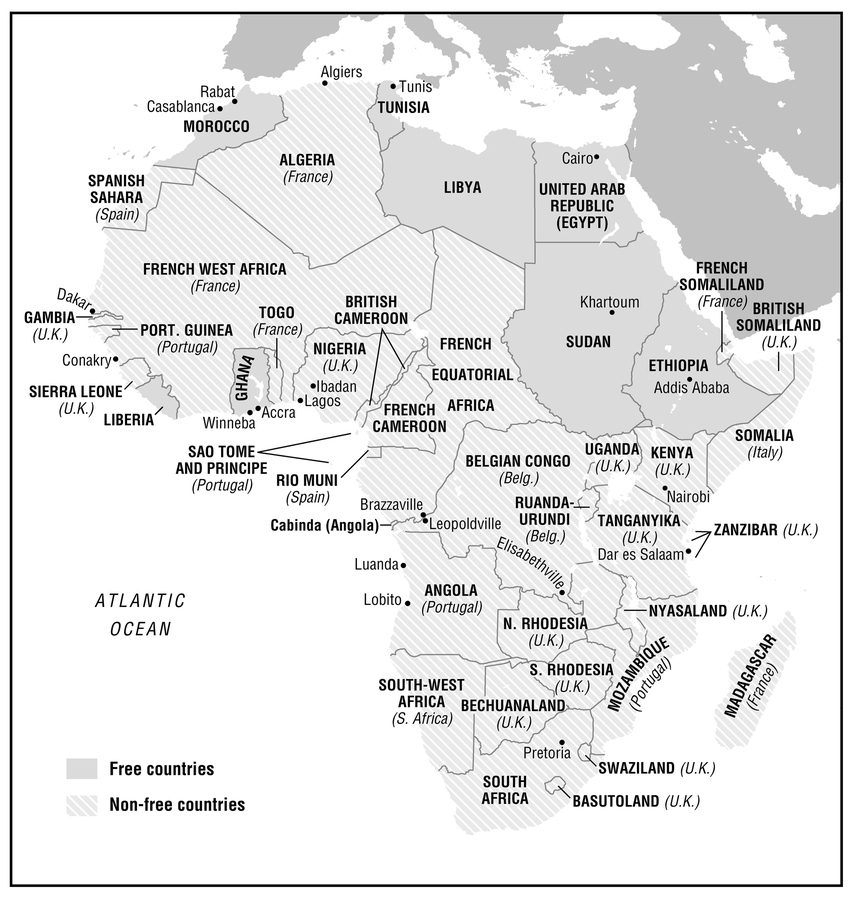

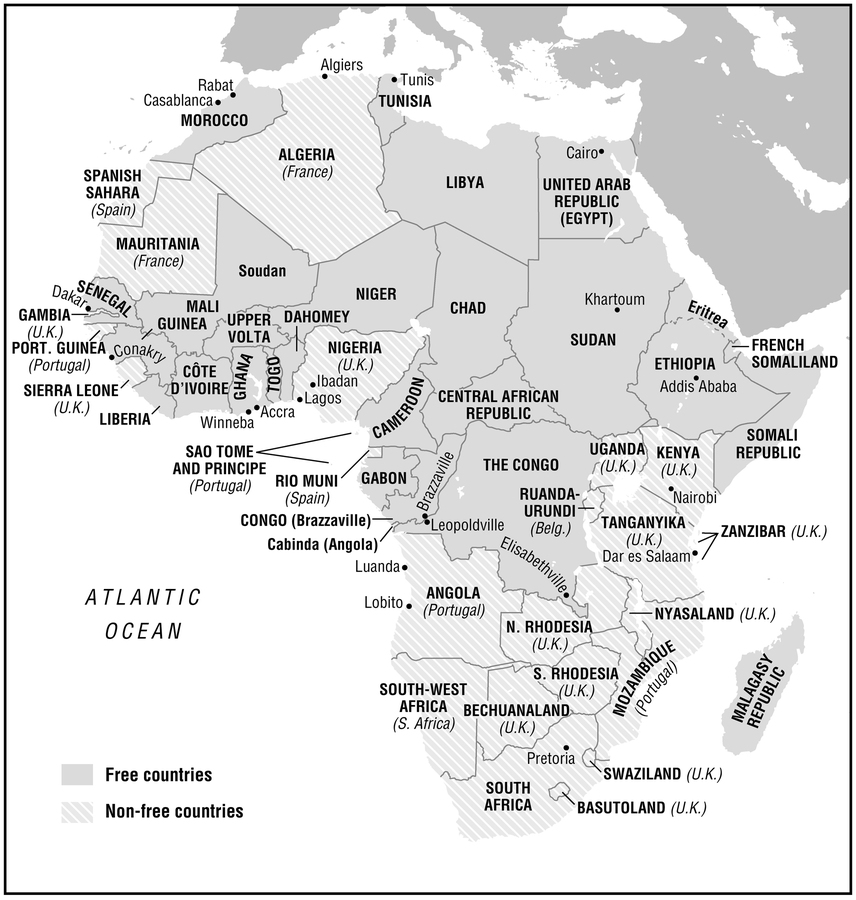

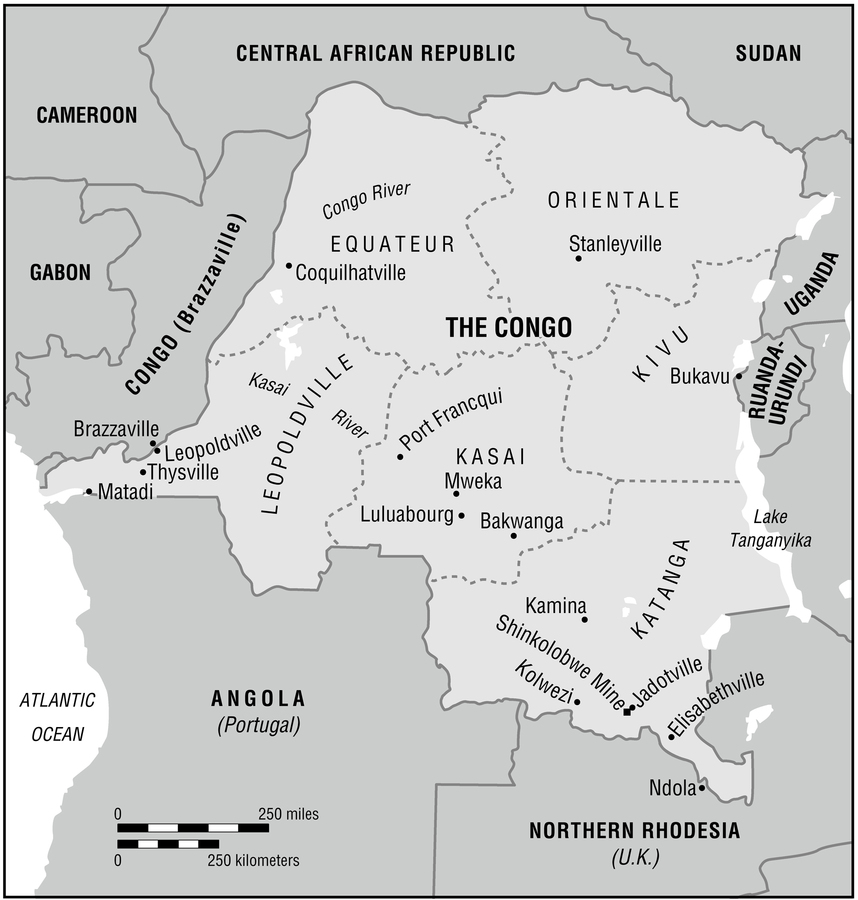

The Congo at independence from Belgium, 30 June 1960.

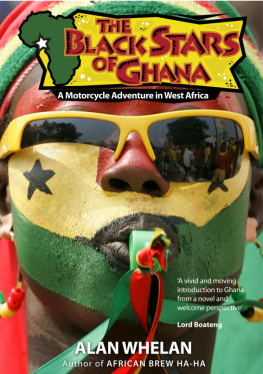

T HE HOURS OF THE DAY had been hot and charged with thunder. As darkness fell, the humid atmosphere in Accra felt explosive. Even so, the crowds had swelled along the coast, and the streets were heaving. Suddenly, the newly built Arch of Independence was floodlit against the blackness of the sea. The monument was inscribed with a short but powerful message: Freedom and Justice. A.D. 1957. It stood on the spot where three unarmed men had been shot dead nine years earlier, when a British police officer had ordered his men to fire at a peaceful deputation from the African Ex-Servicemens Union. Now, it marked the start of a new era. Fireworks soared into the sky above the arch.

At the stroke of midnight, bells pealed loudly. Then the Union Jack flying above Parliament House was hauled down, and the new flag of Ghana was solemnly raised up, for the first time. As it reached the top of the pole, it fluttered slowly in the night airred, gold and green, with the black lodestar of Africa at its centre. Cries of happiness rang out, and people danced and sang in jubilation. Over and over, people cheered and shouted out at the top of their voices: Freedom! Ghana! Nkrumah!

Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah was carried shoulder high to a dais in the Old Polo Ground, close to the roaring surf of the Atlantic Ocean. Under a flood of lights, Nkrumahs open face and large, steady eyes looked out at the thousands in front of him. Forty-eight years old, he had spent much of his life working for this moment, as had so many others. He wore a cotton smock from the north of Ghana and a Gandhi-type prison cap, marked with the initials PG, standing for prison graduate. It was a badge of honour worn with pride by many Ghanaians, in remembrance of their unjust imprisonment by the British.

The noise of the crowd was deafening. Then Dr Nkrumah held out his arm to command attention, with solemn authority. He called for a minutes silence to give thanks to God. Then he asked everyone to remove their hats, as the police band played the new national anthem, Ghana Arise! Tears streamed down his face, and many in the crowds were sobbing. Unmistakably, on 6 March 1957, the people of Ghana were free. The British colony of the Gold Coast was no more, and Ghana had become the first Black-majority country to obtain independence from colonialism, blazing a trail for the African continent.

At long last, proclaimed Nkrumah, the battle has ended and Ghana, our beloved country, is free for ever. Then, choked with emotion, he fell silent. It was an unforgettable moment for Cameron Duodu, a young cub reporter. Just sixteen wordsno more, he wrote later. But no-one who heard them would ever be able to forget them. The cheers that greeted those sixteen words were, of course, out of this world. The iconography of Ghanas independence ceremony followed the pattern set by India on 15 August 1947, ten years earlier. Then, too, the Union Jack had been lowered and replaced by the new Indian flag at midnight.

But Ghana was not copying India for dramatic effect. It was following Indias clear commitment to international nonalignment, led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. This commitment had been a major theme of the Bandung Conference of African-Asian states in 1955, in which the Gold Coast participated. There, led by Nehru, Indonesias Sukarno, and Egypts Gamal Abdel Nasser, twenty-nine emergent nations across Africa and Asia had sought to lay the foundations of a nonaligned third force, to resist the pressures from the West and from the East in the context of the Cold War.

Not only in Ghanas capital Accra, but also in Kumasi, Tamale, Sekondi-Takoradi, and Cape Coast, similar ceremonies took place, where the Union Jack was replaced with the new flag. Families in the churches and the mosques sent prayers to God. In the nightclubs, exuberant throngs danced to the Highlifea popular fusion of Ghanaian musical traditions with Western instruments.

The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr and his wife, Coretta Scott King, who had come from America to celebrate Ghanas freedom, were a part of the crowd in Accra. These young civil rights campaignersDr King was just twenty-eight years oldwere profoundly moved. Before I knew it, declared Dr King in a sermon the following month to his congregation in Montgomery, Alabama, I started weeping. I was crying for joy. And I knew about all of the struggles, and all of the pain, and all of the agony that these people had gone through for this moment.