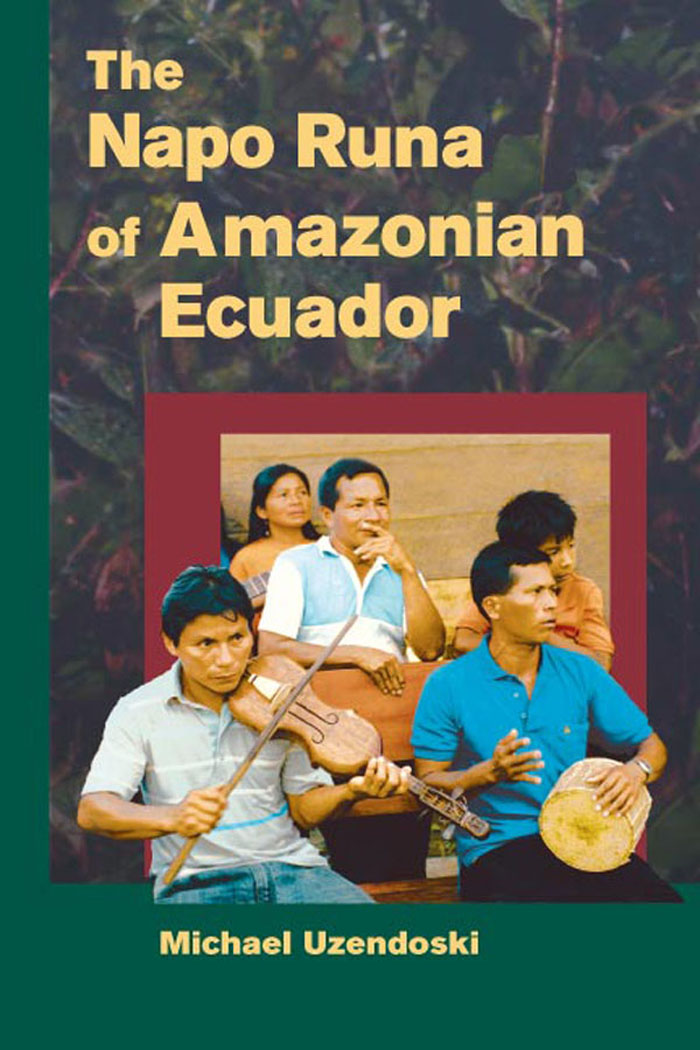

The Napo Runa

of Amazonian Ecuador

Interpretations of Culture in the New Millennium

Interpretations of Culture in the New MillenniumNorman E. Whitten Jr., General Editor

A list of books in the series appears

at the end of the book.

The Napo Runa of Amazonian Ecuador

Michael Uzendoski

University of Illinois Press Urbana and Chicago

For Edith and Sisa

2005 by Michael Uzendoski

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Uzendoski, Michael, 1968

The Napo Runa of Amazonian Ecuador / Michael Uzendoski.

p. cm. (Interpretations of culture in the new millennium)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-252-03007-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0-252-07255-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Quechua IndiansNapo River Valley (Ecuador and Peru)

Social life and customs. 2. Quechua IndiansNapo River Valley

(Ecuador and Peru)Government relations. 3. Indians, Treatment

ofNapo River Valley (Ecuador and Peru) 4. Napo River Valley

(Ecuador and Peru)Ethnic relations. 5. Napo River Valley

(Ecuador and Peru)Social life and customs. I. Title. II. Series.

F2230.2.K4U94 2005

305.898'32308664l6dc22 2005002627

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Figures

Plates

Preface

This book, written in the humanistic tradition, addresses the interrelated problems of value, kinship, and historicity among the Napo Runa. In my struggle to convey these multifaceted anthropological problems, I have drawn on the work of the late Quechua writer, poet, and anthropologist Jos Mara Arguedas. Indigenous characters in Arguedass works define themselves as spiritual-cosmic beings who are connected to the world, and especially nature, through an intense affectivity and aesthetic. These relations are not superstition but rather modes of perception by which people visualize their connections to the substances and powers of mythical forces that are essential to the materiality of things and to social process.

In thinking about Arguedass work, I have become more cognizant of the aesthetics of power in Napo, an aesthetics that cannot be divorced from the processes by which power comes to be embodied. Personhood in Napo, as I will show, is defined by experiencing flows of power that derive from realities outside oneself. The Napo Runa define power as ushai but use other terms to describe it as well: yachai (knowledge), causai (life force), samai (breath or soul substance), and urza (force). The Runa describe especially powerful people as sinzhi, or strong. Such people are especially skilled in eliciting ushai through their connections to ancestors, shamans, animals, the forest, and other powerful beings.

I also seek, however, to convey some of the subtle and complex dynamics by which ushai becomes a collective force of social action and historical consciousness. In this regard, I draw on the term millennial as it is developed in the recent volume Millennial Ecuador: Critical Essays on Cultural Transformations and Social Dynamics (2003), edited by Norman Whitten. I follow Whittens use of millennial as an English metaphor for the Quichua concept of pachacuticnamely, transformation defined as the return of space-time (chronotope) of a healthy past to that of a healthy future (Whitten 2003: x). In this reference to pachacutic, millennial events derive from the flow of ushai, the underneath or chthonic power that gives life to them.

I offer this dialectical tandem of power and transformation as an orienting tool to help readers appreciate the books larger context. I spend the first six chapters presenting the symbolic, social, and material complexities of personhood as created and defined by the Napo Runa life cycle. This is ushai, power. The final chapter changes voice, for there I consider the millennial person in the context of a significant political and historical event of change, the indigenous uprising of 2001. As I will demonstrate, the events of 2001 were monumental for the Napo Runa. Not only did they lead to several casualties, but the significance of these events has created a flow of life force and memory from the past into the future. This is the pachacutic, the transformation.

Acknowledgments

Fieldwork for this project was supported by grants from the Fulbright Institute for International Education (1994), the Research Enablement Program (OSMC) under the Pew Charitable Trusts (199697), and the University of Virginia (1999) and by a teaching and research position with the Direccin Bilinge Intercultural de Napo (199697). Subsequent trips to Ecuador were funded by Florida State University (2001) and a Fulbright Scholar Award (2002). In 2002 research was also facilitated by a teaching opportunity at the Facultad Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) of Ecuador. I am grateful to all these organizations for their support. In total, I have spent approximately thirty months in Ecuador over the last ten years.

I offer the warmest thanks to Frederick Damon. No citation or acknowledgment herein can do justice to Freds many intellectual gifts that have become part of my own thinking. I acknowledge my debt to the late Chris Crocker, whose vital soul has become something of this work. I thank George Mentore, who brought his entire family to visit my field site in 1996, a moment in time when we finally came to understand each other. I sincerely and most warmly thank the series editor, Norman Whitten, for pushing me to integrate more of my own experiences into the text. Norm was not simply an editor. He was both critical and supportive at the necessary moments and has done much to make this book stronger. I thank him for such generous and astute mentoring throughout the process.

I thank Fernando Santos-Granero, Jean-Guy Goulet, and Thomas Abercrombie for comments on the final chapter they made during the 2003 American Anthropological Association meetings. I also thank Chris Gregory for encouragement. I thank warmly the anonymous reviewers, whose critical insights have improved various aspects of the argument in no uncertain way.

There have been numerous others who must be thanked along the way: Renault Neubauer, Luz Mara de la Torre, Frank Salomon, Carmen Chuqun, and others who helped me to learn Quichua. I would especially like to thank Professor Fernando Garca of FLACSO and the director of the Fulbright program in Ecuador, Susana Cabeza de Vaca. I also thank my two dear friends, Simon Bickler and Syed Ali, who spent a lot of time reading parts or entire chapters of this book. Others who have helped along the way are Carissa Neff, Cheryl Ward, Bill Parkinson, Brian Selmeski, Mark Becker, Tod Swanson, and Alexander King.

I also thank the many Napo Runa people who have contributed to this project and have helped me to understand something of their world. I would like to thank my parents, Don and Linda Uzendoski, and my two sisters, Kerry and Kathy, for much support and encouragement. Lastly, I especially thank my wife and my family in Ecuador, all of whom have contributed greatly to this cause. To the many people I have not mentioned I offer my apologies. While I have received much help along the way, I accept full and complete responsibilities for any errors or shortcomings.

Interpretations of Culture in the New Millennium

Interpretations of Culture in the New Millennium This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.