Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

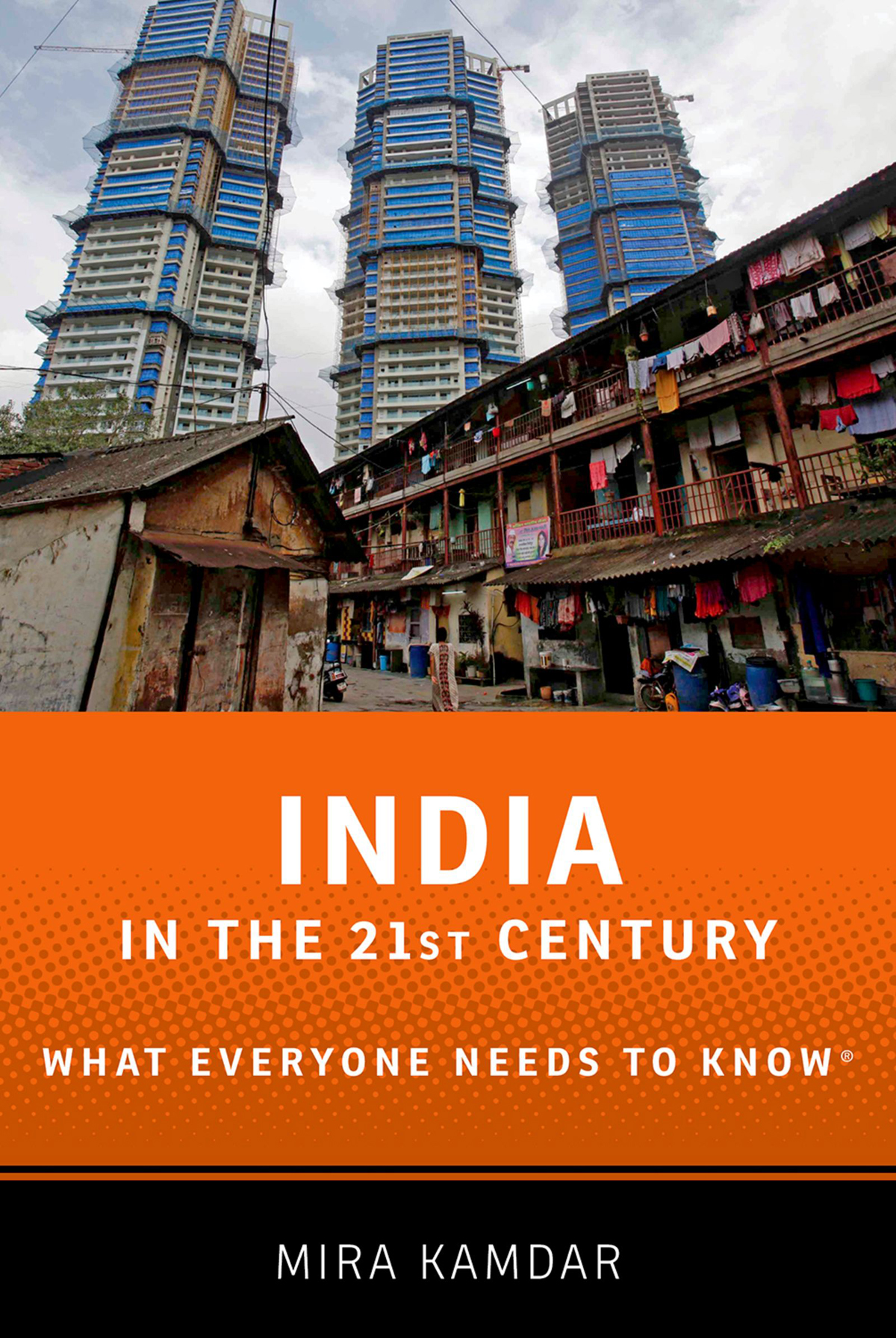

INDIA IN THE 21ST CENTURY

WHAT EVERYONE NEEDS TO KNOW

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

What Everyone Needs to Know is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Mira Kamdar 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Kamdar, Mira, author.

Title: India in the 21st century / Mira Kamdar.

Description: Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press, 2018. |

Series: What everyone needs to know

Identifiers: LCCN 2017046723 | ISBN 9780199973590 (pbk. : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9780199973606 (hardback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780199973620 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: IndiaHistory21st century.

Classification: LCC DS480.853 .K3635 2018 | DDC 954.05/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017046723

CONTENTS

Part I

How India Got to the Twenty-First Century

Part II

Will the Twenty-First Century Be Indias Century?

I first traveled to India from America in 1960 on the Jalagopal, a cargo ship owned by the Scindia Steamship and Navigation Company. Founded in 1919, Scindia was the first Indian-owned and -operated large-scale shipping company, and bore the name of the proud clan that led the Maratha Confederacy, which fought the British in a series of wars beginning in 1775.

I was three years old when we set out from Seattle to Bombay. Of all we experienced on that journey, what I remember most distinctly is the wooden lip that kept the china from skittering off the edge of the dining table as a storm-tossed Pacific Ocean rolled the great freighter from side to side, and the kindness of the crew, who doted on me and my sister. My Danish- American mother had married an engineering student from India, and we were off on a great journey from the West Coast of the United States to visit my fathers family. Passage in the very comfortable officers quarters on a freighter was cheaper than flyinga luxury my parents could not then afford. In those days, my parents communicated with my fathers family by letter or telegram. The rare phone calls went through international operators, who announced: Hello, India. This is the United States calling.

Over the years, I have lived off and on in India. I continue to visit the country frequently, tied by family and friendship and an enduring fascination with one of the most confounding and diverse countries in the world. I speak, read, and write (slowly) Hindi, and I understand a little Gujarati, one of Indias regional languages. I have published books on India, and I have written articles on India for major publications in India, in Europe, and in the United States. As an Overseas Citizen of India, I may soon be able to vote in Indias elections.

Still, distilling India as it moves into this uncertain twenty-first century into one compact book is no easy task. This brief book can only scratch the surface of one of the most ancient cultures and complex countries in the world. Even so, it seeks to give the reader a better understanding of how India got to where it is today, and of how it may evolve going forward. Structured as a series of questions about what I feel are the most essential things to know about India, this book offers what I can best describe as freeze-frame images of a country traveling at multiple speeds on multiple tracks, hurtling forward but sometimes also simultaneously backward, sideways, or cyclically. A tale that originated in ancient India may help explain how I hope this book will work. Versions of the tale are retold in various religious traditions important in India, including Hinduism, Jainism, Sufism, and Buddhism. The tale entered the Western canon in the form of a poem by the nineteenth-century American poet John Godfrey Saxe called The Blind Men and the Elephant. In Saxes poem, as in the traditional tale, several blind men touch a different part of an elephant, and each comes to a different conclusion about what the beast is. The man who touches the tail believes the elephant is a rope. The man who touches an ear concludes the elephant is a fan. The man who touches a leg is sure the elephant is a pillar, and so on. None of them can see the elephant in its totality, and therefore none of them is able to perceive what the elephant really is. This book offers glimpses into Indias past, its present, and where it may be headed in the future. I hope that, taken together, these glimpses will give the reader a good sense of how India arrived at where it is today and what its future may hold.

I am enormously grateful to my editor at Oxford University Press (OUP) in New York, Timothy Bent, for his patience during the long period this book was put on hold. As it turned out, had the book been published on schedule before the election of Narendra Modi in 2014, it would have been almost instantly obsolete. Sincere thanks as well to Rajesh Kathamuthu at Newgen and Mariah White at OUP for their help in transforming my manuscript into a finished book.

I also wish to thank Brendan Mark Foo for his assistance with initial research for the book while an intern at the World Policy Institute in New York, as well as former Institute colleagues Michele Wucker, Belinda Cooper, Claudia Dreifus, and Kate Maloff for their early support. Thanks also to Ajith Francis, who fact-checked the draft manuscript for me in Paris.

I sincerely thank eminent India scholars Christophe Jaffrelot, Sumit Ganguly, Ananya Vajpeyi, and Ines Zupanov for their generous friendship and support throughout and for taking time from busy schedulesas also did Catherine Servan-Schreiberto read or have read anonymously, on a quick deadline, sections of the book for accuracy. I take responsibility for any errors that remain.

In addition to these scholars, this book benefited from my exchanges with my network of scholars, journalists, authors, artists, and activists with deep connections to India, many of whom I am honored to call my friends. Too numerous to cite here, I thank specially, in no particular order, Mallika Sarabhai, Basharat Peer, Ganeve Rajkotia, Neeta Gupta, Ingrid Therwath, Aliette Armel, Noopur Tiwari, Ramachandra Guha, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Rajiv Desai, Stanley Wolpert, Narendra Pachkedhe, Tridip Suhrud, Manu Bhagavan, Meena Alexander, David Lelyveld, Marina Budhos, Zette Emmons, Siddharth Dube, Ishaan Tharoor, Kanishk Tharoor, Dina Siddiqi, David Ludden, Radhika Balakrishnan, Mallika Dutt, Zeyba Rahman, Judi Kilachand, Devinder Sharma, Bndicte Manier, Sujata Parekh, Atul Kumar, Vinod Jose, Dilip dSouza, Vibha Kamat, Naresh Fernandes, Salil Tripathi, Leela Jacinto, Kavita Nandini Ramdas, Sheela Bhatt, Samir Saran, Malvika, Tejbir Singh, Mukul Kesavan, Salman Rushdie, Barkha Dutt, Amitav Ghosh, Shashi Tharoor, Sooni Taraporewala, and Thrity Umrigar.