ESSAY

The South in Red and Purple

Southernized Republicans, Diverse Democrats

by Ferrel Guillory

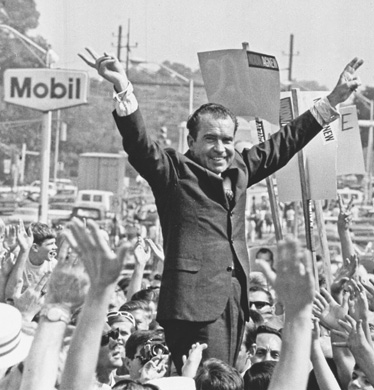

A Republican Southern Strategy emerged out of the Barry Goldwater campaign of 1964, Richard Nixons narrow victory in 1968, and then the 1969 book, The Emerging Republican Majority, by Kevin P. Phillips, who served in the Nixon campaign. However, President Obamas 2008 wins in Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida revealed enough political change to give a Democratic candidate a chance to pick up electoral votes in the South. Nixon on the 68 campaign trail, courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Twenty-four years ago, both the Democratic and Republican parties held their national conventions in cities of the American South. Democrats gathered in Atlanta to nominate Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts for president, and Republicans assembled in New Orleans to nominate George H. W. Bush of Texas. To mark the arrival of Democrats in his cityand mindful that Republicans would subsequently meet way down yonderBill Kovach, then editor of the Atlanta Journal and Constitution, commissioned a series of essays on the southern condition by seventeen eminent historians, novelists, and journalists. Their essays were collected after the 1988 election in The Prevailing South: Life & Politics in a Changing Culture.

It has been a long time since the South has enjoyed the feeling of being really wanted and needed in the national business of electing a president, historian C. Vann Woodward wrote in the opening of his essay for the book. But now, rather suddenly, and for the first time in history, both major political parties have held their presidential nominating conventions in the Deep South.

The 1988 conventions had the aura of a historic milestone, and their sites seemed ready-made for the every-four-year exercise in political liturgy. Atlanta had decisively emerged as primus inter pares as the Southeasts major metropolis, with its international-hub airport, its tall towers standing sentinel along Peachtree, and its magnetic pull to in-migrants both black and white. New Orleans had long served as a conventioncity, with its Vieux Carr at a dramatic bend in the Mississippi, its splendid restaurants, and its landmark domed stadium.

Now, in preparing for the 2012 presidential election, both major political parties have again chosen cities in the American South for their national conventions. Republicans convene first in Tampa, and, a week later, Democrats meet in Charlotte. The 2012 conventions have a different feelless about history, more about the politics of the moment. Until now, neither Tampa nor Charlotte would have readily come to mind as natural destinations for big political conventions. No doubt they were chosen in part because Florida and North Carolina will be in play as competitive states in the November general election. Whatever the politics of their selection, Tampa and Charlotte stand as exhibits of what the modern South has become; the regions center of gravity has shifted toward an array of recently developed, sprawling, muscular metropolitan areas that now increasingly define its economy, culture, and politics.

While the South is often depicted as resistant to change, Woodward wrote in his 1988 essay that change, in fact, has long been a central theme of Southern history, prodigious change of such degree and frequency as to become one of the regions several distinctive traits. The independent decisions of Republicans and Democrats to choose sites in the American South for their national conventions offer a fresh opportunity to examine the latest manifestations of what change has wrought in the life and politics of the region.

FIVE BIG TRENDS

In considering the condition of the South and how the region fits into the national political fabric of 2012, lets identify and examine five big trends:

1. Politically, the South is not an assembly of states, acting in unison, in the grip of one party. The region is not one South, undivided.

2. While its rural heritage and culture still exert a strong pull on the regions own self-image and on the nations imagination, burgeoning metropolitan areas now decisively dominate the economy and increasingly propel the politics of the South.

3. Whither Texas? It has remained stubbornly Republican even as it has become a multi-hued state of whites, blacks, and Latinos, without an ethnic or racial majority.

4. The recessions of 20002010 delivered a stunning blow to the South, knocking the region off its fast track of progress. Still, among many southern voters, cultural and social concerns trump economic issues at the ballot box.

5. The center of gravity of both the Democratic and Republican parties has shifted. The national GOP has grown southernized, while Democrats have found it difficult to sustain their New South agendas in an age of austerity.

For the purposes of this analysis, the South consists of the eleven former Confederate states, plus Kentucky and West Virginia. These thirteen states account for 173 of the 270 electoral votes needed to elect a president, up from 166 in 2008 as a result of population growth. In the 2008 election, Republican John McCain carried ten of these states; Democrat Barack Obama carried three: Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida, for an aggregate of 55 electoral votes.

MUCH RED, SOME PURPLE

It remains tempting to view southern politics as a monoculture, as Vanity Fair magazine described it recently. Indeed, for half of the twentieth century, the South was a one-party region, with white Democrats in control in every state and practically unified in the preservation of rigid racial segregation. While deftly capturing nuances of each states politics, V. O. Key Jr. could write in his 1949 master-work, Southern Politics in State and Nation, that maintenance of white supremacy formed the backbone of Southern political unity.

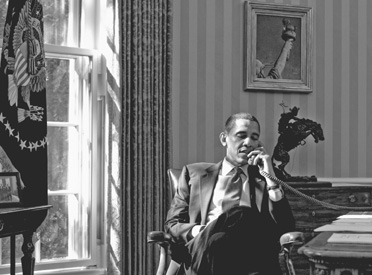

On his way to the Oval Office, Barack Obama won 365 total electoral votes, well more than the 270 needed for victory. Thus, he would have captured the White House even if he had lost the three southern states that he carried. Still, it is significant that the Obama campaign targeted three once-upon-a-time Confederate states and carried them. Barack Obama, Oval Office, 2010, photographed by Pete Souza, courtesy of the White House.

The national Democratic Partys embrace of the civil rights agenda, culminating in the 1965 Voting Rights Act, destabilized the so-called Solid South. A Republican Southern Strategy emerged out of the Barry Goldwater campaign of 1964, Richard Nixons narrow victory in 1968, when he divided the Souths electoral votes with former Alabama governor George Wallace, and then the 1969 book, The Emerging Republican Majority, by Kevin P. Phillips, who served in the Nixon campaign. With law-and-order rhetoric and signals that the Nixon administration would ease enforcement of school desegregation, the Southern Strategy was designed to win over conservative and segregationist white Democrats and Wallace voters. Watergate intruded, and Democrat Jimmy Carter of Georgia won the presidency in 1976. But then, in his victorious 1980 campaign, Ronald Reagan solidified what Goldwater and Nixon had started. In addition to adherents gained through the Southern Strategy, Republicans received a party-building boost from an enlarged suburban middle class as regional economic expansion made the Old South part of the rising Sun Belt. Since 1980, the American South has served as an essential base of the national GOP. For roughly a quarter of a century, the GOP has had what was described as an electoral lock on the South.