Thank you for buying this ebook, published by NYU Press.

Sign up for our e-newsletters to receive information about forthcoming books, special discounts, and more!

Sign Up!

About NYU Press

A publisher of original scholarship since its founding in 1916, New York University Press Produces more than 100 new books each year, with a backlist of 3,000 titles in print. Working across the humanities and social sciences, NYU Press has award-winning lists in sociology, law, cultural and American studies, religion, American history, anthropology, politics, criminology, media and communication, literary studies, and psychology.

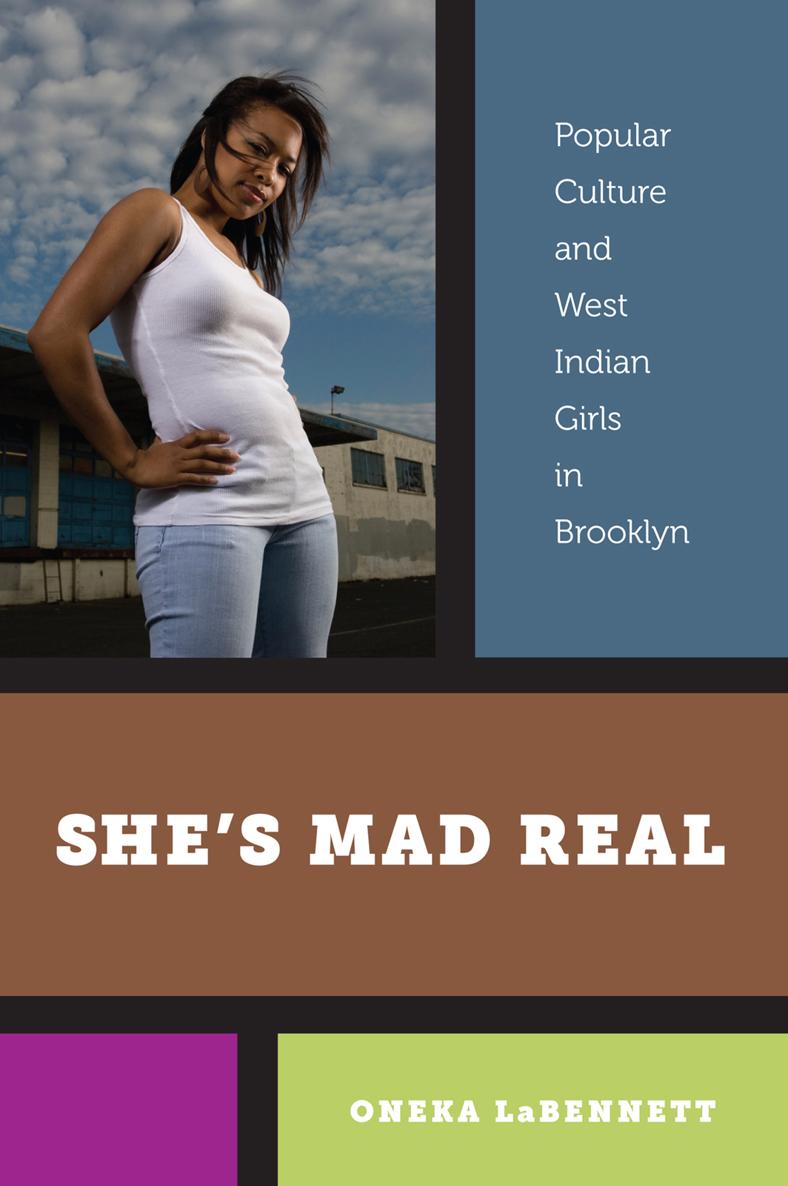

Shes Mad Real

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2011 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

LaBennett, Oneka.

Shes mad real : popular culture and West Indian girls in Brooklyn / Oneka LaBennett.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780814752470 (hardback) ISBN 9780814752487 (pb) ISBN 9780814753125 (e-book)

1. African American girlsNew York (State)Brooklyn. 2. Minority youthNew York (State)Brooklyn. 3. West IndiansNew York (State)BrooklynSocial life and customs. 4. Consumer behaviorNew York (State)Brooklyn.

I. Title.

HQ1439.N6L33 201

305.23520899697290747275dc22 2011005520

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

Because this project developed over the course of a decade, I had to rely on generous support from many people without whom I could not have completed this book.

My greatest thanks goes to the adults and youth in Brooklyn who shared their stories and experiences with me. I owe a debt of gratitude especially to the Museum Team interns and staff at the Brooklyn Childrens Museum, who welcomed me and allowed me to hang out with them. I hope this book enables readers to hear their voices and to appreciate their vitality and resilience in the face of popular representations and policy discourses that are not attuned to the complexity of their subjectivities.

As an undergraduate student, the world of academia mystified me, and I was fortunate to connect with Elizabeth Traube, Ann duCille, Lydia L. English, and Steven Gregory, brilliant professors who initially sparked my interest in anthropology and who continue to serve as intellectual(s) heroes.

My advisers at Harvard University, Mary M. Steedly, James L. Watson, J. Lorand Matory, and Mary C. Waters, animated and guided me.

Early on, I received a faculty research grant from College of the Holy Cross, and I thank my former colleagues from that time, especially Daniel Goldstein, Susan Cunningham, and James Manigault-Bryant.

This project came to fruition after I joined the faculty at Fordham University, and I am grateful for the faculty research grant and the faculty fellowship I received from Fordham. My colleagues in the Department of African and African American Studies each offered immeasurable assistance in the form of friendship, feedback, and professional support; my sincerest appreciation goes to Mark Chapman, Jane Edward, Amir Idris, Claude Mangum, Fawzia Mustafa, Mark Naison, Carina Ray, Irma Watkins-Owens, and Nol Wolfe, and to everyone with whom I have worked under the auspices of the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). I am also indebted to Glenn Hendler in American Studies, Allan Gilbert in Sociology and Anthropology, Arnaldo Cruz-Malav in Latin American and Latino Studies, and my Fordham students who have advocated for my courses.

At crucial junctures I benefited greatly from critical commentary and reassurance generously provided by O. Hugo Benavides, Daniel HoSang, and Raymond Codrington, whom I owe tremendous thanks. I would also like to acknowledge colleagues whose kindness bolstered me and whose work invigorated me: Elizabeth Chin, Deborah A. Thomas, Jacqueline Nassy Brown, and Jennifer Tilton.

I am extremely thankful to Jennifer Hammer, my editor at NYU Press, for her commitment to this project and for her invaluable suggestions, which sharpened the books readability considerably; to Andrew Tiedt, who devoted his expertise to my demographic statistics; to Danielle Jakubowski, who meticulously transcribed interviews; and to anonymous reviewers, whose insightful criticism, coupled with a keen awareness of my projects vision, enlivened and enhanced this work.

My friends and family have sustained me through numerous challenges. Thank you, David Drogin, Nicole Davis, Dominique Kim, Enas Hanna, and Melissa Woods for years of friendship, and thank you, Mom, Ray, and Don, for your love.

Finally, my deepest love and thanks to my husband, Shawn McDaniel, whose devotion, patience, and loving encouragement fortified me. You were a constant source of inspiration, a ready ear, and a willing proofreader whose presence simultaneously soothed and motivated me. Our years together have been my happiest even amid struggle and hard work. You and Mr. B bring joy to my life!

1

Consuming Identities

Toward a Youth CultureCentered Approach to West Indian Transnationalism

China takes the A train to the Fulton Street/Broadway Nassau stop to get to her job as a sales clerk at a clothing store near Ground Zero, one of two after-school jobs China holds. It is just after 4 p.m. on a Friday in August, and, on this particular afternoon, China rides the train with her best friend, Nadine, and two other friends, Neema and Mariah. The subway car is full of businesspeople leaving early from Wall Street jobs, vacationing tourists, and a few local New Yorkers of varying ethnicities. The businesspeople are mostly White and dressed in suits. The tourists, dressed in shorts and tee shirts with cameras swinging from their necks and purses held close, are also White. Both the tourists and the businesspeople appear to be uneasy sharing such close quarters with the Black teenage girls. China and Nadine wear jeans, tight tee shirts, and sneakers, while Neema and Mariah wear cotton shorts with matching tank tops, and inexpensive, trendy sandals. The four girls are acutely aware of how the other commuters regard their presence on the subway car. The girls seem to spontaneously react to and feed the avoidance and the silent disapproval of the White passengers by yelling loudly across the subway car, taking up more seats than they need, and laughing boisterously. China, whose hair is dyed the same shade of gold as that of her idol, the R&B/hip-hop singer Mary J. Blige, is listening to her iPod. She sits on the opposite side of the subway car, facing the other girls. China sings loudly over the divide, entertaining her friends (who are in hysterics at her poor singing) and visibly annoying the other commuters around her.