Preface

Several years ago, after completing a biography of Confederate General John Bell Hood, I began work on a history of the Atlanta Campaign of 1864a then much-neglected military operation that had been very important in the American Civil War. After several months work on the project, I found myself completely bogged down in what was rapidly becoming a three-hundred-page introduction to chapter one of a history of the Atlanta Campaign.

When two other starts produced similar results, I realized that it was going to be impossible to complete the study I envisioned without going into so much background material that the introductory section would constitute a separate book. Such a study would inevitably embrace far more than a simple narrative of the 1864 struggle for Atlanta. It would have to include a detailed examination of the Federal and Confederate armies in the winter of 186364 and of their preparations for the campaign of the following spring and summer. Such a discussion would cover in detail their organizations, their leaders, their personnel, and the overall political and strategic situation in which they found themselves in the spring and summer of 1864.

More work along these lines led to similar problems. It was simply impossible to discuss intelligently the situation in the winter of 186364 without going back to the events that took place in the fall of 1863. Coverage of those events, in turn, necessitated a discussion of what had happened in the preceding summer. Eventually, by following this process, I reached the spring of 1862 and was, I thought, ready to begin to write my history of the Atlanta Campaign. Again, however, it soon became obvious that I needed to go back even earlier. Many of the factorsboth bad and goodthat hampered or helped the two armies struggling in North Georgia in 1864 had their origins in the months before the spring of 1862 when those armies clashed in their first great battle at Shiloh. Many of the factors went back to the first days of the war, and some of them could be traced far back into the antebellum years.

This realization led to the development of a new plan that would both curtail and expand the study. I decided to limit the coverage to the Confederate side but to widen the scope of the work so as to embrace the political, economic, strategic, tactical, organizational, administrative, naval, and logistical facets of the Confederacys war on the western front from the time of secession in 1861 to the end of the war in 1865. Although the focus of the study would be on the Confederates main western military forcethe Army of Tennesseethe sweep of the work would be broad enough to cover in some detail the area from the Appalachian Mountains on the east to the Ozarks on the west and from the Ohio and Missouri rivers on the north to the Gulf of Mexico on the south. The work would bear the title Steps Marked in Blood: The Confederacys War in the West.

It did not matter that the research and writing would constantly be interrupted by other projects (as, indeed, they have been) or that a work on so vast a subject would probably never be completed. Historical research, as my friend Arnold Shankman once remarked, is supposed to be fun. To those of us who have been converted to its study, the western front of the American Civil War was, by far, the most important part of that struggle. Knowledge of its history is of primary importance in our efforts to understand the course of the conflict. The study of its history is time-consuming, frustrating, expensive, and exhaustingbut it is also fun.

One writer on the Rebels western army has said that his idea of heaven is to be able to sit around and talk with the generals who were in the Army of Tennessee and to find out from them what actually had happened at Shiloh, Perryville, Cassville, Spring Hill, and several other points on that ill-starred armys odyssey across the western Confederacy. Such a hope, of course, is predicated upon the shaky assumption that at least some of the generals who served with the Army of Tennessee are in heaven. Since Larry Daniel, the historian who made the statement, is also a theologian, I prefer not to debate the point with him.

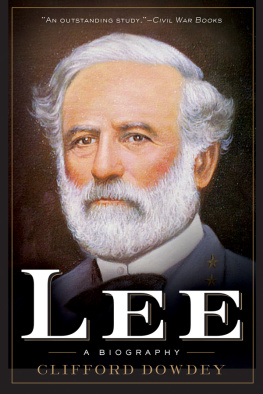

ANYONE who deals in more than a cursory way with the military aspect of the Southern side of the Civil War must, sooner or later, come to grips with Robert E. Lee, his role in the war, and his dominant place in Confederate historiography. During the war, Lee became the hope of the Confederacy, and in the years since the conflict closed he, far more than any other man, came to symbolize what white Southerners liked to believe the Confederacy had been.

In the decades after the war, interest in Confederate military history tended to focus on Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia and their campaigns and battles. The Southern forces that had fought outside the Old Dominion were, for the most part, neglected. Northern as well as Southern writers have usually devoted most of their time and energy to studying the war in Virginia. The towering presence of Lee and the veneration in which he has been held by both Northerners and Southerners in large part account for the skewing of Rebel military history toward the fighting in the East. Even John Fiske, a self-confessed Connecticut Yankee and one of the few early writers to appreciate the importance of the war in the West, admitted in 1900 that he reverently removed his hat when he passed the statue of Lee in New Orleansa gesture that reminds one of Douglas Southall Freemans practice of saluting whenever he drove past the great equestrian statue of Lee that stands on Monument Avenue in Richmond.

In addition to wrestling with the Lee problem, those of us who study the war in the West must also decide what we think about the provocative and controversial ideas put forth over the last two decades by Thomas Lawrence Connelly. Since many of Connellys more polemical and disputed ideas concern Lee, his role in Confederate military history, and his standing in both Southern and national historical literature, these two problems are not unrelated.

As explained in Chapter 9, this book had its beginnings in an effort to focus my ideas about several of the points raised by Connelly in his various assaults on Lee and his reputation. In one sense, then, this book is, in part, an effort to straighten out my own thinking on the subject and to clear the decks of the debris and clutter left by Connellys foray against Lee. In so doing, I hope to remove some of the impediments to the writing of Steps Marked in Blood.

A third major problem with which anyone studying the western Confederates must deal is the necessity of explaining their almost unbroken string of defeats. John Fiske pointed out in the late nineteenth century in a series of lectures and later in