THE SOVIET UNION IN EAST ASIA

The Royal Institute of International Affairs is an unofficial body which promotes the scientific study of international questions and does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors.

The Institute and its Research Committee are grateful for the comments and suggestions made by Hugh Seton-Watson and Paul McDonald, who were asked to review the manuscript of this book.

The Soviet Union in East Asia

Predicaments of Power

edited by

Gerald Segal

First published 1983 by Westview Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Royal Institute of International Affairs 1983

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 83-50813

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-29616-2 (hbk)

Contents

by Gerald Segal

by Malcolm Mackintosh

by Christina Holmes

by J. David Armstrong

by Wolf Mendl

by Gerald Segal

by Lawrence Freedman

by Kazuyuki Kinbara

by Gerald Segal

Tables

We are indebted to a number of people and organizations for help in the preparation of this book. The study group meetings in the first half of 1982 were funded by the Social Science Research Council. The Royal Institute of International Affairs provided excellent facilities for these meetings and some members of staff provided especially crucial assistance. In particular, Dr Adeed Dawisha not only ran his usual tight ship so that the study group participants could wander freely on deck, but also took an active and helpful part in most of the discussions on the papers. Miss Ann De'Ath of the RIIA continued to steer the ship through the tricky stages of cajoling contributors into revising drafts, meeting deadlines and calming the often anxious editor. More anonymous debts are of course owed to the participants in the study group who often made trenchant comments, and thanks are also due to the Institute's two readers, Professor Hugh Seton-Waton and Dr Paul McDonald, who spotted errors in the final draft that we all missed first time around.

G.S.

December 1982

David Armstrong, Lecturer, School of International Studies, University of Birmingham

Lawrence Freedman, Professor of War Studies, King's College, University of London

Christina Holmes, research associate, Royal Institute of International Affairs, London

Kazuyuki Kinbara, staff economist, Keidanren (Federation of Economic Organizations)

Malcolm Mackintosh, consultant on Soviet affairs, International Institute for Strategic Studies, London

Wolf Mendl, Reader, Department of War Studies, King's College, University of London

Gerald Segal, Lecturer, Department of Politics, University of Leicester

Gerald Segal

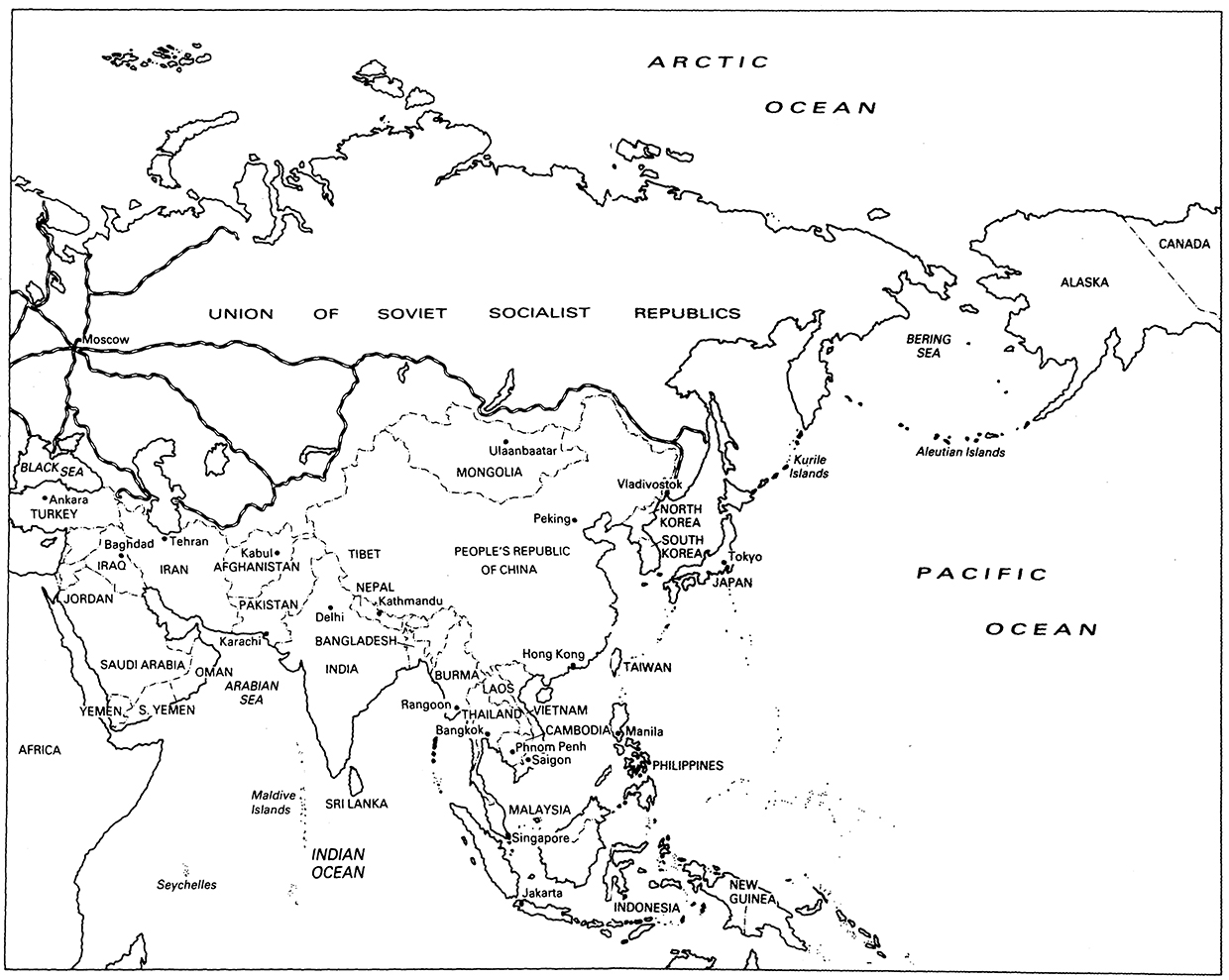

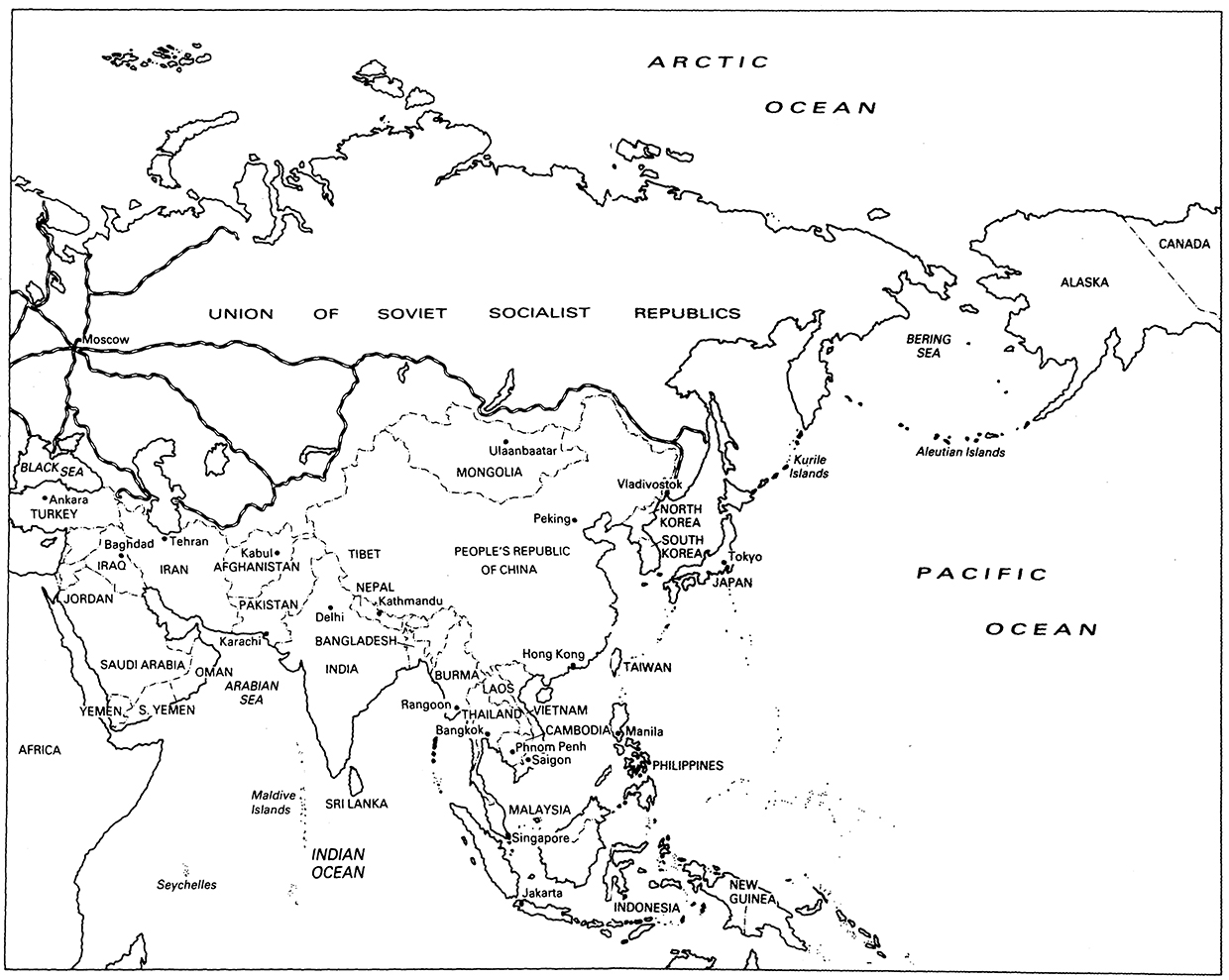

The Soviet Union is not an east Asian power, but it is a power in east Asia. Other than its European frontiers, no other territory is as vital to Soviet interests as the vast border with east Asia. Thus the essential enduring dilemma of Soviet east Asian policy is set: how to develop a constructive foreign policy in an area where the Soviet Union is overwhelmingly viewed in a hostile light.

This Soviet predicament of power has no simple solution. Three major and very different powers confront the Soviet Union in the area, each of which demands different responses from Moscow. Chinese power, the predominant problem in east Asia, must be met with vigour, but not so much that Beijing is driven to extreme hostility. US power is regional, but more importantly it is also part of a global competition with the Soviet Union. Japanese power is overwhelmingly economic and offers opportunities for beneficial ties to the Soviet Union, but also threatens to buy influence elsewhere in the region at Moscow's expense. Thus the Soviet Union must live not only with different powers in east Asia, but also with different dimensions of military, political and economic relations.

While these predicaments of power are in many senses obvious, it is striking how few analyses have been produced of Soviet policy in east Asia. To be sure, there are excellent more detailed studies of specific aspects of Soviet policy in the region, especially concerning SinoSoviet relations. There is also at least one attempt to study Soviet policy in Asia as a whole, but it concentrates less on the Soviet perspective.

It is not by accident as the Soviet Union is fond of saying that these books are similar. Whether called dilemmas, problems or predicaments, what is clear is that the Soviet Union has no easy foreign policy options. Like any great power, the Soviet Union finds it difficult confidently to pursue a coherent and consistent strategy in a complex and confusing world.

This latest study of Soviet attempts to live with its predicaments is organized into essentially two main sections, one looking at bilateral Soviet relations, and the other assessing key issues in Soviet policy. These main sections are preceded by a chapter in which Malcolm Mackintosh sets the scene for Soviet east Asian policy. His main theme, and one that runs through much of the book, is the failure of the Soviet Union to become well integrated as an Asian power. The essential features of the Soviet Union remain European, even if the major part of Soviet territory is non-European. Mackintosh suggests that this fundamental problem for Soviet policy arises not merely because the Soviet Union has chosen to remain European, but also because the local states of east Asia do not see the Soviet Union as one of their own. Thus Moscow has found it easier to approach east Asia primarily in balance of power terms, trying to make sense of the contradictory pressures from the local powers as well as its fellow superpower, the United States. Mackintosh also makes plain the centrality of China for Soviet strategy in east Asia, and the continuing inability of the Kremlin to evolve a satisfactory policy for controlling hostility in SinoSoviet affairs.

China, as the primary problem for Soviet strategy, is the first of the bilateral relations studied in the first core section of the book. Christina Holmes suggests there are no simple solutions to Soviet dilemmas. SinoSoviet relations are seen as more naturally hostile than amicable, but the level of that hostility need not remain as high as in recent years. The sources of conflict are deep, rooted in geography, ideology and politics. But as strong as these roots might be, they do not necessarily mean that the Soviet Union has no option but to allow China to sway into alliance with the West. Indeed Christina Holmes makes it plain that there are some possibilities of at least a modicum of dtente. She is also careful not to be mesmerized by short-term fluctuations in policy, and asserts that Moscow can find no escape from the dilemmas of SinoSoviet relations.