Contents

The Fur Trade Years

The Rise of the Hudsons Bay Company

The Struggle to Control the Fur Trade

Free Traders

St. Paul Connections

Prelude to Confederation

Becoming the Fifth Province

Louis Riel and the Red River Resistance

Treaties

Mtis Land

Winnipeg Business Community: The Early Years, 18701880s

The Rise of the Wheat Economy

A Changing HBC

Early Entrepreneurs

Establishing a Board of Trade

End of the Land Boom

Competition for the CPR

After the Boom: Winnipeg at the Turn of the Century

The Lumber Business

Wholesalers and Retailers

A Second Era of Growth

Developing the Agricultural Industry

Building the Aqueduct

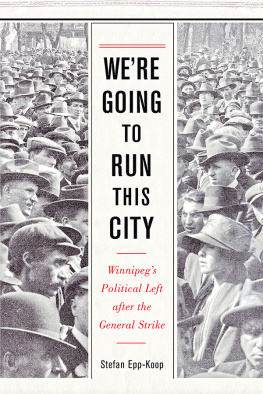

Winnipeg General Strike, MayJune 1919

Growth of the Industrial Economy: Winnipeg in the 1920s and 1930s

Board of Trade

Freight Rates

The Garment Industry

The Changing Wheat Market

The New Fur Trade

Great-West Life

Winnipeg Electric

North Star Oil

The Fur Trade Years

The land occupied by the modern City of Winnipeg was once

covered by the massive Laurentide glacial ice sheet, which receded

and advanced several times over a period lasting thousands of years. The ice sheet finally melted during a period of climate warming between 9,500 and 5,000 years ago, completely disappearing

7,500 years ago. The meltwater created Lake Agassiz. Where Winnipeg now stands was the bottom of a lake that at its greatest extent covered most of modern Manitoba and extended into Ontario and

North Dakota.

When the lake began to recede from the Winnipeg area and southeastern Manitoba emerged from the water, birds, animals, and people moved into the area. Archaeological work at the Forks Historic Site has revealed clear evidence of human beings camped in the area 3,000 years ago.

The 80,490 artifacts found in archaeological digs at the Forks tell us quite a bit about the people camping there. The large number of fish bones indicate that people were catching, eating, and perhaps preserving fish from the rivers. The various projectile points present at the site show that people from at least three different cultural groups were likely camping in the area. The flint that the arrowheads and tools found at the site were made of came from North Dakota, eastern, western, and southwestern Manitoba as well as the Lake Superior area. The artifacts confirm that Indigenous people from different areas came together at the Forks in order to trade with one another.

Some of the artifacts were made from Knife River flint, a highly valued stone from an area on the modern border between North and South Dakota. It was used to make strong and durable projectile points, knives, axes and hide scrapers. Flint was widely used because of its hardness and the fact that it could be shaped by skilled flint knappers to produce high quality tools and weapons. Knife River flint blades and arrowheads were desirable trade goods for people who did not live near a source of good quality flint.

In pre-contact Indigenous cultures, as in all cultures, trade was a way for different groups of people to obtain tools and materials they did not otherwise have access to. To many ancient North American peoples, trade also had an important role in diplomacy and was part of the formalities used to seal treaties and agreements. That trading sessions between different Indigenous groups and, later, Indigenous and Europeans were accompanied by ceremonies, music and dancing testified to the importance of the activity.

Writer Niigaan Sinclair has described the movements of the Indigenous people who met at the Forks in more recent times.

From the north many Cree travelled seasonally on Lake Winnipeg and south along the Red River to meet and trade with relatives. From the west the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota travelled east along the Assiniboine River and, while sometimes conflicting with the Anishinaabeg and Cree, hunted bison along a migratory path and ended up here tooFrom the south the Anishinaabeg travelled up the Red River and joined with other communities to help birth the Selkirk Treaty of 1817, officially welcoming Europeans and eventually the Selkirk Settlers.

Recently, elders have resurrected the ancient Cree names for the forks of the rivers. The area south of the junction of the Assiniboine and the Red is called Niizhoziibean and the area north of the Forks has the name Musogotewi.

The Rise of the Hudsons Bay Company

For the Indigenous people of what is now Canada, trade was an important part of intercultural relations, and when Europeans began to visit the east coast to fish, the local population naturally began to trade furs with them. In return, Indigenous people secured iron tools, weapons, and cooking vessels. When Jacques Cartier visited the Atlantic coast in 1534, the local Mikmaq people invited the French to trade. He wrote that they showed a marvellously great pleasure in possessing and obtaining iron wares and other commodities. He described the ceremonial acts that accompanied the trading, including dancing and going through many ceremonies. No doubt Cartier also felt a marvellously great pleasure in acquiring the valuable furs the local people brought to trade.

The fur trade had many negative aspects for the Indigenous

populations that participated in it. Those trading furs with the Europeans slowly abandoned their usual ways of living, their foods and economy. Diseases like smallpox, much more lethal to the Indigenous population than to Europeans, brought great loss of life. Trade goods like rum disrupted communities.