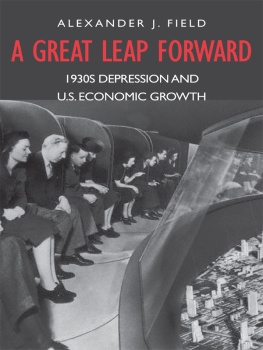

Technological Innovation and the Great Depression

First published 1995 by Westview Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1995 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-28960-7 (hbk)

Contents

PART ONE

THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS

PART TWO

SECTORAL ANALYSIS

Guide

I have always been intrigued by the enigma of the Great Depression, perhaps because my parents often told tales of their experience of the 1930s in drought-stricken western Canada. Only in the late 1980s, though, did I begin to develop the theoretical approach of this book. I was helped at an early stage by a paper presentation at Northwestern University, and the lengthy conversations with Joel Mokyr and Lou Cain which that entailed.

Much of the first draft of this book was completed while I was on sabbatical at the University of New South Wales in 19912. John Perkins organized a one-day workshop on the Depression at which I was one of the speakers. I received a great deal of helpful advice that day and during my entire stay from many people, including Alex Blair, Craig Freedman, Peter Kriesler, Ian Inkster, John Lodewijks, and John Perkins. I also benefitted from being able to present papers at the University of Newcastle, Australian National University, the University of Western Australia, and Curtin University. I gained insights of great value at each of those places, and thank John Fisher, Mac Boot, Graeme Snooks, and Malcolm Tull for having made those visits possible.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the entire school of economics at the University of New South Wales for the tremendous hospitality which they bestowed upon me. Special thanks must go to David Meredith, Ross Millboume, and Bob Conlon, who occupied the key administrative posts while I was there. The School of Economics provided, at the time, a wonderful melange of respected scholars representing varied viewpoints. I hope that those in charge can overcome the temptation to turn it into just another mainstream economics department, for surely the world already has enough of these. I was blessed not only with the friendship and intellectual insights of all those above, and others such as Lance Fisher, Frank Barry, and Barrie Dyster, but also the warm smile, masterful typing, and encouragement of Charleen Borlase. And even this, let me be clear, is only a partial list.

Since my return to North America, I have had the opportunity to present some of this material at the meetings of the Economic History Association and the Nineteenth Conference on the Use of Quantitative Methods in Canadian Economic History. Both of these occasions aided me considerably as I revised the manuscript. I would like to thank Morris Altman in particular for some sage advice.

I have been aided over the years by two grants from the Central Research Fund of the University of Alberta related to this book. As always, I have benefitted greatly from the advice and encouragement of Mike Percy, Ken Norrie, and Melville McMillan. Charlene Hill has finished typing that which Charleen Borlase had begun. One can only hope that shortsighted government budget cuts will not destroy the positive environment which made this book possible.

Finally, let me thank Alison Auch and the staff at Westview Press. It has been a pleasure dealing with them.

Rick Szostak

Part One

Theoretical Considerations

1

The Great Depression Revisited

Most economists would agree that we have as yet no widely accepted explanation of the Great Depression. Various theories have been put forward, and some are felt to be capable of explaining some, though far from all, of the calamitous events of the 1930s (as we will see in ). The situation is ripe for a new approach. The purpose of this work is to proffer a technological explanation of much of the Depression experience. While Schumpeter (1939) and others, especially at the time of the Depression, have suggested that technology played a substantial role in causing the Depression, the approach pursued here is quite novel. I will detail in the next five chapters a theoretical explanation of how an abundance of labor-saving production technology coupled with a virtual absence of new product innovation could affect consumption, investment, and the functioning of the labor market in such a way that a large and sustained contraction in employment would result. I will also describe how such a technological situation could have arisen historically. In the succeeding several chapters, I will provide evidence at the industry level that these technological forces were at work, and that they were powerful enough to generate most of the observed unemployment in the 1930s.

The fundamental premise of this work is that the key to understanding the Great Depression is to be found through analysis at the industry level rather than through the highly aggregated research that has dominated the field in the past. This does not mean, of course, that we can turn our back on the concepts of macroeconomics. We must, indeed, couch our analysis carefully in a general equilibrium framework. It is too easy to describe why some sectors of the economy went into decline in or near 1929. This may provide limited insight into why the Depression began, but can tell us little about why recovery was so slow. We must understand why the resources released by some sectors did not indeed, could not flow smoothly into other sectors. Why didnt the labor market clear? Once we remove some simple misconceptions about the functioning of the labor market, and the determinants of consumption demand, we will find that the answer to this question is also to be found at the industry level.

We can already see that there is not just one Depression question. Why was the initial turndown so severe? Why was recovery so slow? We can add others. Why was the recovery to 1936 so feeble and so overwhelmed by the downturn of 1937? How was the Depression transmitted around the world at a time when links between nations were much weaker than today? On the other hand, why did some countries, such as Britain, fare so much better than others in the 1930s? Most previous works have tended to focus on only one of these questions. There is, naturally, no logical necessity that the same factors provide the answer to all. It would, though, be an awful coincidence for a number of horrible events to occur in a short time period for quite different reasons. I will, in what follows, outline an approach which can deal with all of these questions.

This does not mean that I am pursuing some simple monocausal explanation of the entire Depression experience (though I must inevitably focus on my own theoretical approach to the exclusion of others in much of what follows). As Scitovsky (1986) so aptly put it, Nothing is ever so simple that a single explanation will adequately explain it. Certainly the Great Depression is not so simple. As noted above, the existing literature does adequately explain some of what happened, but is unconvincing in its attempt to explain the entire Depression. My purpose is to fill much of that gap.