A mericans All

Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture

A mericans All

Good Neighbor Cultural Diplomacy in World War II

Darlene J. Sadlier

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

The publication of this book was supported in part by Ambassador and Mrs. Keith L. Brown.

Copyright 2012 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2012

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

utpress.utexas.edu/about/book-permissions

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sadlier, Darlene J. (Darlene Joy)

Americans all : good neighbor cultural diplomacy in World War II / by Darlene J. Sadlier. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-73930-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. United StatesRelationsLatin America. 2. Latin AmericaRelationsUnited States. 3. World War, 19391945Diplomatic history. 4. United StatesCultural policy. 5. United StatesForeign relations19331945. 6. United StatesIntellectual life20th century. 7. Cultural industriesPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 8. Popular culturePolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. I. Title.

F1418.S16 2012

327.730809 04dc23 2012020602

ISBN 978-0-292-73931-4 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-74980-1 (individual e-book)

For JAMES NAREMORE and in memory of ROBERT W. SADLIER

C ontents

1.

The Culture Industry Goes to War

2.

On Screen

3.

On the Air

4.

In Print

5.

In Museums, in Libraries, and on the Home Front

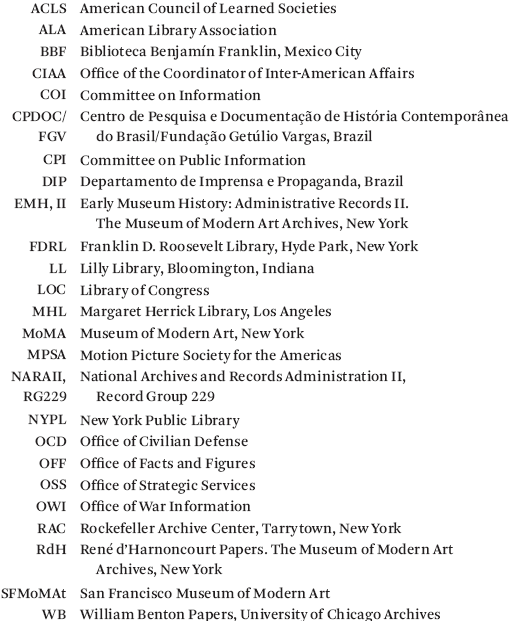

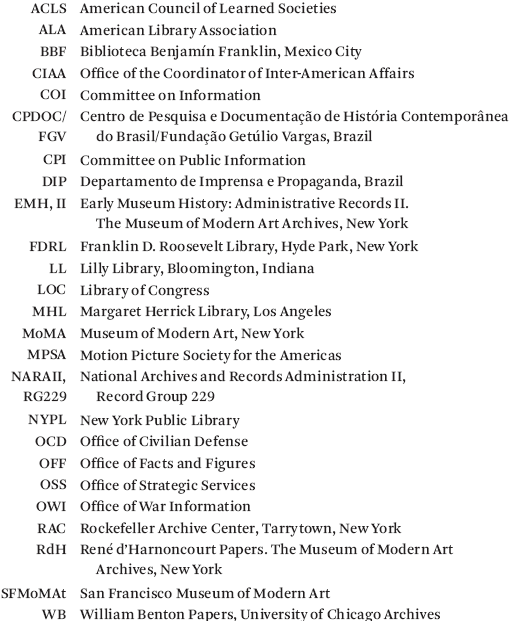

Abbreviations

Acknowledgments

Productive archival research depends greatly upon the knowledge and helpfulness of library specialists, who not only train us in the art of using collections but also frequently point us to little-known treasure troves of information. Research for this book took me to more than a dozen archives beginning several years ago with a visit to the Margaret Herrick Library in Los Angeles and ending with a second visit to the National Archives II in College Park, Maryland. Stops between those places included collections at the University of Louisiana; the University of Texas at Austin; the University of Chicago; the University of California Los Angeles; the Library of Congress; the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York; the Museum of Modern Art; the New York Public Library; the Rockefeller Archive Center in Tarrytown, New York; and the Fundao Getlio Vargas in Rio de Janeiro. I also greatly benefited from holdings at Indiana Universitys Lilly Library and Presidential Archive of Herman B. Wells. Special thanks go to Latin American specialist Becky Cape at the Lilly Library, Katherine D. McCann and Jan Grenci at the Library of Congress, Jean Kiesel at the University of Louisiana, Martha Harsanyi at Indiana University, Carol Radovich at the Rockefeller Archive Center, and Barbara Hall at the Margaret Herrick Library.

I was fortunate to receive a number of grants to support my research, including fellowships from Indiana Universitys College of Arts and Humanities Institute, Office of the Vice Provost for ResearchNew Frontiers in Arts and Humanities, Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, and Office of the Vice President for International Affairs. A Rockefeller Archive Center Fellowship supported my research there. Along with grants, I want to single out the support and friendship of Gisela Cramer and Ursula Prutsch, whose work on the National Archive II files on the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA) was invaluable.

Anthony N. Doob at the University of Toronto was extremely generous in providing me with the personal papers of his father, Leonard W. Doob, who was Nelson Rockefellers public opinion adviser in the first years of the CIAA. Sam Bryan was always graciously attentive to my queries about his father, Julien Bryan, who made close to two dozen 16 mm educational films for the CIAA. I was also pleased to correspond with Ted Thomas, whose father, Frank Thomas, was one of Walt Disneys most talented artists. Teds documentary Walt and El Grupo (2009) provides important additional evidence of the CIAAs promotion of the Good Neighbor. Brazilianist and World War II historian Frank D. McCann provided me with generous detailed feedback on early chapters of the book. I also benefited greatly from suggestions by Nicholas J. Cull, whose writings on U.S. public diplomacy were inspirational. Julie Maguire of the Brett Weston Archives and Barbara Rominski of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art allowed me to include Westons 1940 photograph of Grace McCann Morley, who worked closely with the CIAA on traveling art exhibits. Lauren Post, great-granddaughter of U.S. cartoonist Rollin Kirby, gave me permission to include his Good Neighbor cartoon. At the University of Texas Press, I am especially grateful to Theresa May, who initially encouraged this project, and to Jim Burr, who has been a wonderful editor.

Although the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration is not part of my personal history, the 1930s and especially the 1940s hold a special interest for me. This period was one of the few times in U.S. history when cultures importance in domestic and world affairs was recognized and discussed alongside issues of finance and commerce. Having a loving and highly knowledgeable companion who has written extensively about the 1940s and who contributed to the chapters in this volume made the book all the more exciting and enjoyable to write. The book is dedicated to him and to the memory of my father, who was a U.S. infantry soldier in North Africa and Europe during World War II.

INT RODUCTION

Cultural diplomacy, including what Joseph S. Nye in 1990 described in slightly broader terms as soft power, has never been completely absent from U.S. foreign policy, though it has rarely been given major emphasis.

Fortunately, if the recent surge in publications, national and international conferences, and websites on the topic is any measure and if the nations move at the time of this writing toward greater dialogue and face-to-face negotiation is symptomatic of things to come, cultural diplomacy is likely to show signs of renewal and health. There continues to be debate about the means and ends of such diplomacy, questioning the idea that it automatically leads to better international relations; nevertheless, the evidence suggests that the U.S. image both regionally and worldwide has rarely been more positive than when cultural or public diplomacy at its best is part of the foreign policy mix.

The present study moves back in time to the most fully developed and intensive use of soft power in U.S. history: Nelson A. Rockefellers Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA, 19401945), one of the first U.S. government agencies specifically created to enact a large-scale cultural diplomacy initiative. In what follows, I offer the first in-depth study of the CIAAs wide-ranging, ambitious plan to persuade all Americans of their common wartime cause.

A brief history of key terms may be of use at the outset. The word culture has had a number of meanings and originally signified religious worship, together with cultivation of crops and farm animals and artificial development of microscopic organisms. The sixteenth century saw an anthropocentric shift in usage to denote the development of the mind, faculties, and manners. By the nineteenth century, culture was synonymous with civilization and connoted a particular form of intellectual development. In the second half of the twentieth century, Raymond Williams divested the term of romantic, lofty implications and argued that it should be used to describe not simply high culture but also a particular way of life (

Next page