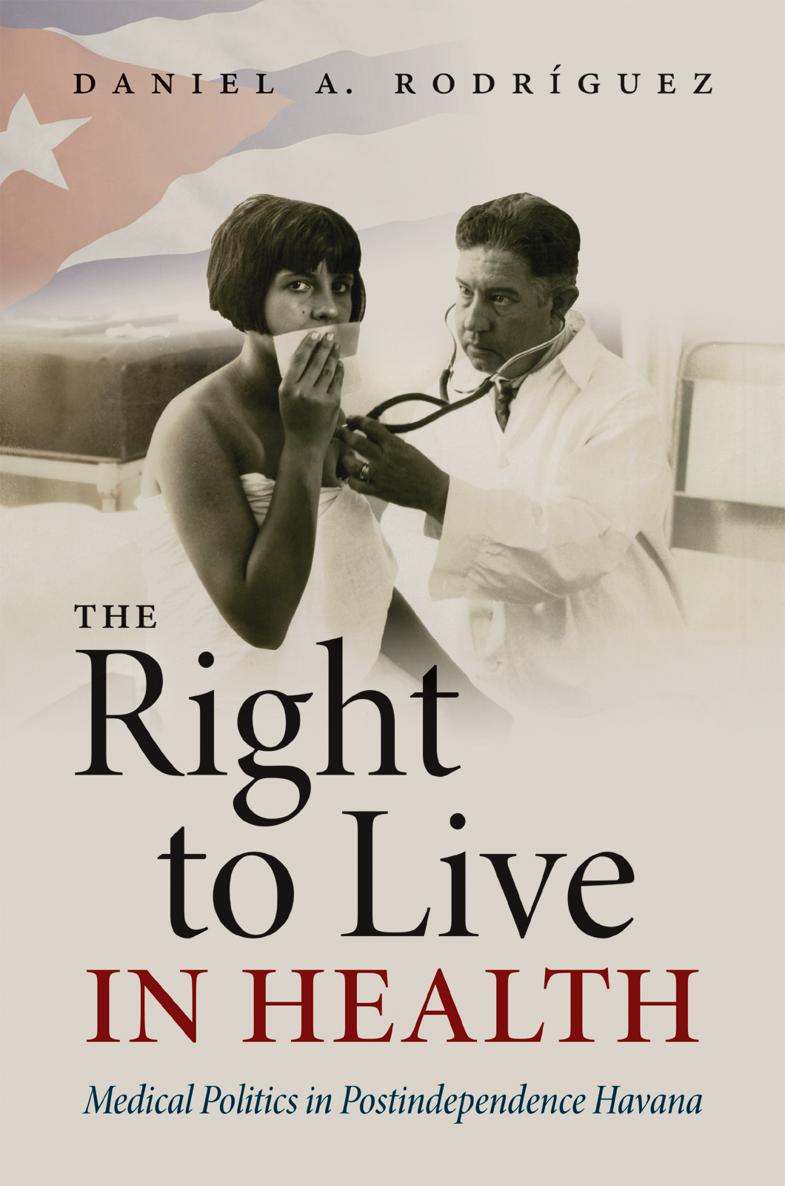

THE RIGHT TO LIVE IN HEALTH

ENVISIONING CUBA

Louis A. Prez Jr., editor

Envisioning Cuba publishes outstanding, innovative works in Cuban studies, drawn from diverse subjects and disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, from the colonial period through the postCold War era. Featuring innovative scholarship engaged with theoretical approaches and interpretive frameworks informed by social, cultural, and intellectual perspectives, the series highlights the exploration of historical and cultural circumstances and conditions related to the development of Cuban self-definition and national identity.

THE RIGHT TO LIVE IN HEALTH

Medical Politics in Postindependence Havana

DANIEL A. RODRGUEZ

The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill

2020 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed and set in Quadraat with Hypatia Sans by Rebecca Evans

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

A version of chapter 4 originally appeared as Daniel A. Rodrguez, The Dangers That Surround the Child: Race, Gender, and Infant Mortality in Post-Independence Havana, Cuban Studies/Estudios Cubanos 45 (2017): 297318. Republished with permission.

A version of chapter 6 originally appeared as Daniel A. Rodrguez, To Fight These Powerful Trusts and Free the Medical Profession: Medicine, Class-Formation, and Revolution in Cuba, 19251935, Hispanic American Historical Review 95, no. 4 (November 2015): 595629. Republished by permission of the copyright holder, Duke University Press.

Cover illustrations: photograph of doctor and patient by Julio Trigo, ca. 1920s1930s (Fototeca, Caja 133, Sobre 117, registro. 4330, Archivo Nacional de Cuba); background, Grunge Flag of Cuba ( Fredex8, iStock).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rodrguez, Daniel A., 1976 author.

Title: The right to live in health : medical politics in postindependence Havana / Daniel A. Rodrguez.

Other titles: Envisioning Cuba.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2020. | Series: Envisioning Cuba | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020004161 | ISBN 9781469659725 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469659732 (paperback ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469659749 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cuba. Secretara de Sanidad y Beneficencia History. | Public health Cuba History 20th century. | Medical policy Cuba 20th century. | Right to health Cuba History 20th century.

Classification: LCC RA395.C9 R63 2020 | DDC 362.1097291 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020004161

FOR SUSAN AND LOURDES

You make it worth it

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IT IS A TRUISM (that is nevertheless too often ignored outside Acknowledgment sections) that all academic work is a collective exercise, all books the product of countless influences and a lifetime of intellectual and personal debts. But it is without a doubt true.

The process of researching and writing this book coincided with a series of political and personal events that have profoundly shaped the writing process. Politically, the United States has been embroiled in over a decade of debate over the proper role of the government in ensuring that its population have access to affordable and quality health care. These debates, which often revolved around issues of the suitability of the capitalist market to meet the health needs of all, and the responsibility of the government in ensuring access, have informed the prism through which I have come to understand the health care debates of early-twentieth-century Cubans. Historical context, of course, matters, and the political culture of the early-twentieth-century United States is profoundly different from that of turn-of-the century Cuba; but I believe that by reflecting on the process through which Cubans came to take up health as a fundamental right rather than a privilege is indeed illuminating for those of us living today.

On a more personal note, as I was writing an early draft of this book, my wife, Susan almost seven months pregnant with our first daughter became acutely ill with preeclampsia and H.E.L.L.P. Syndrome. For the first time, I had to confront the real possibility that both my partner and my child could die. Thankfully, the doctors and nurses at Baystate Medical Center provided my family with the best care one could hope for. My wife made it through, and although our daughter, Lourdes, was born two months premature weighing less than three pounds and fitting in the palm of our hands she is now a thriving and creative first-grader. While these experiences profoundly affected me and my family, they also shaped this book. On an immediate level, they compelled me to research and write a chapter on infant mortality and child health. But they also brought me into deeper consideration of the possible meanings of illness and early death for the men and women who experienced these as a fact of life in Havana, in that period of history when a medical revolution was transforming our understanding of disease, but decades before antibiotics and new medical therapies would transform the ability of physicians to cure common illnesses. This book and my life have been informed by a new appreciation for the precariousness of health and the intertwining of family, medical, and community support that maintains us.

My research would not have been possible without the sponsorship of Cuban research institutions and the generous financial support of U.S. foundations. For sponsoring my research on the island and helping connect me to the vibrant research community there, I am indebted to the Instituto Cubano de Investigacin Cultural Juan Marinello (and especially the ever-capable Henry Heredia), the Instituto de Historia de Cuba, Casa de las Americas, and the Fundacin Antonio Nez Jimnez de la Naturaleza y el Hombre. At different points, my research was made possible by the Tinker Foundation, the Torch Prize Fellowship, the Susan and George Field Summer Research Fellowship, and the Junior Faculty Development and Humanities Research Funds at Brown University. Invaluable time to write was made possible by the generous support of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, the Mellon Foundation, and the Consortium for Faculty Diversity.

The support and warmth of Cuban archivists, librarians, and academics never ceases to amaze me. I am particularly thankful for the knowledge, patience, and support of the islands archivists and librarians, whose often thankless job is to preserve Cubas cultural patrimony, despite the lack of state funding and the relentless attacks of the environment on archives and libraries full of crumbling paper and slowly deteriorating books. My special thanks go to wonderful staff at the Archivo Nacional de Cuba, especially Julio Lpez Valds, Silvio Santiago Facenda Castillo, Jorge Macle, and Olga Pedierro. This project literally could not have happened without the help of Graciela Guevara Bentez at the Museo Nacional de Historia de las Ciencias Carlos J. Finlay, as well as the staff at the Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba Jos Mart and the Instituto de Literatura y Lingstica Jos Antonio Portuondo Valdor. My research was also pushed along by the wonderful community of open and generous Cuban historians, who gave me invaluable advice over cafecitos or amid piles of documents at the archive. Particular thanks go out to Enrique Beldarran Chaple, Brbara Danzie Len, Victor Fowler, Toms Fernndez Robaina, Reinaldo Funes Monzote, Marial Iglesias Utset, Ricardo Quiza Moreno, Alejandro Fernndez, Pedro M. Pruna, Julio Csar Gonzlez Laureiro, and Maikel Farias Borrego.