexican history have been invaluable and inspiring. It was always great fun to welcome him to the comforts of Zacatecas on several occasions after he had spent long periods living frugally among the indigenous communities of the Sierra.

My thanks also extend to colleagues. Luis Rubio has been very generous with his time and insights, as has Ben Fallaw. Matthew Butler and Keith Brewster read and approved of my proposal to write a regional study with a military angle and have been very welcoming to a scholar whose main work so far has been on Spain rather than Mexico. Mexican archivists have been universally friendly and helpful, especially those working in the smaller state and municipal archives. It has been a pleasure to meet Fernando Villegas, chronicler of the municipality of Guadalupe in Zacatecas. I hope that our discussions about opening the first-ever state museum dedicated to the Cristero War bear fruit soon. Friends and family in Mexico are almost too numerous to mention, suffice it to say that they are all very dear to me and that they have all helped me in various ways with this project.

Canterbury, April 2019

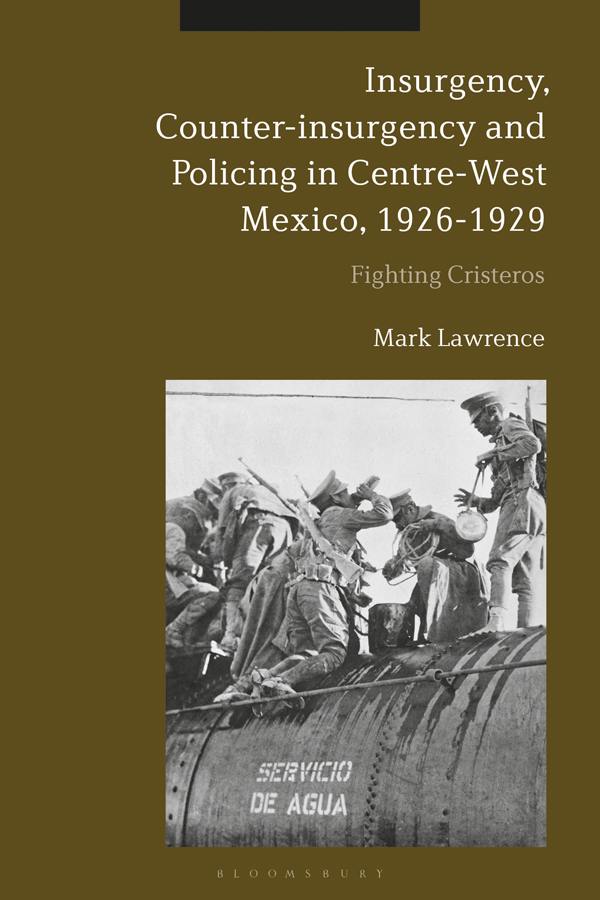

Origins, context, historiography

The Cristero War (19269) was a popular convulsion made in protest against enactment of the Mexican Revolutions anticlerical constitution of 1917. It was ultimately the most violent and divisive episode in Mexico between the 1910 revolution and the ongoing Narco Wars. The war has generated significant historiographical attention in recent years, especially in relation to the states of Michoacn and Jalisco, and is also increasingly the object of attention outside the academy. The breakthrough of regional studies in the 1970s and the loosening grip of Mexican revolutionary hegemony have improved our understanding of the 19269 Cristero revolt against Federal anticlericalism. Far from being a revolt of fanatics in cahoots with landowners, the Cristero rebellion had diverse motives and interests. Yet there are still gaps in our understanding. How, for example, was peaceful opposition to anticlericalism expressed in Mexicos centre-west? What civilmilitary tensions existed in government-held areas, and how did these compare to those of the insurgent zone? In what ways did local power networks ( cacicazgos ) shape decisions to support or defy the government, and how were these informed by social, cultural and economic tensions? This new history, the first regional study of the Cristero War to be centred on the state of Zacatecas, answers these questions, adapting models applied in regional studies elsewhere and offering fresh perspectives in equal measure. Instead of studying the Cristeros in isolation, this book explains how the communities on both sides of the Cristero/Federal divide showed similar responses to the demands of militarization and displacement of population, and how the proximity of cruelty and killing produced similar spirals of violence. Fighting Cristeros shows how the war in Zacatecas and the centre-west hinged less on ideology and more on long-standing local tensions, vertical rather than horizontal lines of allegiance, and on the autonomy of highland ( serrano ) culture hostile to central control.

This book aims to develop leads established by such historians as Lourdes Celina Vzquez Parada and the late Alicia Olivera, who placed regional and oral history firmly on the map of the Mexican historiography, as well as the classic trilogy of the Franco-Mexican historian Jean Meyer. Nonetheless, there are still opportunities for new research in several directions. Matthew Butlers pioneering 2004 study of diverse and non-violent Cristero activism in Michoacn revised the dualist emphasis on overt militancy offered in Jean Meyers classic 1970s study and led to calls by experts, including by Meyer himself, for more studies of non-combatant responses to the Cristero War, including in regions untouched by fighting.

A regional history

Fighting Cristeros studies the Cristero War in Mexicos centre-west, the state of Zacatecas and the adjoining bordering areas of Jalisco, Durango and Aguascalientes, parts of what is sometimes referred to as Mexicos Rosary Belt. Zacatecas, a largely underpopulated state, has not been subject to a new military history study of its Cristero conflict. This is remarkable considering that the Federal war minister, humble-born Joaqun Amaro, and one of the leading Cristeros, Aurelio Acevedo, both came from the state. Jean Meyers classic trilogy included substantial material on the state, thanks to his privileged access to the papers of General Aurelio Acevedo of Valparaso (Zacatecas). But this book does not claim to follow Meyers nationwide study. Rather, it considers Zacatecas and the adjoining centre-west states as an enclosed theatre of war and the Cristero rebellion waged within it as a kind of asymmetrical warfare. It explains how the geography, Catholic traditionalism and serrano culture of Zacatecas and the centre-west predisposed this region to suffering a very embittered insurgency in the Cristero War. It also explains how the recent revolutionary experience of the Mexican army led to both a brutal counter-insurgency and crises in civilmilitary relations. The persistence of the Cristero War in the Zacatecas region was determined not just by the clash between a ruralized militant traditionalism and an urban-based political and military counter-insurgency, important though these were. Rather, terrain, poor communications, economic dislocation, civilmilitary crises and defiant local power networks all combined to give the war its prolonged and asymmetrical features in this region.