Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

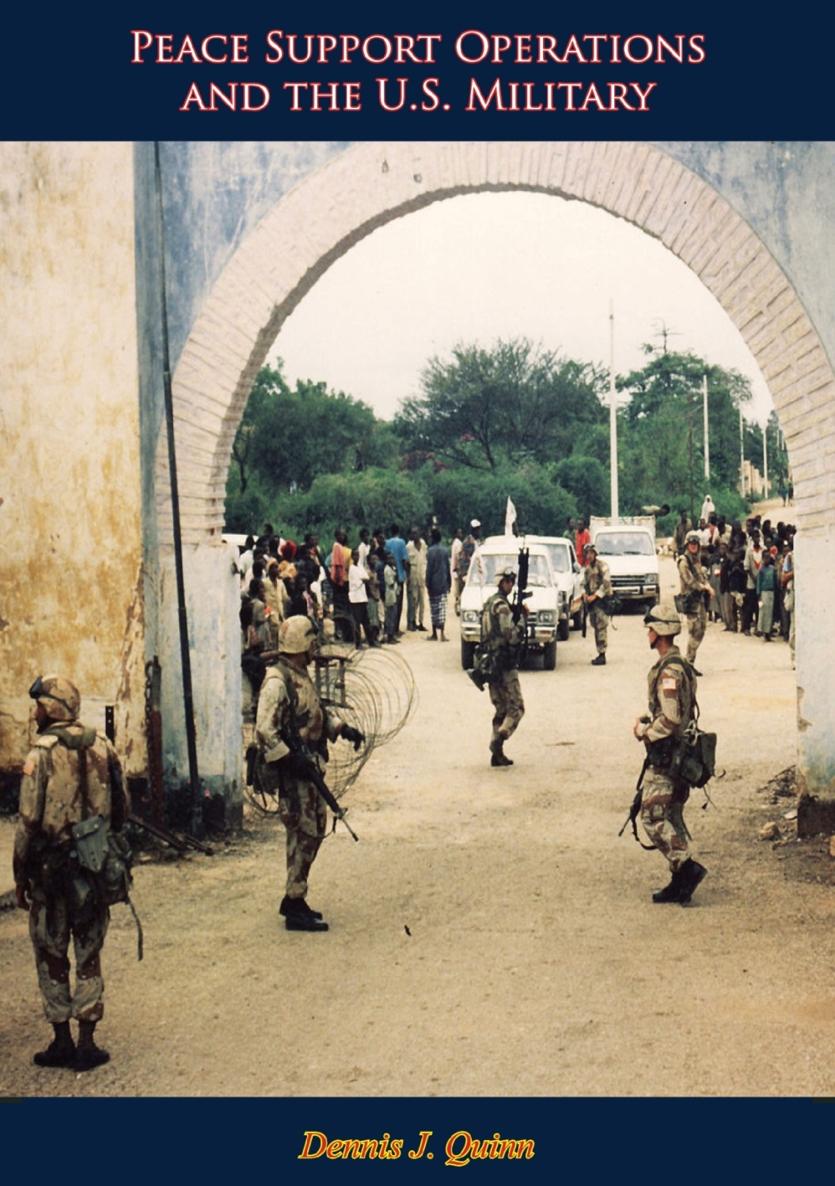

Peace Support Operations and the U.S. Military

Edited by

Dennis J. Quinn

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Foreword

The role of the United Nations as the major international organization chartered to preserve peace and discourage aggression has broadened steadily since the Cold War ended. Regional security concerns are concomitantly replacing global ones as the superpower standoff fades from the world stage. The role of the militaryparticularly the United States militaryis changing both to support UN efforts and to meet a spurt of regional instabilities that could affect U.S. national interests.

The military may be called upon to support the United Nations in five mission areas: preventive diplomacy, peacemaking, peacekeeping, peace enforcing, and peace building. Two questions are paramount: How the military should carry out such missions, and, indeed, whether the military should be involved in some of them. To provide an appropriate forum for addressing the question of how and debating the matter of whether , the Institute for National Strategic Studies hosted the Symposium from which these Proceedings have emerged.

After officials, authorities, and scholars had discussed the five missions, they analyzed UN operations in Bosnia, Somalia, Cambodia, and the Middle East. Using the lessons learned in those operations, they then projected two important considerations: (1) how existing international organizations and coalitions might support future UN missions, and (2) what the implications would be for the U.S. military. These Proceedings collect the very timely papers presented at the Symposium as well as summaries of the cogent analysis and lively debate that followed.

The National Defense University was pleased to support such a comprehensive and intellectually challenging Symposium and gratified with the gravity, good will, and pragmatism of the discussions, as well as the very large attendance at the sessions.

PAUL G. CERJAN

Lieutenant-General, U.S. Army

President, National Defense University

Introduction Dennis J. Quinn

The world is staggering towards its new order. The United States is searching for its role in this new world. The U.S. Armed Forces is husbanding its resources, honing its capabilities, and awaiting its orders. One of the many possible major missions for these forces in this new world order is that of peace support operations.

Beginning with the destruction of the Berlin Wall, half of the old world order began to crumble and soon lie in ruins. With the disappearance of this old counterweight, the remaining half of the old world structure at times seems to be tottering. Many of the Western worlds political, economic, and military policies were driven by the existence and the goals of the Soviet Union and its Communist empire.

The disappearance of the Soviet Empire requires a reordering of Western and Third World interests, goals, and policies. New political and social engineers with new designs and new materials are needed to first shore up the world structure and then redesign it, reorder it, and reinvigorate it with new purposes and methods.

As occurred after past world wars, the United States is leaning towards world government as a means to help achieve its global goals of political and economic democracy. After World War I, the U.S. and many other countries looked to the League of Nations to secure a new world order. It was not to be. After World War II, the U.S. and many other countries looked to the United Nations to secure a new world order. Again it was not to be. Now after the Third World War, i.e. the Cold War, the United States and many other countries are again looking to a world organization, again the UN, to ensure peace and stability in the world.

In 1992 the UN Secretary General, Boutros Boutros-Gali, aware of the new opportunities for the UN, wrote a forceful pamphlet titled, An Agenda for Peace. In this pamphlet he exhorted the countries of the world to take a strong hand, under UN leadership, in fashioning world peace. There was even a call for the use of military might, under the UN flag, to enforce, or even to force, peace in situations where the world community thinks it necessary.

The United States for its part, both in word and deed, seemed to support this agenda. Both Presidents Bush and Clinton and their leading administration spokesmen gave speeches or drafted policy papers indicating strong U.S. support for these new UN peace policies. Even more dramatically, U.S. forces engaged in or led major UN operations in three different regions of the world: in the Gulf, in Somalia, and in ex-Yugoslavia.

A new major mission, peace support operations, was evolving for the U.S. Armed Forces. As should occur with newly evolving missions, a national debate began over the use of U.S. forces in UN peacekeeping and peace enforcement operations. This debate became more focused and intense as a result of events in Somalia on 3 October 1993. It was on that date that U.S. forces, operating under UN orders, suffered 18 soldiers killed in action and more than 70 wounded.

One month later, on 2 and 3 November, the National Defense University held a previously scheduled symposium on UN military coalitions and what implications such UN operations had for the U.S. military. This book you are reading, Peace Support Operations and the U.S. Military contains many of the papers and presentations prepared for or delivered at that symposium. The subject matter in this book is organized into three parts: military perspectives, policy perspectives, and regional perspectives on peace support operations.

Part I provides a wide spectrum of military perspectives. The first article, the symposiums keynote presentation, by LTG McCaffrey provides a big-picture snapshot of the present condition of UN peace operations, U.S. force structure and capabilities, and the opportunities and challenges of using U.S. forces in support of UN peace missions. The remaining articles in Part I, as well as those in Parts II and III, address particular aspects of General McCaffreys keynote presentation.

At the high end, or the strategic end, of this spectrum of military perspectives, General Sewall evaluates the command and control assets needed by the UN, the Department of Defense, and the major U.S. commands, if peace support operations are to be conducted effectively. He makes specific, clear, and low-cost recommendations on ways to satisfy some of these command and control needs. Other strategic views are presented in Dr. Kahans article in which he synthesizes the presentations of British Argentinean, and American generals, all of whom had experience commanding forces in peace support operations. Admiral Miller, Commander of US, discusses the challenges involved in mobilizing, equipping, and training troops for global peace support operations. He does not support the creation or earmarking of specific units for peace support operations. Rather he supports the concept of selecting units from a wide array of available forces and placing these units in ad hoc force packages specifically designed to achieve the particular mission goals of individual peace support operations.