Copyright 1993, 1994 by The Regents of the University of California

Originally published in 1993 by the Asian American Studies Center, UCLA, as volume 19, no. 2 of Amerasia Journal.

First University of Washington Press edition, revised and with a new preface, 1994

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

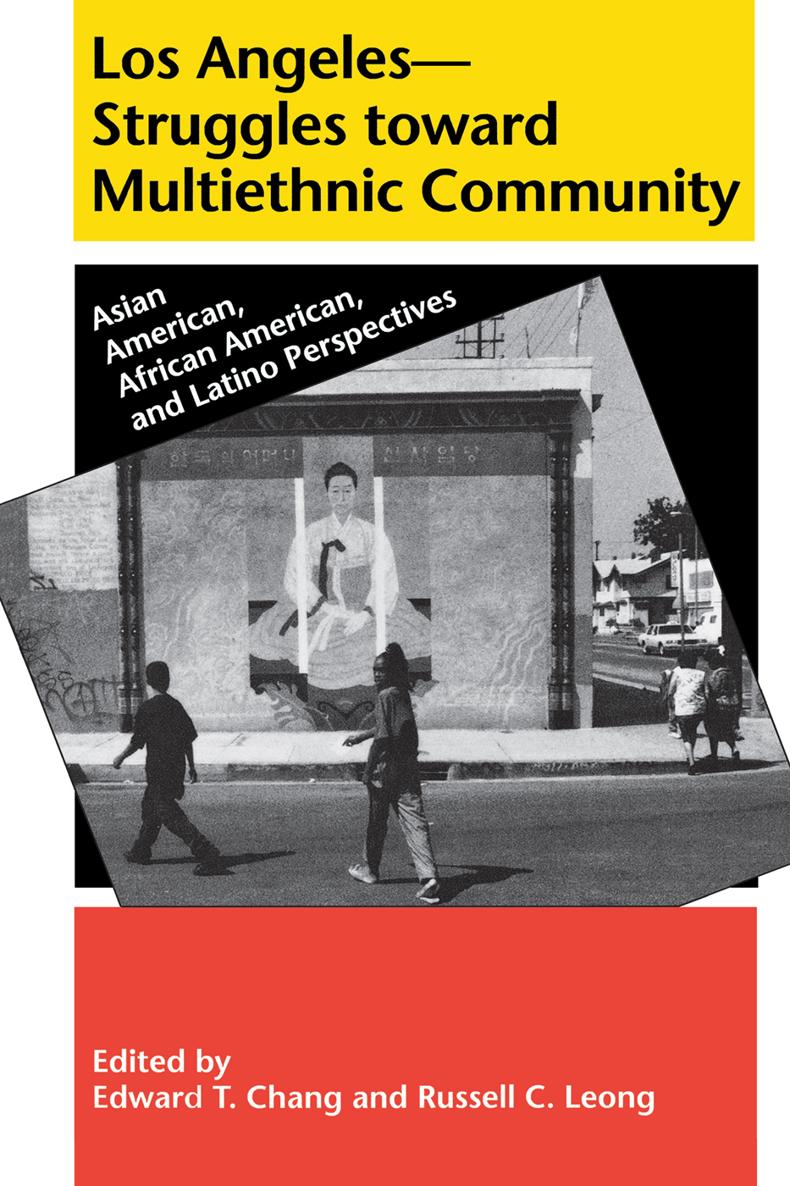

Los Angelesstruggles toward multiethnic community : Asian American, African American, and Latino perspectives / edited by Edward T. Chang and Russell C. Leong. 1st University of Washington Press ed.

p. cm.

Originally published in 1993 by the Asian American Studies Center, UCLA, as volume 19, no. 2 of Amerasia journalT.p. verso.

ISBN 0-295-97375-7 (alk. paper)

1. Los Angeles (Calif.)Ethnic relations. I. Chang, Edward T. II. Leong, Russell C.

F869.L89A24 1994 | 94-32758 |

305.800979493dc20 | CIP |

Cover photograph by Eugene Ahn: At Western and 15th in Los Angeles, schoolchildren pass the mural of Madame Shin-sa-im-dang (1504-51), a poet and painter of the Yi Dynasty who in Korea today symbolizes the talented, beautiful, accomplished woman and virtuous wife and mother.

Preface

The Making of Los AngelesStruggles toward Multiethnic Community

RUSSELL C. LEONG

In the City of Angels, the fire and smoke had not yet begun. Three years prior to the L.A. uprising, Edward Chang and I were grabbing a quick meal in a fast food restaurant in the heart of Koreatown in Los Angeles. The family-run Korean eatery was located in a brand-new indoor mall near Western and Olympic avenues. Inside the mall we could see Koreans, butwith the exception of one strolling coupleAfrican Americans were noticeably absent. If one looked carefully, Latino men were present, usually lifting, cutting, or bagging in the supermarket or tucked behind counters in the restaurant kitchens. Partly because of their height and dark hair, which are similar in Asians, the Latinos did not stand out. Yet, we could not take their blending for granted; indeed, growing numbers of Asians and Latinos especially in Los Angeles were changing the complexion of race relations, which could no longer be defined as Black and White.

As we ate our noodles and kim chee, Edward and I talked about the 1990 Red Apple Grocery boycott in Brooklyn, New York, and about the economic conflicts and racial tensions that were bound to escalate in South Central Los Angeles. Previously all-Black neighborhoods were now predominately Latino; Korean-owned stores had replaced Jewish-owned ones in the same communities. Edward, a Korean American sociologist and civil rights activist, and myself, a Chinese American poet and editor, from our different vantage points, could see the racial clock ticking. The broad face of the clock was white, but the moving hands, numbers, and hours were black. But where did the Asians and Latinos fit in this timely scheme of things?

We concluded that one key to building multiethnic community was through educationteaching our own communities about one another: Asian, Latino, African American. We knew we had a vehicle for education in the Amerasia Journal, the national interdisciplinary publication of UCLAs Asian American Studies Center, with its editorial board and dedicated staff. We began to contact individuals who we knew were committed to analyzing race and ethnic relations in this city and in the nation and who were not afraid to tackle their controversial and contradictory aspects. But the Rodney King case, the Latasha Harlins killing, and the L.A. uprising occurred as we were putting together a special issue of the journal, and the articles had to be constantly revised during the editing process. Ella Stewart completed her study of communication patterns between Korean and African Americans before the uprising, for example, and then spent many months revising it to reflect conditions after the crisis.

The present volume, based upon this 1993 special issue of Amerasia Journal, focuses on race and ethnic relations in Los Angeles as they have emerged from the uprising and as they exist in the broader national picture. The uprising revealed that radical approaches are needed to address structured social, economic, and political inequality and pressing issues of race and representation in the literature, media, and culture.

Our goal for this volume was to gather a variety of academic and journalistic perspectives and commentary, as well as creative and literary approaches to building multiethnic community. Scholarly essays include Jewish and Korean Merchants in African American Neighborhoods, by Edward Chang; Communication between African Americans and Korean Americans: Before and After the Los Angeles Riots, by Ella Stewart; Asian Americans and Latinos in San Gabriel Valley, California, by Leland Saito; The South Central Los Angeles Eruption: A Latino Perspective, by Armando Navarro; Race, Class, Conflict and Empowerment: On Ice Cubes Black Korea, by Jeff Chang, and Which Side Are You On? by Arvli Ward. Commentaries by Asian and African American writers feature Larry Aubry, Angela E. Oh, Sharon Park, Amy Uyematsu, Erich Nakano, Walter Lew, and Miriam Ching Louie.

A special feature of this collection is a section entitled Seoul to Soul that showcases literary writings by African and Asian American writers and artists from Los Angeles, including Mari Sunaida, Ko Won, Wanda Coleman, Mellonee Houston, Sae Lee, Nat Jones, Arjuna, Chungmi Kim, and Lynn Manning. Seoul to Soul was based on the first reading by Black and Korean writers held in Los Angeles, which took place before the L.A. uprising.

Los Angeles has emerged as a focal point for social scientists as they develop new ideas about race relations, questioning previous theories and notions of the American melting pot and of a pluralistic society. We hope that Los AngelesStruggles toward Multiethnic Community opens and stimulates the dialogue among groups that previously were speaking in limited ways with one another, and that it will encourage us to examine our own communities, wherever we may live in the United States, in fresh, critical, and constructive ways.