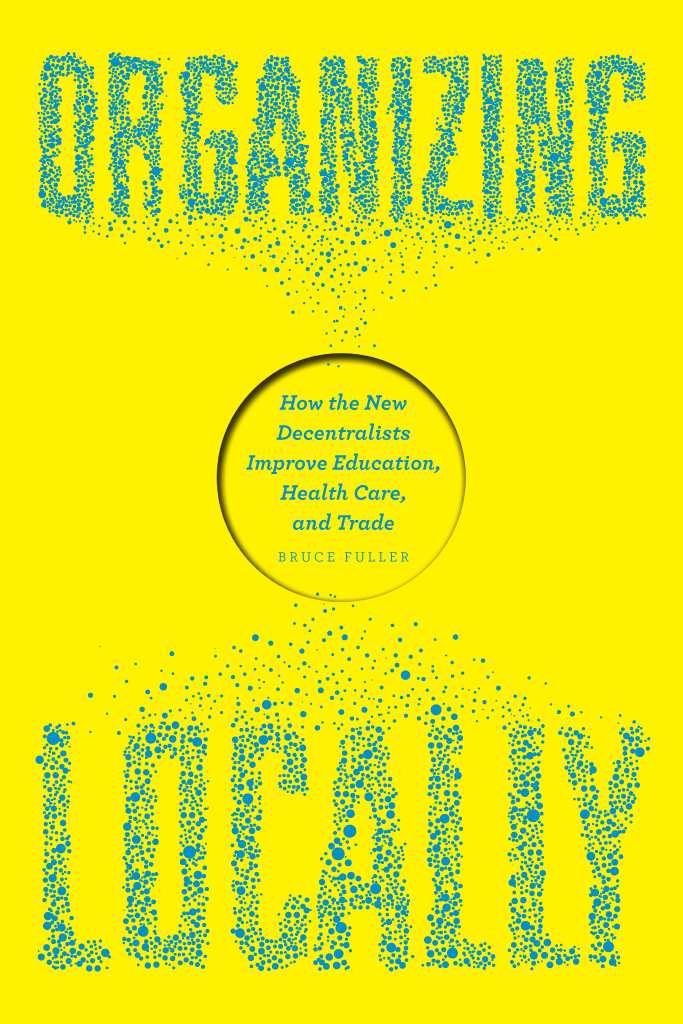

Bruce Fuller is professor of education and public policy at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of Growing Up Modern, Government Confronts Culture, Inside Charter Schools, and Standardized Childhood. His writings appear in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Commonweal.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2015 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-24640-6 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-24654-3 (paper)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-24668-0 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226246680.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fuller, Bruce, author.

Organizing locally : how the decentralists improve education, health care, and trade / Bruce Fuller ; with Mary Berg, Danfeng Soto-Vigil Koon, and Lynette Parker.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-24640-6 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-226-24654-3 (paperback : alk.) ISBN 978-0-226-24668-0 (e-book) 1. Decentralization in governmentUnited States. 2. Community organizationUnited States. 3. Health services administration. 4. Community banks. 5. Charter schools. I. Title.

HM 766. F 85 2015

352.2'83dc23

2014031547

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

with Danfeng Soto-Vigil Koon

with Mary Berg

with Lynette Parker

Society and human fellowship will be best served if we confer the most kindness on those with whom we are most closely associated.

CICERO , Athens, 44 BC

If we are to have peace on earth, our loyalties must become ecumenical, our loyalties must transform our race, our tribe, our class.

MARTIN LUTHER KING , Georgia, 1967

Deinstitutionalization is associated not only with the growing recognition that current institutional patterns are ineffective, but also with the development of a challenging alternative institutional logic.

W. RICHARD SCOTT , Stanford, California, 2000

Organizing Locally, as the Center Folds

You may not recallespecially if under fortythat massive and vibrant institutions once animated modern society. American factories stamped out cars, magically wove elegant wardrobes, even crafted those cool stereo systems our parents coveted, tucked into sleek wooden cabinets. The efficiency of manufacturers, going back a century and a half, pushed prices lower for a breathtaking array of goods, from radios to washing machines. This, along with rising wages, would kindle a burgeoning middle class and seem to validate the wisdom of smug management scientists; human labor and social cooperation was best orchestrated by central engineers and leaders of public institutions, bent on standardized products, efficiency, and a tidy set of moral guideposts.

Modern governmenteager to mimic the factorys humming routines and uniform productsbuilt expansive school plants, universities for the masses, huge hospitals, and a benevolent bureaucracy that lent order to economic and social life. A confident postwar America stretched out tentacles of interstate highways across the land, the grandest project ever undertaken by any civilization. You may even recall a nationwide network of spotless and well-staffed post offices? Through a childs eyes in the mid-twentieth century, Walt Disneys Tomorrowland was magically rising up around us, during this apex of modernity.

Almost two generations ago, top-heavy firms and feckless public institutions found themselves on the ropes, beset by lagging performance and fading legitimacy, now seen as potent only in eroding the human spirit. Our manufacturers suffered a first jolt of competition from East Asia in the 1970s, then from even lower wages in developing nations, falling into steady decline. America was no longer the marketplace at which the world shopped. Rust crept over the once shiny industrial machine, like an old engine discarded on a damp lot. Decrepit iron foundries that once cast and exported steel beams around the globe now sat empty. Cavernous auto plants lay abandoned on vast tracts, from Detroit to Los Angeles, enveloped by prickly weeds pushing up through cracked concrete, where rows of brightly painted cars with that scent of fresh Naugahyde once sat.

As the factory faltered, popular worry grew over the efficacy of creaky public institutions as wellfirst from the political Right, then from the Leftbe it the nations stumbling public schools or uneven quality and high cost of health care. This invited political leaders to attack (their own) state-run organizations, aiming to exact greater efficiency or less government spending. Central regulation of teachers or physicians, and single mothers on welfare, was to advance greater accountability for individuals and institutions alikethat tough love that Bill Clinton first doled out.

Better yet, why not infuse public institutions with a stiff dose of market competition; after all, it is a grassroots version of direct accountability between firm and client. The Reagan White House would embolden conservatives by awarding portable vouchers to parents to shop for allegedly better, even sectarian, schools, or for day care and housing in the 1980s. They brought price competition to health-care providers and even contracted with for-profit companies to run prisons. Civic spaces were no longer energized by social ideals and shared aspirations. Instead, the public commons became a contested ground for self-interested individuals or firms to pursue their particular interests; competition for clients was to magically lift the quality and productive efficiency of schooling, housing, or health care.

Corporate faith in hierarchy and top-down management waned as well. The factory model and its assembly-line jobs were packed up and moved offshore. Factories soon became an antiquated way to organize work stateside. Californias sunny and sleek high-tech industry, powered by inventive thinkers and sandal-clad software writers, arose in stark counterpoint to stodgy manufacturers of the Rust Belt. The control of capital and major design decisions may remain centralizedas with Apple Computer or clothier Levi-Straussbut the hierarchical organization chart and routinized labor made a steady exit overseas. And the value-added bonus now enjoyed by avant-garde companies stemmed from creative design and innovative code, bubbling up from down below, given shape by creative collaborators inside posthierarchical firms.

So its no surprise that a variety of efforts to deinstitutionalizeto decenter who controls work, divvies up resources, and engages students, patients, or clients on the groundhave spread across public and private spheres over the past half century. Political and corporate leaders alike now rally around the idea of disassembling hierarchies, like a child eagerly toppling a castle of Legos only to piece together tiny yet colorful huts across the floor. Turns out that small may indeed be beautiful.