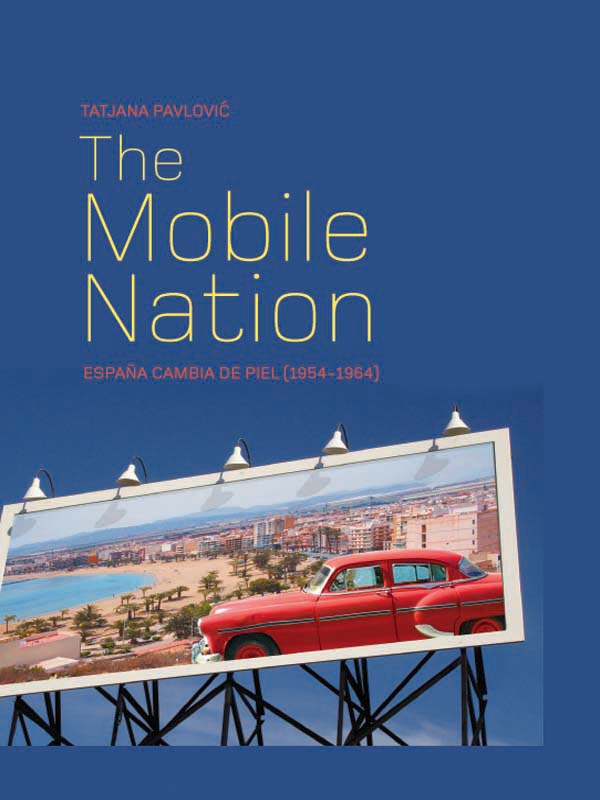

The Mobile Nation:

Espaa cambia de piel (19541964)

The Mobile Nation:

Espaa cambia de piel (19541964)

by Tatjana Pavlovi

First published in the UK in 2011 by Intellect,

The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK

First published in the USA in 2011 by Intellect, The University of Chicago Press,

1427 E. 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Copyright 2011 Intellect Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover design: Holly Rose

Typesetting: John Teehan

ISBN 9781841503240

Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta.

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several individuals and institutions have contributed to the making of The Mobile Nation: Espaa cambia de piel (19541964). Many ideas incorporated into this book have resulted directly or indirectly from discussions with friends over the several past years. It could not have been written without intense conversations, theoretical debates and the friendship of Anthony Leo Geist, Isolina Ballesteros, John Charles, Marline Otte, Ari Zighelboim, Laura Bass and Henry Sullivan. Henry gets my extra-special thanks for helping to smooth out some rough spots in the manuscript, far-ranging insights and careful judgement. He read the entire manuscript and thoughtfully engaged its arguments. My sense of his personal and intellectual support goes well beyond the pages of this book. I am also grateful to Camillo Penna and Suna Ertugrul for their friendship and for bringing my attention to certain key theoretical texts. Their own relationship to theory and writing has been very important to me during the composition of this book. Above all, I pay tribute to my mother Biljana Pavlovi, who originally instilled in me the love of books and reading.

At Tulane University, I am fortunate to be surrounded by talented and generous colleagues who are also true friends. My deepest thanks go to them and to our Chair Marilyn Miller for her consistent support. I also wish to thank my students at Tulane University in a wide range of courses on Spanish cinema, film history and film theory who have listened to early versions of the manuscript and raised many excellent questions. Several scholars working on contemporary Spanish culture have read earlier versions of various chapters and given me valuable critical feedback. Special thanks also go to my colleagues in Spanish Film Studies from the United States, Spain and the United Kingdom who have been remarkably generous in sharing their work and expertise: Marvin DLugo, Katy Vernon, Eva Woods, Susan Martin-Mrquez, Steven Marsh, and Josetxo Cerdn. Since my student days I have always been inspired by Jo Labanyi and Paul Julian Smith, two outstanding scholars of Spanish literature, film and visual culture. Their work continues to be essential to my own understanding of Spain and its cinema.

This book could not have been written without the help of various institutions in Spain and the United States. The Deans Office of the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Tulane University provided me a Research Grant in the summers of 2007 and 2009 and a Junior Research Leave during the 20032004 academic year. That same office was also generous in aiding Intellect Publishing of Bristol, United Kingdom, with publication costs. Funding from The Program for Cultural Cooperation between Spains Ministry of Culture and United States Universities allowed me to spend two summers (2005 and 2006) viewing many films discussed in the book. I am also indebted to Margarita Lobo and other personnel of the Filmoteca Espaola who have been tremendously helpful in providing me access to the Filmotecas collection. At Intellect Publishing, I would like to thank the Associate Publisher, May Yao, for her efficiency, patience and commitment to the project. I am also indebted to Integra Software Services for their diligent copyediting and to the typesetter, John Teehan. In addition, I also thank Holly Rose for the design of the cover, which uncannily captures the spirit of the book and period studied.

Sections from the Introduction appeared in an earlier version as Espaa cambia de piel: The Mobile Nation (19541964), Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, Vol. 5, Issue 2, July 2004: (213226). A condensed portion of Chapter 2 was published as Television (Hi)stories: Un escaparate en cada hogar, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, Vol. 8, Issue 1, March 2007: (521). I gratefully acknowledge the publishers of these articles for permission to reproduce parts of them in this book.

This book is dedicated to my two great loves: my life-partner Rachel and our son Constantin. Rachels keen critical acumen and understanding of the project shaped the way I look at Spanish cinema. Above all, she was my companion in the pleasures of filmgoing and film-viewing. Our shared love of cinema and literature was a main impetus in writing The Mobile Nation. But while this project is now over, she continues to inspire me into an unlimited future.

I NTRODUCTION

The Mobile Nation: Espaa cambia depiel (19541964) focuses on a period of transition in the history of Spanish culture that has not received sufficient critical attention.1 Several forces converged in the early 1950s to put Spain on a path of integration with the more developed countries of Europe. Autarkic Spain abandoned its outdated and sluggish economic model developed mostly as a response to Spains international isolation following the Spanish Civil War.2 It gradually curbed the state interventionism that had been an integral part of autarkic economic principles. Autarky, a type of economic nationalism, had formed part of Francos stock rhetoric by which the post-war ostracism of Spain was modified, even eulogized as a self-sufficient, autonomous cultural polity sustained, among other strategies, by an insistence on the superiority of Spains blessd backwardness (bendito atraso).3 With this easing of autarkist principles, the government needed to reframe its political tactics, visible in a revision of nationalist rhetoric that now defined progress as a technocratic mutation of the prevailing ideology. The regimes self-justification ceased to be metaphysical and became more frankly material. The insistence on an Eternal Spain with its religious essence and God-chosen destiny was no longer desirable or optimal and was replaced by the language of efficiency, rational thinking and a belief in high living standards. The triumphalist, bellicose discourse of the postwar period now centred on a rhetoric of prosperity and an ever-broadening horizon of expectations. Francos regime ceased to be providential and became technocratic. Spaniards would no longerbe preparing for the heavenly paradise, but enjoying an earthly one. A discourse sustained by the old-fashioned values salvaged from the Civil War now morphed and became compatible with the siren call of hedonism. A society of sacrifice become a society of leisure, much more in line with emergent global consumerism.