Also by John Matteson

EDENS OUTCASTS:

THE STORY OF LOUISA MAY ALCOTT

AND HER FATHER

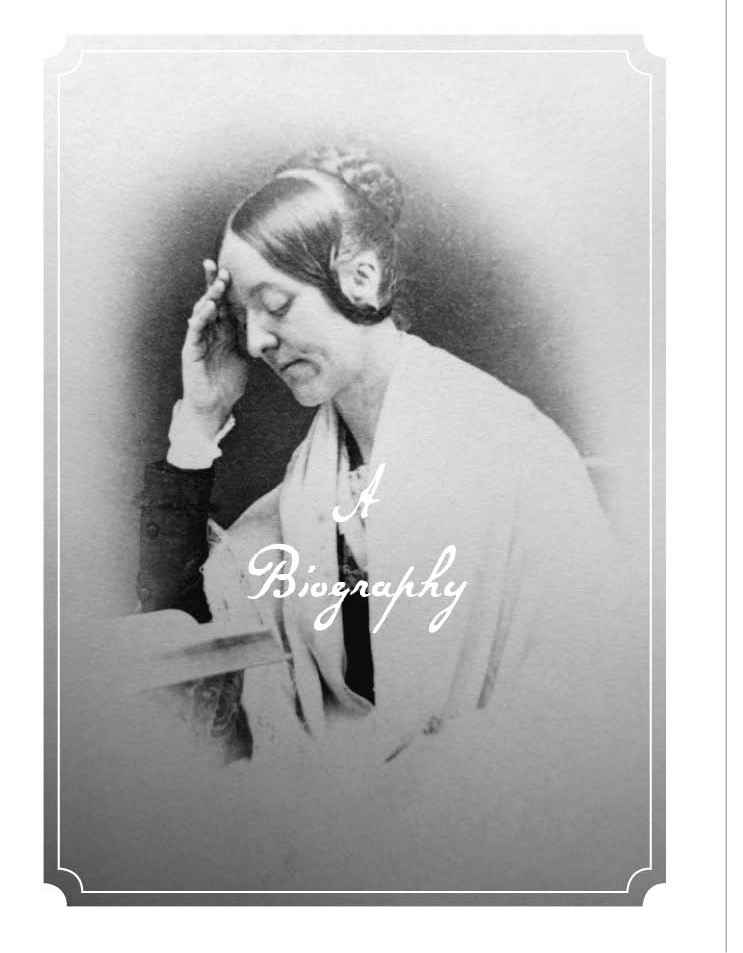

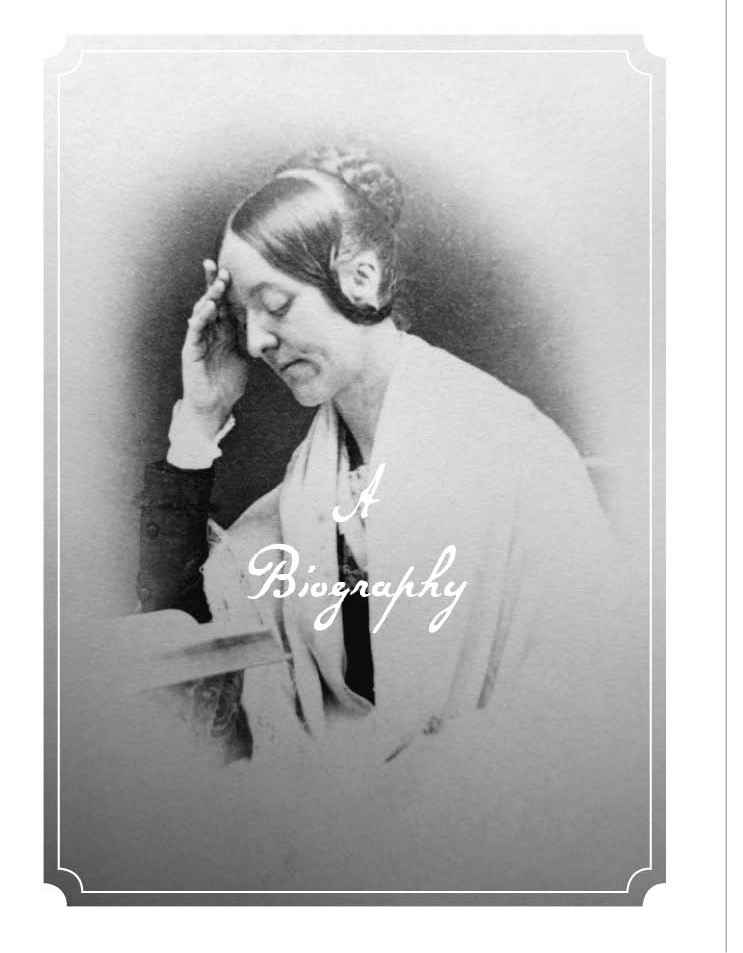

FRONTISPIECE : On the same day that Fuller sat for what has long been presumed to be the only photographic image of her, daguerreotypist John Plumbe also took this second exposure. It is now published for the first time.

( COURTESY OF KENT BICKNELL )

W ith deepest appreciation for all they have done to encourage the study of woman in the nineteenth century, this book is gratefully inscribed to Joel Myerson and to the memory of Madeleine B. Stern.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

How can you describe a Force?

How can you write the life of Margaret?

S AMUEL G RAY W ARD

T HINK FIRST OF ENDINGS.

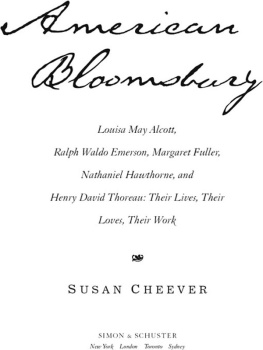

Margaret Fuller was, in her time, the best-read woman in America and the one most renowned for her intelligence. She was the leading female figure in the New England movement known as transcendentalism. She edited the first avant-garde intellectual magazine in America. She was the first regular foreign correspondent, male or female, for an American newspaper. As a literary critic, she was rivaled in her era only by Edgar Allan Poe. Three years before the convention that is usually regarded as the beginning of the womens rights movement in the United States, she wrote a groundbreaking book demanding legal equality for women. And yet, if the ordinary person today knows only one thing about Margaret Fuller, that particle of knowledge is likely not to concern any of her achievements, but how her life came to an end.

At the age of only forty, having spent almost three and a half years in Europe as foreign correspondent for the New-York Tribune , Fuller sailed back to America to begin a new life with the husband she had met in Rome, Marchese Giovanni Ossoli, and their young son, Angelino. That new life never began. On July 19, 1850, within sight of land, the ship on which the Ossolis were traveling struck a sandbar off the coast of Fire Island, New York, and, in the midst of a fierce and unseasonable hurricane, broke apart and sank. Though most of the people on board managed to reach the shore alive, none of the Ossolis survived. This was how Margaret Fuller became ingrained in our history: not as the sparkling conversationalist enlivening Ralph Waldo Emersons study or the bookstores of Boston with her wit and erudition; not as the impromptu military nurse giving aid and encouragement to freedom fighters who had fallen in the streets of Rome defending their new republic; not even as the accomplished and dedicated scholar churning out a stunning body of literary criticism and social commentary; but as a forlorn and exhausted figure beside a broken mast, her hands on her knees, clad only in a soaked-through nightgown, soon to feel the wave that would thrust her overboard and into eternity.

Fullers drowning was a monstrosity of ill fortune. In order for it to happen, it required navigational incompetence, a freak hurricane, and the nearly criminal indifference of at least thirty eyewitnesses. Yet the bizarrely improbable wreck became the defining anecdote of Fullers life, propelling her almost immediately into the realm of morbid legend. Prematurely silenced, she wasand she remainsthe mysterious, presiding ghost of American transcendentalism.

The tragedy of such an early and senseless death resides not only in the death itself. It lies also in the way that the death comes to be perceived as the lifes most relevant fact, even as its inevitable outcome. The shattering nature of Fullers demise threatens to reduce all that preceded itno matter how unique, affirming, or triumphantto a mere prologue to the closing catastrophe. The way we view such a death is paradoxical. On the one hand, it is the incongruity of such a death that makes it linger in our minds; we remember it because it is so clearly not the obvious or deserved outcome of the life that preceded it. On the other, because we need for stories to make sense, we find ourselves reacting as if the tragedy had to happen, and this bizarre conviction of inevitability transforms the absurd into the inescapable. If we are not careful, the victims death can easily blight and darken all that he or she did or stood for. We struggle to preserve in our minds how James Dean looked before he climbed into his Porsche on that late September day, the fateful serenity of Martin Luther King as he marched through Memphis, or the boyish smile of Robert Kennedy as he flashed a peace sign and left the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel. We want to keep such people as they were, full of hope, life, and the thrill of new possibilities. The effort to do so is always futile. Still, it must be attempted, lest we conclude that our own strivings are empty of meaning, since they, too, can be erased in a moment by happenstance and fate. To attempt the biography of a person of energy, resolve, and unfulfilled promise is to engage in a fantasy of rescue and resurrection.

Yet, as even Fullers first biographers were aware, restoring her to life is a daunting task, because her life was so multifaceted. She lived richly in a myriad of dimensions, leaving deep impressions on those who knew her. Though her health was chronically frail, she embodied a kind of power that defies reduction to the printed page. Moreover, to a degree far greater than any other member of her social and literary circle, Fuller possessed a genius for the reinvention of self. With a tremendous awareness of what she was doing, Fuller lived her life as an ongoing occasion for growth and change.

Fuller biographers must resist the temptation to seize a particular moment in her long development, to espouse the Fuller of that particular moment as their Margaret Fuller, and to put aside her other incarnations if they inconveniently complicate the story. Because the very essence of Fuller was her changeabilityshe referred to herself as a chameleonno single snapshot can suffice. Deliberately and intentionally, she proved them wrong, continually willing herself into different roles and reinventions.

Fullers penchant for shape shifting was a matter not only of situation but also of philosophy. In her late teens and early twenties, Fuller eagerly absorbed the Romantic ideas that she found in the works of Goethe, Novalis, and Schelling, all of whom told her that the world itself was gradually evolving toward a higher plane of consciousness and to a better approximation of perfection. She came to believe that, for an earnest soul, to rise continually toward the celestial was a matter not just of destiny but of quasi-religious duty. She believed that a human life, properly lived, ought constantly to alter itself in its quest for a higher level of self-knowledge. In Goethes Faust , she read the promise of the angels: For him whose striving never ceases / We can provide redemption, and through her ceaseless striving, Margaret Fuller sought to save herself. She strove to make of herself a fully realized soul, both intellectually complete and all-encompassing in its sympathies. To say that Margaret Fullers greatest creation was her life may come perilously close to clich, but it is true.

Next page