Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

African American children are not without history, though discussions about them are often ahistoricalas though the children just arrived on the educational scene in the 1970s with nothing but a plethora of problems.

VANESSA SIDDLE WALKER ,

Their Highest Potential

Preface

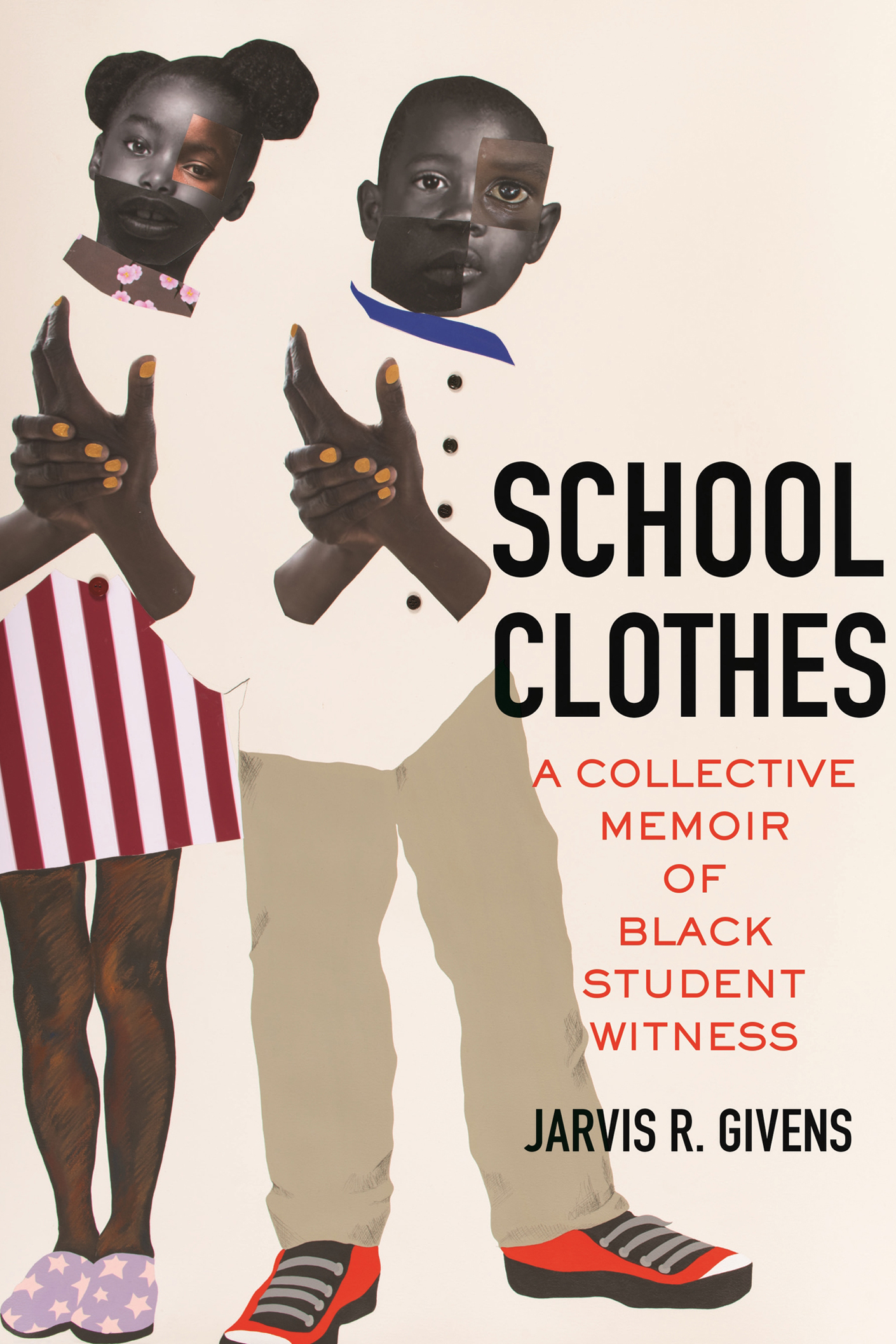

School Clothes and the Black Vernacular

I got shoes, you got shoes,

All Gods chillun got shoes;

When I get to heaven, gonna put on my shoes

And walk all over Gods heaven

I got a robe, you got a robe,

All Gods chillun got a robe;

When I get to heaven, gonna put on my robe

And shout all over Gods heaven

All Gods Chillun Got Shoes,

African American spiritual

WHEN I WAS A YOUNG STUDENT , my family referred to school clothesuniforms or clothing purchased with the specific intent of being worn to school. Shopping for school clothes before the new academic year was an occasion of major significance. If I stayed over at a cousins house between Monday and Friday, I had to pack some school clothes, just as I knew to pack some church clothes if I visited my grandmother for the weekend. When my cousins and I came home in the afternoons, we had to take off our school clothes before going outside and were usually instructed to put on some play clothes, or specifically play shoeswe were not to wear newer shoes or good shoes reserved for school or events where we had to look our best. We neednt worry about play clothes getting dirty or play shoes getting scuffed: they were already, by definition, messed up. Embedded in such routines and usage were values about school, church, and play, although this knowledge was rarely explicitly articulated.

These sartorial politics reflect distinct ways of being in African American vernacular culture, a culture held and cultivated internally, where black people expressed their own aesthetic judgments, their own ways of seeing the world, its history, and its meanings. Immediately following Emancipation, black communities all over the United States went to school as a means of putting distance between themselves and the conditions of a slave past that constantly threatened to contaminate their lives as free people. I found accounts of students dressing up for schooland for freedomin the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to be particularly beautiful and endearing.

I encountered portraits of students in the first days of freedom trying to look the part. Take E. D. Tilghman, for instance. After this formerly enslaved young man was admitted to Hampton Institute in July 1868, he asked for time to get his affairs in order. He made only $5.50 per week, but he was determined to find a way to pay for schooland the appropriate clothing! You may relie on my coming, he assured them, for I am coming without I dies or sickness prevents, as soon as I get my clothes look out for me. Black students dressed in ways that made them and their people feel proud, striving to put on attire commensurate with their mission.

More than raiment, school clothes were something akin to ceremonial garb. At least, that is how I think of it when I reflect on the black farmers near Maysville, South Carolina, who held high ambitions for one of their own: a Miss Mary Jane McLeod (Bethune). In October 1888, they halted all work operations to send a thirteen-year-old Mary Jane off to Scotia Seminary. Some gifted her with clothes for the journey. We used to have little cracker boxes. We kept our clothes in them, so my father went down and got me a little trunk, Bethune recalled. Some neighbors knitted a pair of stockings, some gave me a little linsey dress, little aprons, this that and the other, and when that October day came I can see myself now, going down to Maysville to take the train for the first time in my life. The black farmers stopped work that afternoon, got out the wagons, mules, ox-carts; some riding, some walking. They were going to Maysville to put me on the train to go to school, she recounted. Mary Jane was their proxy, a young student striving to make freedom a real thing, for herself and her people.

Bethunes story about school clothes is a favorite of mine, in part because it was the first to jump out at me. I stumbled on the anecdote while reading an interview with Bethune in the archives at Fisk University. I was supposed to be searching for Carter G. Woodson in the papers of southern black teachers and black teacher organizations for my first book, Fugitive Pedagogy. But as always, my mind started wandering around in the archive. And such wandering often leads to me wondering about new questions, new traces; often I see things that have nothing to do with what I am searching for, but I find myself unable to turn away from them. After sitting with Bethunes story of those black farmers stopping work to send her off to school and providing her with new clothes, as well as her descriptions of the particular articles of clothing, I decided to take what I had seen with me. My eye would catch more and more sartorial metaphors in black student narratives. Such stories appear post-Emancipation, but they are intimately connected to African American experiences during slavery.

School clothes became part and parcel of African Americans efforts to undo the harms inflicted on black youth during slavery and its afterlives. A young Booker T. Washington helps elucidate this point. Washington named the wearing of a flax shirt as the most trying ordeal he endured as a slave boy in Virginia. He explained, It was common to use flax as part of the clothing for the slaves. That part of the flax from which our clothing was made was largely the refuse, which of course was the cheapest and roughest part. Washington detailed his memory of that dreadful slave shirt: I can scarcely imagine any torture, except, perhaps, the pulling of a tooth, that is equal to that caused by putting on a new flax shirt for the first time. It is almost equal to the feeling that one would experience if he had a dozen or more chestnut burrs, or a hundred small pin-points, in contact with his flesh.... The fact that my flesh was soft and tender added to the pain. To mitigate the pain of that awful shirt, Washingtons older brother John performed one of the most generous acts he had ever heard of one slave relative doing for another. Whenever Booker was forced to wear a new flax shirt, John offered to wear it first, for several days, until the shirt was broken in. Washington was about nine years old when slavery ended, but this experience did more than mark his flesh. The memory left an impression on him.

Black youth like Tilghman, Bethune, and Washington covered themselves in new clothes to go to school after Emancipationoften with the care of parents and communityseeking redress for the stolen childhoods of years past, as historian Wilma King described the realities of enslaved youth. School clothes were often armor, forms of protection just as much as assertions of dignity and self-worth for young black people whose childhoods continued to be threatened, even after slavery was legally abolished.

Quite often, black learners were elaborately adorned, with decorations on the decorations, to borrow from Zora Neale Hurston. Black students will to adorn was a disruptive force, challenging past and present threats seeking to violate their dignity, as learners and as human beings.