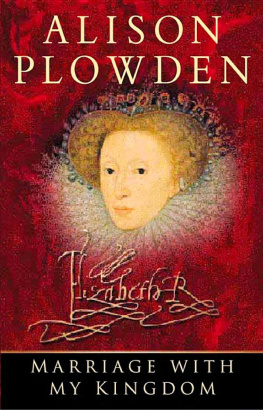

Strange Bedfellows

POLITICS AND CULTURE IN MODERN AMERICA

Series Editors: Margot Canaday, Glenda Gilmore, Michael Kazin, Stephen Pitti, Thomas J. Sugrue

Volumes in the series narrate and analyze political and social change in the broadest dimensions from 1865 to the present, including ideas about the ways people have sought and wielded power in the public sphere and the language and institutions of politics at all levelslocal, national, and transnational. The series is motivated by a desire to reverse the fragmentation of modern U.S. history and to encourage synthetic perspectives on social movements and the state, on gender, race, and labor, and on intellectual history and popular culture.

Copyright 2018 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lefkovitz, Alison, author.

Title: Strange bedfellows: marriage in the age of womens liberation / Alison Lefkovitz.

Other titles: Politics and culture in modern America.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, [2018] | Series: Politics and culture in modern America | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017046028 | ISBN 9780812250152 (hardcover: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: MarriageUnited StatesHistory20th century. | MarriageUnited StatesHistory20th centuryPublic opinion. | Domestic relationsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Marriage lawUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Womens rightsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Sex roleUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Public opinionUnited States.

Classification: LCC HQ535 .L36 2018 | DDC 306.810973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017046028

In the inaugural issue of Ms. Magazine, the feminist activist Judy Syfers proclaimed that she would like a wife. A few pages away in this same issue, Johnnie Tillmon, the president of the National Welfare Rights Organization, critiqued not only the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program but also marriage. She proclaimed that all women were domestic slaves, and even marriage provided wan protection or pay for this labor.

Outside of the pages of Ms., other Americans debated marriage. Divorced mens rights activist Charles Metz, for example, opened his own book-long manifesto on marriage reform in 1968 with a triumphant recognition that noise is swelling from hundreds of thousands of divorced male victims. God help us to swell this noise, still a whimper, into a roar of indignation that will be felt in every court and legislative body in this Union of States and their Federal Government. Phyllis Schlafly, similarly, decried the Equal Rights Amendment for its potential danger to the institution of marriage broadly and to wives in particular. The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) identified sham unions as one of the main threats to the nations borders. Gay men and lesbians, meanwhile, dressed in drag to try to win marriage licenses from oblivious bureaucrats and then went to local newspapers to call attention to their exclusion from marriage.

In other words, a broad array of Americans identified marriage as a problem in the 1960s and 1970s, and the subsequent changes to marriage law at the local and federal levels constituted a legal revolution. But legislators and courts instituted these changes unevenly to ameliorate the problems they identified as the most dangerous, rather than give activists exactly what they had asked for. These new policies replaced the more blatant gender and racial inequalities that courts and legislatures had stripped out of the law during the civil rights revolution. Like law and order campaigns and the War on Drugs, the legal revolution in marriage at once instituted formal legal equality and also created new forms of political inequality that historianslike most Americanshave yet to fully understand.

The difficulty began with the legal foundations of marriage. Half a century after the long struggle for votes for women had secured an amendment to the nations founding document, wives and husbands were still sharply distinguished not only in popular culture and private life but also in law. State laws nationwide obliged wives to perform nearly all of the homemaking tasks that Syfers catalogued in Ms.; wives unpaid labor in the home still belonged to their husbands in practice and in law.

Yet husbands had their own gendered obligations to fulfill, characterized above all by the duty to support their wives and children. Though a wife had to bring her case to court, the government enforced a husbands financial duties as spouses entered and left a marriage.

Beginning in the 1960s, a feminist revival worked to dismantle this system. Different feminists advocated for different ideas ranging from the total destruction of the institution to more cosmetic changes. Liberal feminists had the greatest success at reforming the law, but even among them, two different concepts of equality rivaled one another. One was what I call expansionistit sought to keep the protections that wives enjoyed by extending them to husbands as well. Wives could take care of their husbands just as husbands had traditionally taken care of wives. The other concept of equality was individualistit sought to make wives roles equal to husbands financially and in law by compensating women for their household labor at the point of divorce, retirement, or widowhood. Neither spouse would have to take care of the other over time. Both visions of equality had some significant though mitigated effects on marriage law, which changed but without fully accounting for the vast gender difference that persisted within the home and in terms of jobs, income, and wealth.

Feminists redefining of the marriage relationship led husbands to question their roles as well. Many husbands increasingly resented their support obligations as wives began rethinking their roles as homemakers. Most husbands were not well organized, but many nonetheless backed away from breadwinning obligations en masse in the 1970s. Other husbands, like Charles Metz, founded divorced mens groups that sued or lobbied to free men of these obligations. And though these groups were not the most effectively organized of activist bodies, their claims seemed to resonate with state legislatures and courts who limited mens support obligations.

Feminists and divorced husband groups questioning of the marriage relationship also coincided with welfare, immigration, and gay marriage activists rising demands that lawmakers treat their families equitably. While their specific goals and who they counted as a family varied, all three of these emerging social movements asked the government to provide the same legal recognition and financial support that traditional families received. This diverse array of advocates on the left also made use of the changing legal ground, new resources, and new strategies forged by the civil rights and feminist movements to make demands such as extending gender-neutral obligations to all families or decoupling benefits from family relationships entirely. The resources and strategies had their limits, however. While the feminist movement won a moderated victory in the form of greater legal equality between husbands and wives, these activists gained even less.