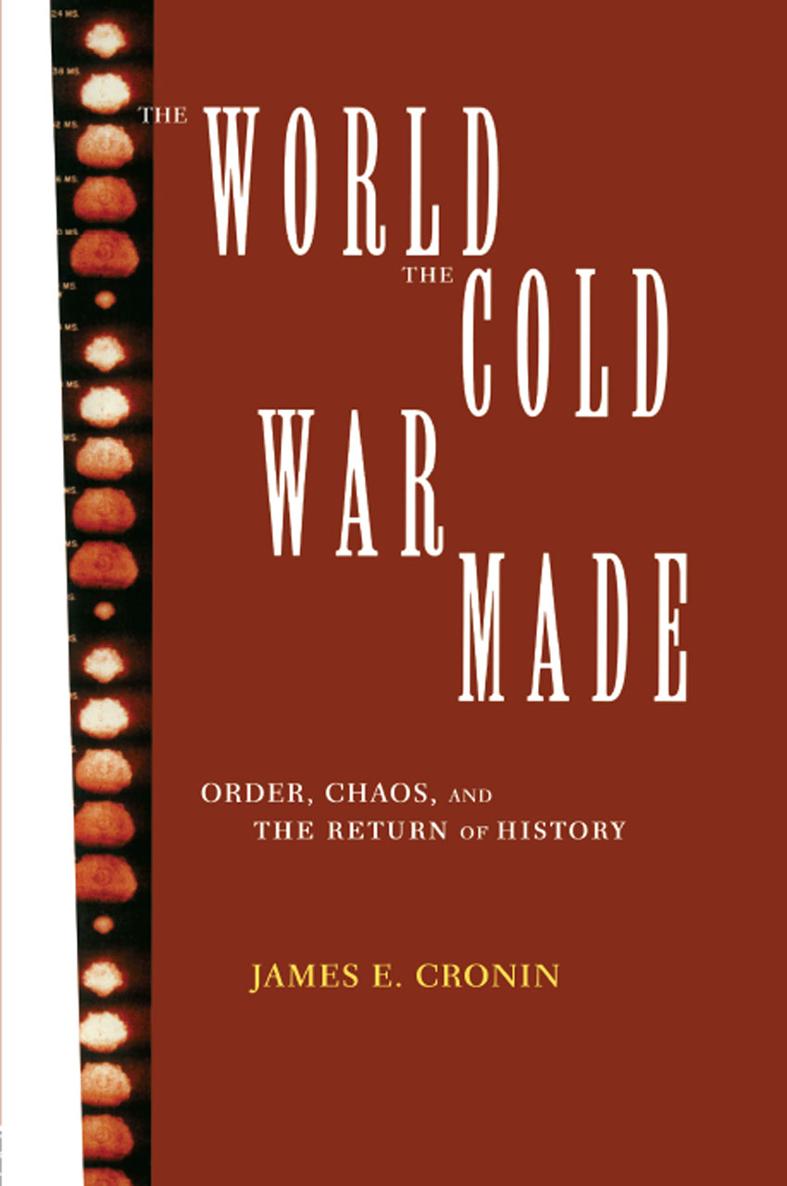

Published in 1996 by

Routledge

270 Madison Ave,

New York NY 10016

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2009

Copyright 1996 by Routledge

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cronin, James E.

The world the Cold War made: order, chaos and the return of history / by James E. Cronin.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-415-90820-5. ISBN 0-415-90821-3 (pbk.)

1. Cold War. 2. World politics1945 I. Title.

D843.C6881996

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent.

The Cold War is over. What shall we make of it? The question must be posed with particular urgency at present, for it is essential to have at least a provisional understanding of the world that has recently ended if we are to make any sense at all of the more confusing and possibly more treacherous world bequeathed to us by the passing of the Cold War. Not only is it necessary to begin to summarize and interpret the era of the Cold War; it is now also possible to do so in a new way. So long as the Cold War lasted and engaged our passions and political identities, scholarship suffered. The problem was not a matter of bias so much as the way in which the ongoing character of the phenomenon prevented scholars from stepping back and viewing it broadly. So long as the arms race persisted and the United States and the USSR confronted one another in strategic locations around the world, it was inevitable that the Cold War would be understood primarily in terms of foreign policy, defense, and war-making, rather than as a world order composed of states whose internal structures were linked to their place in the geopolitical rivalry of the superpowers and in which were embedded rival social systems guided and described by contrasting ideologies. The ending of the Cold War, then, offers historians the possibility of studying the phenomenon anew, of constructing a narrative with a beginning and an end and many exciting moments in the middle, and, in the process, the opportunity to grasp its dynamics and consequences.

This book took shape gradually and indirectly. It began with a course that I taught during the late 1980s at Boston College with my colleague Peter Weiler. The course was called A Historians Guide to World Chaos, the title lifted from G. D. H. Coles A Guide Through World Chaos, written during the Depression as a tract for the times. Initially, the focus was on various crises and zones of conflict: the arms race and the Second Cold War, conflicts in the Middle East, South Africa, and Latin America. But as the Cold War world began to disintegrate in 1989, the focus of our course inevitably broadened to include the Cold War itself as the structure upon which postwar history had been founded and whose rise and fall now called out for renewed attention and analysis. That expanded task led to the present book. Ideally, it would have been researched and written jointly by Peter Weiler and me, and I am sure the outcome would have been more comprehensive and judicious and marred by fewer mistakes. But different timetables and prior commitments prevented that potential collaboration. The result is a book whose virtues, such as they are, are a shared responsibility but whose flaws are all mine.

No book stands entirely on its own, but few books are as dependent on others as this. Its scope required a wide reading in the secondary literature, supplemented in key places by further digging, and its interpretive framework came from an implicit dialogue with other scholars seeking in their own ways to understand the evolution of the postwar world. I began this book thinking that relatively little work of value had been done on contemporary history. I end it with great respect for what is in fact a growing body of highly sophisticated work on recent history and for its authors. This changed perspective stems in part from greater familiarity with the accumulated scholarship in diverse fields that had previously escaped my attention, but a good part comes from the tremendous outpouring of scholarship that seems to have been stimulated by the dramatic transformations of recent years. I cannot hope in this book to match the breadth displayed by Eric Hobsbawm in his Age of Extremes (1994), the reach of Paul Kennedys Preparing for the Twenty-First Century (1993), or the narrative power of Martin Walkers The Cold War (1994), but the publication of these and numerous other titles has provided models to emulate, arguments with which to agree or disagree, and the inspiration to move ahead. This book has different purposes and makes a rather different argument than any of these others, but it could not have been written without them and would have looked very different if it had preceded, rather than followed, their impressive achievements.

It is impossible to distinguish clearly between the intellectual debts acknowledged formally in notes and the practical debts accumulated in writing a book of this sort. Part of the reason is that quite a few books and articles utilized here came to my attention in draft form, courtesy of authors willing to share their emerging thoughts and analyses. I am grateful in particular to Harold Perkin, Daniel Chirot, Moshe Lewin, John Stephens, and Robert Brenner for offering me early or easier access to work in progress, to Peter Bush for providing me with an advance copy of his translation of Juan Goytisolos important article, and more generally to Peter Hall and George Ross, whose seminar at the Center for European Studies at Harvard has served for many years as a sounding board for much of the best work in political economy. I profited as well from discussions of the project with Eric Hobsbawm, Jrgen Kocka, Richard Price, Lou Ferleger, Jim Shoch, and Gary Cross, who arranged for me to present a summary of my ideas to a colloquium at Pennsylvania State University. I was fortunate also to be invited by the International Institute of Social History to lead a seminar in Moscow during the summer of 1995 and thus given the opportunity to view up close the debris left behind by the collapse of Soviet socialism. Particular thanks for this are due to Marcel van der Linden and to Irina Novicenko, head of the Moscow program.