Philip H. Gordon

The Transatlantic Allies and the Changing Middle East

Adelphi Paper

First published September 1998 by Oxford University Press for

The International Institute for Strategic

Studies 23 Tavistock Street, London WC2E 7NQ

This reprint published by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX 14 4RN

For the International Institute for Strategic Studies

Arundel House, 13-15 Arundel Street, Temple Place, London, WC2R 3DX

www.iiss.org

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

By Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

The International Institute for Strategic Studies 1998

Director John Chipman

Assistant Editor Matthew Foley

Design and Production Mark Taylor

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Within the uk, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms and in other countries should be sent to the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

ISBN 978-0-199-22377-0

contents

AIPACAmerica-Israel Public Affairs CommitteeAramcoArabian-America Oil CompanyCFRCouncil on Foreign Relations (US)CFSPCommon Foreign and Security PolicyCIACentral Intelligence Agency (US)ECEuropean CommunityEUEuropean UnionG-8Group of Eight industrial nationsIGCIntergovernmental ConferenceILSAIran and Libya Sanctions ActIMFInternational Monetary FundMENAMiddle East-North Africa economiccooperation summitNACNorth Atlantic CouncilNATONorth Atlantic Treaty OrganisationNTANew Transatlantic AgendaOICOrganisation of the Islamic ConferenceOPECOrganisation of Petroleum Exporting CountriesPAPalestinian AuthorityPLOPalestine Liberation OrganisationUAEUnited Arab EmiratesUNSCOMUN Special Commission on IraqWMDweapons of mass destructionWTOWorld Trade Organisation

Since the mid-1990s, US and European attitudes, strategies and policies towards the Middle East have diverged to a degree that frustrates the search for peace and damages transatlantic relations. Since the Oslo peace process began to break down in 1995, Europeans have grown frustrated with the near-monopoly on regional diplomatic action enjoyed by the US in the Arab-Israeli dispute, and have criticised perceived US partiality towards Israel. The appointment of a European Union (EU) coordinator for the Middle East peace process in October 1996, prominent visits to the region by European leaders and open European disagreement with the Israeli governments policies under Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu have demonstrated Europes renewed desire to play a political role in the region. These developments have also led to tension and disagreement with the US over the future of the peace process, and over the measures required to move it forward.

Transatlantic tensions have been greater still in the Persian Gulf. The EU has opposed the US policy of Dual Containment, meant to deter and contain both Iraq and Iran. Europeans have generally been more willing to believe that Iran is changing for the better, and have maintained dialogue and trade with Tehran. They have also been more reluctant than the US to exert political and military pressure on Saddam Husseins regime in Iraq, less willing to use or threaten military force in response to violations of UN resolutions, and opposed in principle to US attempts to force its strategic outlook for the region on a reluctant Atlantic Alliance. When the US imposed a total economic boycott of Iranian goods in May 1995, and Congress in August 1996 passed legislation designed to punish foreign companies investing in Iranian and Libyan oil development, transatlantic relations over the Gulf deteriorated to possibly their lowest point in more than two decades.

Tension between the US and Europe in the Middle East is not, of course, a new phenomenon. US and European interests and strategies have clashed there since the 1950s, when the US began to displace the UK and France as the main outside power in the region. Differing views of Israels security needs, the Soviet role in the Middle East and relations with oil-producing Muslim states formed the backdrop to sharp transatlantic disagreements over the Suez crisis of 1956, the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973, Israels 1982 invasion of Lebanon and the US bombing of Libya in April 1986. Current differences among the Atlantic allies on how to deal with the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Persian Gulf could therefore be seen as simply another episode in a series of NATO out-of-area disputes. If Americans and Europeans disagree today on how to deal with Iran and Iraq, on whether to pressure Israel or on whether to recognise an independent Palestinian state, no one should be surprised.

If not new, however, transatlantic differences over the Middle East are detrimental to common Western interests possibly even dangerous for at least three reasons. First, divisions among the allies reduce the likely effectiveness of each sides policies.

transatlantic differences harm common interests

Washingtons use of sanctions to deny Iran resources, for example, will have only a limited effect as long as Europe tries simultaneously to influence Tehran with trade, openness and a critical dialogue. Economic sanctions at best uncertain tools of statecraft are more likely to succeed if implemented by a broad international coalition than if imposed by a single country, even one as strong as the US. On Iraq, the reluctance of certain European states, notably UN Security Council Permanent Members France and Russia, to support the use of force or other punitive measures makes it impossible for the US to create a united international front against the regime. Saddams conviction that he could split the international coalition ranged against him probably led him to precipitate a crisis in late 1997-early 1998 by refusing to cooperate with weapons inspectors of the UN Special Commission (UNSCOM).

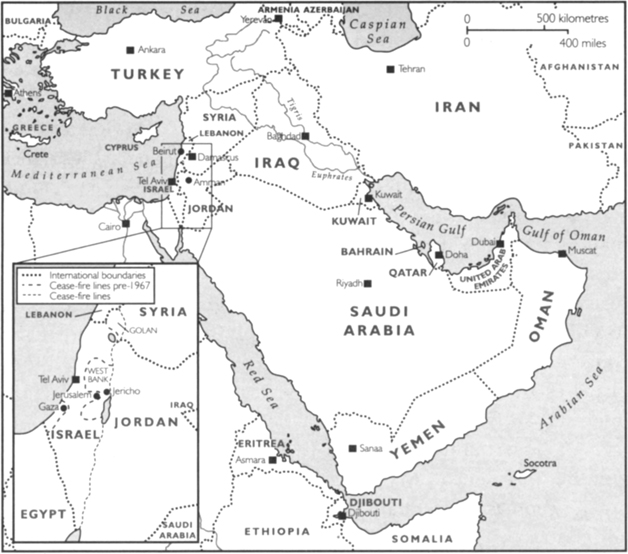

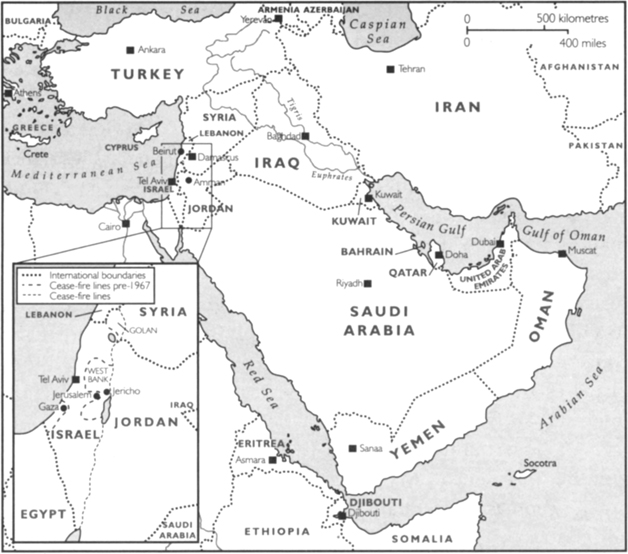

Map IIsrael and the Persian Gulf

Many analysts argue that a harder line from one side of the Atlantic than the other can be useful in resolving crises. Some, for example, believed that French and Russian offers of compromise, together with the US-led threat to use military force, helped to defuse the arms-inspection crisis in February 1998. In fact, however, transatlantic differences usually hinder, rather than promote, the successful use of deterrence and diplomacy. A so-called good-cop/ bad-cop approach when one set of allies takes a hard line, while another seeks engagement may at times be unavoidable given the politics and preferences on each side of the Atlantic. This will, however, always be a second-best alternative to a united US-European front offering a combination of encouragement and restraint.