Meral Beksa (ed.) Methods in Molecular Biology Methods and Protocols Bone Marrow and Stem Cell Transplantation 2nd ed. 2014 10.1007/978-1-4614-9437-9_1

Springer Science+Business Media, New York 2014

1. Reporter Gene Technologies for Imaging Cell Fates in Hematopoiesis

Sophie Kusy 1 and Christopher H. Contag 1

(1)

Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Abstract

Advances in noninvasive imaging technologies that allow for in vivo dynamic monitoring of cells and cellular function in living research subjects have revealed new insights into cell biology in the context of intact organs and their native environment. In the field of hematopoiesis and stem cell research, studies of cell trafficking involved in injury repair and hematopoietic engraftment have made great progress using these new tools. Stem cells present unique challenges for imaging since after transplantation, they proliferate dramatically and differentiate. Therefore, the imaging modality used needs to have a large dynamic range, and the genetic regulatory elements used need to be stably expressed during differentiation. Multiple imaging technologies using different modalities are available, and each varies in sensitivity, ease of data acquisition, signal to noise ratios (SNR), substrate availability, and other parameters that affect utility for monitoring cell fates and function. For a given application, there may be several different approaches that can be used. For mouse models, clinically validated technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) have been joined by optical imaging techniques such as in vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) and fluorescence imaging (FLI), and all have been used to monitor bone marrow and stem cells after transplantation into mice. Photoacoustic imaging that utilizes the sound created by the thermal expansion of absorbed light to generate an image best represents hybrid technologies. Each modality requires that the cells of interest be marked with a genetic reporter that acts as a label making them uniquely visible using that technology. For each modality, there are several labels to choose from. Multiple methods for applying these different labels are available. This chapter provides an overview of the imaging technologies and commonly used labels for each, as well as detailed protocols for gene delivery into hematopoietic cells for the purposes of applying these specific labels to cell trafficking. The goal of this chapter is to provide adequate background information to allow the design and implementation of an experimental system for in vivo imaging in mice.

Introduction

In vivo imaging of labeled transplanted cells has made it possible to observe cell movement and to visualize cell function over time in the intact animal. Previous techniques have required sacrificing animals in order to analyze specific tissues and tissue compartments of interest for the presence of the rare labeled cells. Although these sorts of analyses certainly have yielded valuable information, their two major limitations are (1) each animal can only be analyzed at a single time point and (2) tissues of interest must be preselected such that potentially informative data on cell trafficking in other regions is lost. Alternatively, biopsies can be taken to address the first limitation; however, the second limitation remains. Sampling limitations exist for all ex vivo assays, and the lack of temporal information can introduce biases into a study. Therefore, a number of investigators have been developing and advancing novel noninvasive imaging approaches that can be performed repeatedly in a given animal over time. The use of such approaches in our group has revealed features of biological processes that were unexpected including the apparent tropism of Listeria monocytogenes to the lumen of the gall bladder, an otherwise sterile environment [). These types of discoveries are only possible because of the ability to make longitudinal observations of the whole mouse after the transfer of labeled cells.

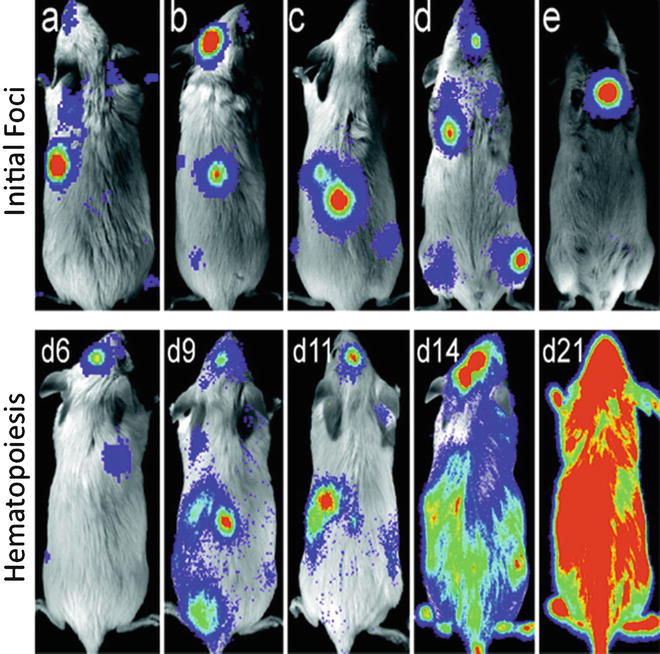

Fig. 1

Location of bioluminescent foci following transplantation of transgenic luc+ hematopoietic stem cells. Foci were apparent in individual animals at anatomic sites corresponding to the location of the spleen, skull, vertebrae, femurs, and sternum ( a e , respectively) at 69 days after transfer. The patterns of engraftment were dynamic with formation and expansion or formation and loss of the bioluminescent foci. One recipient of 250 HSCs that was monitored over time is shown ( second row ). In this animal, two initial foci were apparent on day 6. By day 9, one was no longer detectable and another remained at nearly the same intensity as on day 6. New foci were apparent on day 9, and then the intensity at these sites weakened or disappeared by day 11. Pseudo-colored images reflecting optical signal intensity are overlaid upon a gray scale reference image of the animal. (Reproduced from Ref. [], with permission)

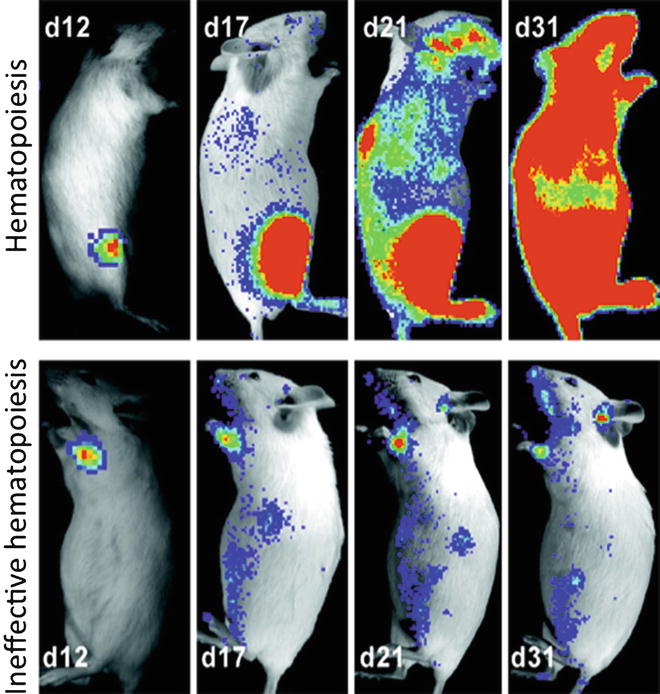

Fig. 2

Temporal analyses of hematopoiesis following single cell transplants. These mice demonstrate the variability in contribution to reconstitution that was observed following the establishment of initial foci of hematopoietic engraftment after transplantation of single transgenic luc+ hematopoietic stem cells. Pseudo-colored images reflecting optical signal intensity are overlaid upon a gray scale reference image of the animal. (Reproduced from Ref. [], with permission)

A number of powerful imaging techniques have been described and are now being used to understand when, where, and which cells move, in many different mouse models of human biology and disease, and what cells do under a given set of circumstances. Imaging has been applied to the study of injury repair, infectious processes, host response to infection, hematopoietic reconstitution, tumor vascularization, response to chemotherapy, and antitumor immune response. This chapter will focus on the labeling and imaging of murine bone marrow cells for the purpose of transplantation and analysis using in vivo imaging technologies. These types of studies can serve as a demonstration of how imaging can improve the study of biology and reveal the nuances of complex biological processes and the subtlety of therapeutic responses.

1.1 Imaging Modalities

Several imaging modalities have been used for the investigation of stem cell fates and function, and a number of useful tools have been developed by each of these []. There are a number of additional optical imaging approaches that have been developed for sensing and imaging in the living body, including diffuse optical tomography (DOT) and optical coherence tomography (OCT), but only in vivo BLI and fluorescence have been used to study long-term cell trafficking patterns, and these are amenable to reporter gene approaches. Despite the strengths of each of the available imaging modalities, the relatively greater accessibility, ease of use, and throughput capabilities have contributed greatly to the widespread use of BLI for animal studies. BLI is now routinely used as an initial step in the development of novel cell transfer protocols, and once the efficacy of the protocol is established, the BLI data serve as a guide for its adaptation into the clinic. Clinically, however, useful imaging modalities do not typically include optical imaging approaches.