ON THE GEOPRAGMATICS OF ANTHROPOLOGICAL IDENTIFICATIONLoose Can(n)ons

Series Editor: Bruce Kapferer, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, University of Bergen, and Honorary Professor, University College London

Loose Can(n)ons is a series dedicated to the challenging of established (fashionable or fast conventionalizing) perspectives in the social sciences and their cultural milieux. It is a space of contestation, even outrageous contestation, aimed at exposing academic and intellectual cant that is not unique to anthropology but can be found in any discipline. The radical fire of the series can potentially go in any direction and position, even against some of those cherished by its contributors.

Volume 4

On the Geopragmatics of Anthropological Identification

Allen Chun

Volume 3

Heading for the Scene of the Crash

The Cultural Analysis of America

Lee Drummond

Volume 2

PC Worlds

Political Correctness and Rising Elites at the End of Hegemony

Jonathan Friedman

Volume 1

Starry Nights

Critical Structural Realism in Anthropology

Stephen P. Reyna

First published in 2019 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2019 Allen Chun

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages

for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book

may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information

storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented,

without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A C.I.P. cataloging record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Control Number:

2019003726

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78920-203-8 hardback

ISBN 978-1-78920-204-5 ebook

Preface

T he can(n)onical nature of this book series has prompted me to offer an unorthodox perspective on a field of study that I have had ambivalent attitudes about from the inside and have gradually moved away from in disciplinary practice. The two anonymous reviews were instructive: one seemed to be by a cultural studies reader who was positive and focused mostly on various themes that connected the chapters. The second reviewer seemed to be an anthropologist. Although he was critical of specific arguments in the book, he found little to say about the broader themes that meant to crosscut disciplinary debates yet still recommended publication. As reflected in reader reviews, audience reception matters. Despite my anthropological background, I have gravitated long ago toward cultural studies, less to identify anew than to proclaim disciplinary neutrality. At the same time, I do not assume that anthropology is a unified field, given its inherent diversity of voices, although we continue to teach it that way.

I did my PhD at the University of Chicago. In contrast to other departments that I knew, Chicago at that time identified closely with its school of thought. This was not to imply that everyone there equally subscribed to this label, but there was a consensus that it was the standard bearer for a kind of cultural or symbolic anthropology. This school of thought was a major object of scrutiny in Sherry Ortners (1984) Theory in Anthropology since the Sixties. Moreover, Chicago was fiercely theoretical, which made it intolerant of many other schools. As such, it took seriously the broader conceptual foundation on which its approach to anthropology was based. The core course was a classics approach that emphasized eclectic interdisciplinary influences on it. Not surprisingly, Marx, Durkheim, and Weber (plus Lvi-Strauss) mirrored the same ancestors that sociology traced its intellectual roots to. This core course was referred to as systems, a rationalist branding par excellence. In this kind of mind-set, it was heretical to argue that its theory was shaped more by its anthropological relevance or values than by the content of its thought per se. However, this is precisely what I argue. If we trace the traveling of theory over different disciplines, I argue that the relevance of concepts has been routinely disciplined by its discipline in ways that its practitioners do not readily admit. Why is it that some theoriesfor example, classical paradigms, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, and so ontravel more than others? Even when we argue that they have produced revisionist schools of thought, we tend to think that they are revisions by definition or in conception instead of in the way in which different practitioners have appropriated them. Before Foucault systematically developed his notion of discourse, his critique of the emergence of the human sciences flattened theories into broad epistemes that crosscut fields of knowledge. This is contrary to the way in which disciplinary institutions shaped the advent of modern social science. In this latter narrative, our knowledge should be conditioned by institutional practices, with schools of thought being a lesser dependent. Nonetheless, successive eras of grand theory have mobilized intellectual movements in following decades. On the contrary, I would argue that, despite our intellectual openness, disciplinary boundaries have hardened over time, reinforced even more by regimes of assessment, not to mention neoliberal rationalizing. If anything, discursive thought should have mutated accordingly, despite our denial of identification to any disciplinary correctness.

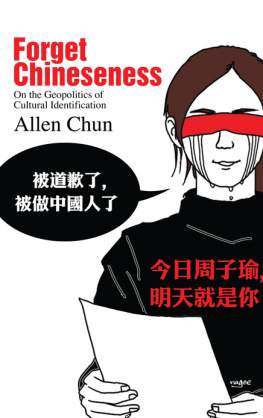

This is a long-winded preamble to explaining the title of the book, On the Geopragmatics of Anthropological Identification. If one is unwilling to believe that anthropologists subscribe to a mind-set that is largely demarcated by the evolution of disciplinary boundaries and practices, despite minor internal differences, then one will react with hostility to anything that follows. This identification is influenced by all manner of things, at the low end from what we call petty politics subsequently to how we carve theoretical spaces, which is ultimately at the high end my object of scrutiny. My definition of identification follows my recent book on Chineseness, subtitled On the Geopolitics of Cultural Identification (Chun 2017), which was an application of an argument about ethnicity, culture, and identity in an essay in Anthropological Theory (Chun 2009). This has been revised extensively as to geopragmatics is less about politics than subjective process. Pragmatics here is a linguistic term for subjective construction of meaning. Geopragmatics is literally about the discursive spaces of our speaking position and their underlying practices. To a large extent, my object of gazing involves axiomatics, in the sense that all conception assumes an unquestioned belief in the underlying axioms that drive the discipline, but one should underscore more importantly that inculcation of such axiomatic beliefs has also been the product of our institutionalization as academic discipline, defined by normative standards and regulated in professional practice.

Allen Chun

Allen Chun

Contents

Contents Preface

Preface