The Nature and Scope of Bioethics

Bioethics as a field is relatively new, emerging only in the late 1960s, though many of the questions it addresses are as old as medicine itself. When Hippocrates wrote his now famous dictum Primum non nocere First, do no harmhe was grappling with one of the core issues still facing human medicine todaynamely, the role and duty of the physician. With the advent of late twentieth-century science, an academic field emerged to reflect not only on the important and age-old issues raised by the practice of medicine but on the ethical problems generated by rapid progress in technology and science. Forty years after the emergence of this field, bioethics now reflects the profound changes in medicine and the life sciences.

Against the backdrop of advances in the life sciences, the field of bioethics has a threefold mission: to raise important questions about the general practice of medicine and the institutions of health care in the United States and other economically advanced nations, to wrestle with the novel bioethical dilemmas constantly being generated by new biomedical technologies, and to challenge the presumptions of international and population-based efforts in public health and the delivery of health to economically underdeveloped parts of the globe. While attention to the ethical dilemmas accompanying the appearance of new technologies such as stem cell research or nanotechnology can command much of the popular attention devoted to the field, the other missions are of equal importance.

At the core of bioethics are questions about medical professionalism, such as What are the obligations of physicians to their patients? and What are the virtues of the good doctor? Bioethics explores critical issues in clinical and research medicineincluding truth telling, informed consent, confidentiality, end-of-life care, conflicts of interest, nonabandonment, euthanasia, substituted judgment, rationing and access to health careand in the withdrawal and withholding of care. Only minimally affected by advances in technology and science, these core bioethical concerns remain the so-called bread-and-butter issues of the field.

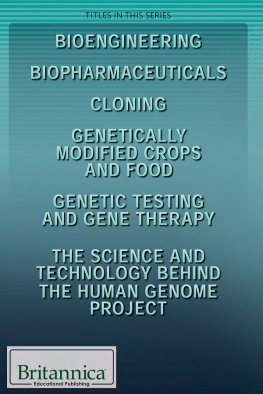

The second mission of bioethics is to enable ethical reflection to keep pace with scientific and medical breakthroughs. With each new technology or medical breakthrough, the public finds itself in uncharted ethical terrain that it does not know how to navigate. In what is very likely to be the century of biology, there will be in the twenty-first century a constant stream of moral quandaries as our scientific reach exceeds our ethical grasp. As a response to these monumental strides in science and technology, the scope of bioethics has expanded to now include the ethical questions raised by the human genome project, stem cell research, artificial reproductive technologies, the genetic engineering of plants and animals, the synthesis of new life forms, the possibility of successful reproductive cloning, preimplantation genetic diagnosis, nanotechnology, and xenotransplantation, to name only some of the key recent advances.

Bioethics has also more recently begun to engage with the challenges posed by delivering care in underdeveloped nations. Whose moral standards should govern the conduct of research to find therapies or preventive vaccines useful against malaria, HIV, or Ebolalocal standards or Western principles? And to what extent is manipulation or even coercion justified in pursuing goals such as the reduction of risks to health care in children or the advancement of national security? This population-based focus raises new sorts of ethical challenges both for health care providers who seek to improve overall health indicators in populations and for researchers who are trying to conduct research against fatal diseases that are at epidemic levels in some parts of the world.

As no realm of academic or public life remains untouched by pressing bioethical issues, the field of bioethics has broadened to include representation from scholars in disciplines as diverse as philosophy, religion, medicine, law, social science, public policy, disability studies, nursing, and literature.

The History of Bicethics

Bioethics as a distinct field of academic study has only existed for forty years, and its history can be traced back to a cluster of scientific and cultural developments in the United States in the 1960s. The catalyst for the creation of the interdisciplinary field of bioethics was the extraordinary advances in American medicine coupled with radical cultural changes during this time period. Organ transplantation, kidney dialysis, respirators, and intensive care units made possible a level of medical care never before attainable, but these breakthroughs also raised daunting ethical dilemmas that the public had never previously been forced to face, such as when to initiate admission to an ICU or when treatments such as dialysis could be withdrawn. The advent of the contraceptive pill and safe techniques for performing abortions added to the ethical quandaries of the new medicine. At the same time, cultural changes placed a new emphasis on individual autonomy and rights, setting the stage for greater public involvement and control over medical care and treatment. Public debates about abortion, contraceptive freedom, and patient rights were gaining momentum. In response, academics began to write about these thorny issues, and scholars were beginning to view these applied ethics questions as the purview of philosophy and theology. Bioethicsor, at the time, medical ethicshad become a legitimate area of scholarly attention.

In its early years, the study of bioethical questions was undertaken by a handful of scholars whose academic home was traditional university departments of religion or philosophy. These scholars wrote about the problems generated by the new medicine and technologies of the time, but they were not part of a discourse community that could be called an academic field or subject area. Individual scholars, working in isolation, began to legitimize bioethical issues as questions deserving rigorous academic study. But bioethics only solidified itself as a field when it became housed in institutions dedicated to the study of these questions. Academic bioethics was born with the creation of the first bioethics center.

Ironically, academic bioethics came into existence through the creation of an institution that was not part of the traditional academy. The first institution devoted to the study of bioethical questions was a freestanding bioethics center, purposely removed from the academy with its rigid demarcations of academic study. The institution was the Hastings Center, originally called A Center for the Study of Value and the Sciences of Man, which opened its doors in September 1970. Its founder, Daniel Callahan, created the Hastings Center to be an interdisciplinary institute solely dedicated to the serious study of bioethical questions. Callahan, a recently graduated Ph.D. in philosophy, had been one of the isolated scholars working on an issue in applied ethics, and he had found himself mired in complex questions that took him far afield from the traditional boundaries of philosophy. His topic, abortion, required engagement with the disciplines of law, medicine, and social science, which he felt himself unprepared to navigate. With academic departments functioning as islands within a university, it seemed that truly interdisciplinary work was impossible. The Hastings Center was founded to create an intellectual space for the study of these important questions from multiple perspectives and academic areas.