2018 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gupta-Carlson, Himanee, author.

Title: Muncie, India(na) : Middletown and Asian America / Himanee Gupta-Carlson.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2018. | Series: The Asian American experience | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017031763 | ISBN 9780252041822 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252083440 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: South Asian AmericansIndianaMuncie. | ImmigrantsIndianaMuncie. | Gupta-Carlson, Himanee. | Muncie (Ind.)Ethnic relations. | Muncie (Ind.)Social conditions. | Muncie (Ind.)Biography. | Lynd, Robert Staughton, 18921970. Middletown.

Classification: LCC F534.M9 G87 2018 | DDC 305.8009772/65-dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017031763

Acknowledgments

T his book is about Muncie, Indiana, the small city famed for its typicality. I grew up in Muncie in the late 1960s and 1970s, and left in 1981 with no intention of ever returning. However, when I decided in 2000 that I would make the city the site of my doctoral research, my relationship with Muncie forever changed. Over the many years that it took to write, revise, and re-revise this book, I made dozens of trips to Muncie while residing first in Honolulu, then in Seattle, and finally in Saratoga County, New York. I benefited from the insights, commentary, and support of numerous people along the way. This reminds me that even when a written work bears the name of a single author, the product is the result of many.

In Honolulu, I was guided as a doctoral candidate by Michael J. Shapiro, Kathy E. Ferguson, Sankaran Krishna, Nevzat Soguk, and David Stannard. I also gained valuable insights in these years from professors Geoffrey White, S. Charusheela, Monisha Das Gupta, and Jagdish and Miriam Sharma, and support from many University of Hawaii colleagues and friends, including Grace Alvaro Caligtan, Melisa Casumbal-Salazar, Maigee Chang, Jenny Garmendia, Kathleen Hurtubise, Diane Letoto, Jackie Palmer-Lasky, and Melly Wilson. I owe especial thanks to Eundak Kwon and Bianca Isaki for their close reads, edits, and comments on the initial project.

In Seattle, creative writers of many genres helped me re-envision the project as a book, including Wendy Call, Ferdinand DeLeon, Waverly Fitzgerald, and Edward Skoog. I am grateful to the Richard Hugo House for creating a space for me to connect with so many writers and to the Artist Trust of Seattle for accepting me into its inaugural Literary EDGE program for writers.

In Saratoga, my SUNY Empire State colleague and friend Menoukha Case read and commented on nearly every chapter in the book, probably twice. I owe her a special debt. I also thank Michele Forte for talking me through several rearticulations of various chapters as I prepared the manuscript for submission. Numerous faculty professional development grants, an individual development award from the United University Professions, and acceptance into two college-sponsored writers retreats also helped me not only bring the book to completion but also share the work in progress at academic conferences.

I was fortunate to have been accepted into the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning in Theology and Religions workshop for Pre-Tenure Asian and Asian American Teaching Faculty in 201112. There, I met David Yoo, who not only offered splendid advice on publishing within Asian American studies but also introduced me to Vijay Shah, then an editor with the University of Illinois Press. Shah enthusiastically supported my proposal and put the manuscript under contract. Dawn Durante continued Shahs work, and I thank her for her kindness and her patience. I also thank Julie Gay for her close copyedit of the final manuscript. Other scholars who played a crucial role in helping me bring the book to completion are Tamara Ho, Jigna Desai, and the anonymous reviewers who offered tough yet supportive comments.

The fifty-one individuals I interviewed for this project gave me time, stories, food for thought, and memories that I carried with me throughout the entire process of writing this book. I cannot thank this group enough, and I wish I could name them individually without betraying the confidentiality instilled by academic protocols. I can, however, name the five people who traveled with me almost constantly on this journey: my parents, Naim and Shailla Gupta; my sisters, Nisha Gupta and Anju Gupta-Lavey; and my husband, Jim Gupta-Carlson. Their stories are the core of the book, and their love and support have been vital to making it a reality.

Finally, I wish to acknowledge the support I received from the Center for Middletown Studies at Ball State University and the many people in Muncie itself for providing me with time, references, and memories to tap. Without Muncie, there would not be this book. Muncie has become a city that I am now happy to call my hometown.

Muncie, India(na)

Introduction

Wind tugging at my sleeve

feet sinking into the sand

I stand at the edge where earth touches ocean

where the two overlap

a gentle coming together

at other times and places a violent clash.

Gloria Anzalda, Borderlands/La Frontera:

The New Mestiza, 1999

Stillwater, Minnesota

October 7, 2005

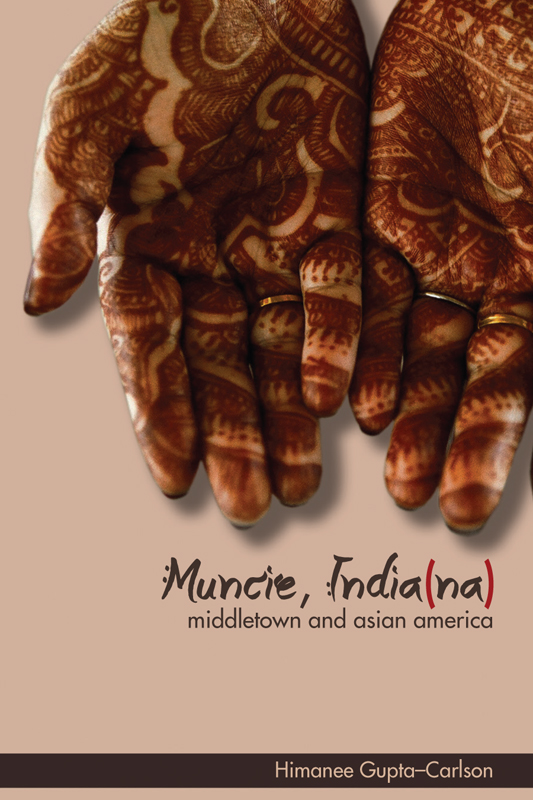

I heard a quiet, rhythmic drum tapping as my fianc Jim and I approached a Holiday Inn party room on the night before our wedding. My parents had rented the room for the Indian premarital party known as a sangeet, and as we walked in, I saw a familiar sight: large white sheets spread over a carpet on which women in saris and salwar kameez were seated comfortably cross-legged. A longtime family friend was drumming on a tabla. She had emigrated three decades earlier with her husband from Ahmedabad, India, to Muncie, Indiana, where our families met. With her were my mother, two aunties, and several South Asians from Muncie who had become an informal part of our family in the four-plus decades that we had all been collectively a part of the United States. Friends and family mingling like this had created a diaspora kinship pattern of lineage and love that prompted so many of them to come from wherever they lived in the United States to celebrate my marriage to Jim, the grandson of Swedish and German immigrants who had settled in Minnesota in the early twentieth century.

Jim gripped my hand tightly. A celebration composed of elements of my Hindu Indian heritage was new to him. He told me with his eyes and with his fingers clenched around mine that he felt out of place. His nervous grip added to my worries about the tensions I sensed in the room. I looked around and saw Jims parents, sisters, brothers-in-law, nieces, and nephews on chairs at the edge of the sheet-covered spaces of carpet. I imagined that they too were uncomfortable. I translated the discomfort into disapproval, and this had the effect of filling me with shame over our Indian ways.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.