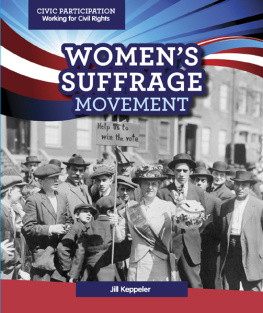

NEW ZEALAND women were given the right to vote in Parliamentary elections in 1893. Women had voted in Wyoming since 1869 and in Utah since 1870, women property-holders in the Isle of Man since 1880; Colorado gave women the vote, with New Zealand, in 1893, and South Australia followed the next year. New Zealand was thus the first national state in the world to allow women to vote, yet New Zealand historians have taken little interest in the event. There appear to be three trends of thought on the subject. Some historians have claimed that there was no agitation for the vote, that it was passed by chance or by the idealism of the early Liberal party. who, in contrast to Reeves, revealed the extent to which women themselves had campaigned for the suffrage, but who attempted little analysis of the mainspring of the womens activities.

This book is designed to show that the concession of the vote in New Zealand was the outcome of a feminist movement comparable to movements elsewhere in the world. To support this it is demonstrated that the grant of the suffrage was not an isolated event, but one contemporaneous with many other parallel changes in the position of women in New Zealand, and that the issue itself was forced into prominence by an organization, the Womens Christian Temperance Union, whose motives in campaigning for the vote were basically feminist. This involves a consideration of the relation between feminism and temperance in nineteenth-century New Zealand, in order to suggest how it was possible for women temperance advocates to be also genuine feminists.

Little has been published on the subject. The Australian suffrage movement appears to have followed a markedly similar course, but has not been investigated in any detail. Elements in the British, the European , and, especially, the American movements illuminated aspects of the New Zealand situation. The most useful primary sources, apart from the newspapers and parliamentary debates, proved to be letters in the Hall collection, correspondence received by the woman suffragist leader Mrs Kate Sheppard, minutes of the Womens Christian Temperance Union, and temperance journals.

For permission to see papers in their possession I should like to thank the Wellington headquarters of the Womens Christian Temperance Union, the late Mrs A. Long, Miss H. Lovell-Smith, Mrs B. Holt, Mr H. Roth, and the late Mr J. T. Paul. I am most grateful to the many relatives of women suffragists who willingly gave interviews; to Mrs H. Lord, formerly of the Auckland Public Library, and to Miss J. Walls of the Turnbull Library. Above all I should like to express my gratitude to Professor R. M. Chapman and Professor Keith Sinclair for their helpful guidance throughout my research.

Melbourne,

1970

Preface to the 1987 Edition

It is pleasing that the current interest in womens history in New Zealand has warranted a second printing of WomensSuffrageinNewZealand. While womens history has become amazingly complex and diversified in the fifteen years since this study was first published (a phenomenon which I deal with in my Afterword), nevertheless a narrative of a feminist campaign continues to provide a useful basis for analysing historically womens social status and cultural expectations. WomensSuffrageinNewZealand explored a group of colonial women who held high hopes for the efficacy of a civil liberties campaign to transform womens unequal access to social power. Working in isolation from both womens history and feminist activism, my early response was one of surprise at the prominence of this previously hidden campaign, and at the courage and competence of the feminists themselves. Subsequent studies have raised problematic issues about these womens motives and goals. Nevertheless the book represented a discovery of an important group previously hidden from history, and their story still deserves to be read and appreciated. My thanks to Elizabeth Caffin of Auckland University Press for her encouragement of a second printing, and to Raewyn Dalziel for her advice.

Notes

. e.g., J. B. Condliffe and W. T. G. Airey, AShortHistoryofNewZealand. 7th ed., Christchurch, 1953.

. e.g., A. Siegfried, DemocracyinNewZealand. London, 1914. F. Parsons, TheStoryofNewZealand. Philadelphia, 1904.

. W. Sidney Smith, OutlinesoftheWomensFranchiseMovementinNewZealand. Christchurch, 1905.

A N American woman historian, analysing the role women have been accorded in the worlds historiography, has described their function as parallel to that of comic interludes in Shakespeares tragedies. Male historians have described the reigns of kings, the battles of soldiers, and the administrations of presidents. Women have been relegated to a passing mention in narrative-breaking chapters on social life, dress styles, family structures and similar diversions. But the position of women during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries underwent a gradual but none-the-less startling change which, while it was classified as proper history in those male historians categories, has not been subjected to extensive analysis until recent years. The stimulus behind this change in womens social position, its essential nature, and its significance for contemporary civilization are still matters for conjecture. This enormous revolution in womens status, whether early or late, eventually influenced almost every community on earth. In order to see in perspective one aspect of this revolution, the womens suffrage movement in New Zealand, it is therefore illuminating to consider briefly how this small section fitted into the large jigsaw pattern of events.

The sentiment or goal that women should have social, economic, and political equality with man became known as feminism. The fundamental wish of feminists was that women should have autonomy in the determination of their lives; that they should be allowed to define for themselves the areas which they would or would not enter, according to their individual talents and potentialities. Their continual cry was that women should be regarded as people, rather than as the female relatives of people. In Victorian society, as over past centuries of civilization, womens lives were governed by the doctrine that there existed a so-called womans sphere. They were to bear and rear children and attend to household affairs. The only extension of this role permitted outside the home was into the area of church and charitable activities. Womens education, such as it was, aimed at fitting them for this role. Economically completely dependent on the male, their subordination was enscribed in man-made laws regarding their property, their rights over their children, and their duties within marriage.

This was the time-hallowed situation that the so-called feminist movement sought to change. The great initial stimulus appears to have been the ideas of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and of the French Revolution, with their emphasis on the egalitarian and democratic ethic. The subsequent demand for personal freedom this entailed led a few of both sexes to question whether these new liberties should be limited to the male sex only and to question for the first time the justice of the traditional subjection of women. The cry of the French revolutionaries for liberty, equality and fraternity echoed strongly through the first published treatise in the struggle to remove womens disabilities, Mary Wollstonecrafts