Nkrumah and Ghana

Kwame Nkrumah was the man that salted Africa.

Nkrumah and Ghana:

The Dilemma of Post-Colonial Power

Kofi Buenor Hadjor

First published in 1988 by

Kegan Paul International Limited

This edition first published in 2009 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kofi Buenor Hadjor, 1988

Transferred to Digital Printing 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 10: 0-7103-0322-X (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-0322-6 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Contents

Dedication

For the people of Ghana and for Philip Yossifov Hadjor and his mother, Sheshinka Avramova, and for the memory of Dr Emmanuel Hansen who died tragically in Arusha, Tanzania, on Friday, 13 November 1987

Preface and Acknowledgements

This book has been a long time in coming. During the days following Kwame Nkrumahs death in 1972, the idea of writing this book first took form. While thinking about what form the book ought to take, I remembered his advice to us in Conakry learn that you can carry on the fight. Back in 1972, I still had a lot of learning to do. With hindsight, it is as well that this project was postponed.

During the past fifteen years, Africa has gone through a major trauma. The events of these years help throw light on the Nkrumah experiment, and underline its continued relevance for Ghana and for Africa. The test of time has proved in Nkrumahs favour. It has provided the author with material evidence of the continuity of the issues which Nkrumah sought to address. The recent revival of interest in Nkrumah throughout Africa, and Ghana in particular, confirms that this book was not written in a vacuum. Ghana and Africa must still do a lot of learning and struggling. We hope this work will convince our readers that it is so, and take on board the best of the tradition that we inherited from Nkrumah. And in line with Nkrumahs emphasis on making knowledge accessible to the widest possible audience, we have also written a popular version of this text, particularly aimed at Africas youth.

Many friends and colleagues have given me tremendous support in the writing of this book. Special thanks, however, go to the following:

Patrick Smith, Dede-Esi Amanor and Judy Hirst for researching most of the text,

Pauline Tiffen for the index,

Cary Yageman for inputting the entire manuscript into the computer,

Kabral Blay-Amihere for providing the bibliography,

Sharmini Brookes, Laura and Ruth Brako also deserve my thanks for their various roles,

my thoughts for Kemi and Joy.

Kwame Nkrumah, A Beginners Guide to African Liberation. London and Accra, Third World Communications, 1988.

Introduction

by

John K. Tettegah

Kwame Nkrumah died in April 1972, more than fifteen years ago. For those of us who knew him it appears as if the great tribune is still with us today. His powerful message and analysis of the African condition are confirmed every month, year after year.

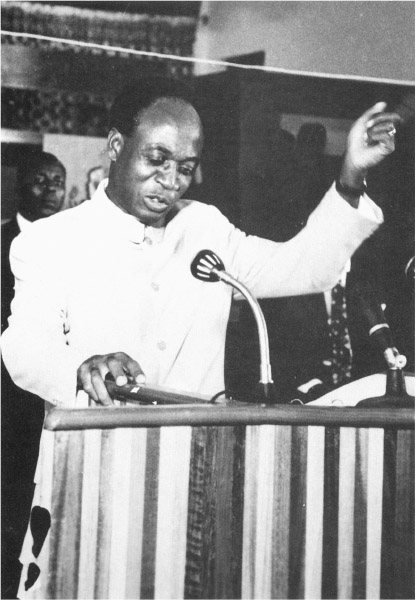

Throughout his life, Nkrumah was in the forefront of the struggle to build a new Africa. His pioneering efforts in the field of anti-colonial resistance, political analysis and philosophy are now recognised throughout the world. He was above all a natural leader of his people. To a considerable extent it was his leadership that was responsible for ensuring that Ghana would become the first African nation to win its political independence in the post-war period. Under Nkrumah Ghana became the centre of the African revolution, setting the pace for the rest of the continent.

Those who opposed change in Africa looked upon Nkrumah as their most bitter enemy. In the Western media he was constantly vilified as a dangerous trouble-maker. On many occasions he was the target of assassination attempts. In the end the CIA organised an attempt to overthrow his government in 1966. The enemies of Africa were determined to destroy him. While they succeeded in forcing him into exile, they failed to discredit the man. Nkrumah would not be silenced. To his last day Nkrumah breathed the fire of African freedom and unity. Africa still has much to learn from Nkrumah. No African nation can feel safe in an international order where foreign adventurers are free to prey on the continent. The world economic order is a hostile force which continues to plunder Africas resources. Unequal terms of trade and exorbitant interest rates ensure that every year a significant portion of Africas wealth is lost to the continent. A network of foreign military forces American, British, French spread all over the continent stand prepared to back up those economic interests. The apartheid regime of Pretoria is a permanent threat too. The threat of war and foreign intervention hangs over much of Africa indicating that the struggle against colonialism has not yet been won.

All this Nkrumah anticipates in his writings. Nkrumah knew that even political independence was only a temporary gain. The former colonial powers were not prepared to abandon their stake in Africa. By hook or crook they have sought to keep Africa under their control. Nkrumah would not have been surprised at the invasion of Angola and Mozambique or the air raid on Libya. He argued convincingly that if Africa could not be united it would be destroyed.

And yet Nkrumah was essentially an optimist. He had profound faith in the energy and dynamism of Africa. He knew that history is on Africas side. His main concern was to ensure that his people were ready to assume the responsibility thrown on them by history. For the new generation of Africans Nkrumah represents the essential starting-point. Nkrumah and Ghana reconstructs Nkrumahs life so that the reader can share in his rich experience.

It was only a question of time before Hadjors authoritative analysis of Kwame Nkrumahs life would appear. During our exile in Conakry and Cairo, Hadjor and I were both concerned that the lessons of Nkrumahs experience should not be lost to the future generations of Ghana in particular and the rest of Africa in general. It was at this point in time that the ideas contained in the work began to take shape.