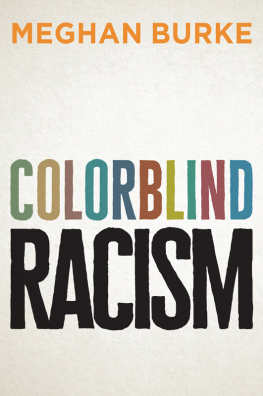

The Cultural Politics of Colorblind TV Casting

This book fills a significant gap in the critical conversation on race in media by extending interrogations of racial colorblindness in American television to the industrial practices that shape what we see on screen. Specifically, it frames the practice of colorblind casting as a potent lens for examining the interdependence of 21st-century post-racial politics and popular culture. Applying a production as culture approach to a series of casting case studies from American primetime dramatic television, including ABCs Greys Anatomy and The CWs The Vampire Diaries, Kristen Warner complicates our understanding of the cultural processes that inform casting and expounds on the aesthetic and pragmatic industrial viewpoints that perpetuate limiting or downright exclusionary hiring norms. She also examines the material effects of actors of color who knowingly participate in this system and justify their limited roles as a consequence of employment, and finally speculates on what alternatives, if any, are available to correct these practices. Warners insights are a valuable addition to scholarship in media-industry studies, critical race theory, ethnic studies, and audience reception, and will also appeal to those with a general interest in race in popular culture.

Kristen J. Warner is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Telecommunication and Film at The University of Alabama. Her research interests are centered at the juxtaposition of televisual racial representation and its place within the media industries, particularly within the practice of casting. Warners work can be found in publications such as Television and New Media and Camera Obscura.

Routledge Transformations in Race and Media

Series Editors: Robin R. Means Coleman University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Charlton D. McIlwain New York University

1 Interpreting Tyler Perry

Perspectives on Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality

Edited by Jamel Santa Cruze Bell and Ronald L. Jackson II

2 Black Celebrity, Racial Politics, and the Press

Framing Dissent

Sarah J. Jackson

3 The Cultural Politics of Colorblind TV Casting

Kristen J. Warner

First published 2015

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2015 Taylor & Francis

The right of Kristen J. Warner to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Warner, Kristen J., 1981

The cultural politics of colorblind tv casting / by Kristen J. Warner.

pages cm.(Routledge transformations in race and media)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Television programsCastingUnited States. 2. African Americans on television. I. Title.

PN1992.8.C36W38 2015

791.450232dc23 2015001394

ISBN: 978-1-138-01830-3 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-77982-9 (ebk)

Typeset in Sabon

by codeMantra

To Linda: Mama, We done it!

Years ago I attended a friends wedding rehearsal dinner, and after noticing that save for the staff I was the only person of color attending the soiree (and understanding that the staff were practically invisible as it was and therefore did not count from the onset), I set out to be myselfjust a smidge more demure. I sat with my party at a very large round table just as another group of young (er) people asked if they could join us. Welcoming the new company, we began to chat, and at some point later in the evening, one of the men confessed that his dream was to become the mayor of a large city. After first discussing the smaller cities that might embrace him as mayor, he told me about the oft-times ridiculous ordinances in small towns. After hearing his story about viewing an official city regulation handbook courtesy of a stika, I was intrigued. First of all, what was a stika? I tried to guess by way of context clues and descriptions and imagined a police officer or a city worker. Giving up the guessing game, my friends and I decided to ask, and the group laughed and told me that it was their alma maters secret society. One of the women at the table laughed and said it was short for swastika.

At that moment I went from deeply engaged and jovial to shocked. But I never said a wordI just looked surprised. At that moment the woman said to me, Oh no, no, no not that kind of swastika, and then after a beat, Dont kill the messenger. In five minutes I went from a supposedly blended individual to a potentially violent Black woman who, after cursing her, might have reached across the table in my jersey-knit Grecian style dress and choked her with one of my many gold bangles or might have stabbed her with my butter knife. Or I might have just called her a racistwhich she was expecting. Her embarrassment matched mine because I perceived that the joint contract the dinner table party had unconsciously agreed to was that of my racial non-recognition, and the minute she uttered swastika the contract became null and void. I became visible as a potential aggressor. It was not my doing or by my choice; rather it felt like an outing or the ripping away of my invisibility cloak. While the whole experience outraged my friends, my powerlessness in that situation was present albeit benign because ultimately I lost nothing, and I walked away mostly unscathedmostly.

This is one of many stories I could tell and represents the personal underpinning of this entire project. On the semesters when I teach the Race and Gender courses, I acknowledge out the gate that I have an agenda that will inform how the class is organized. Indeed, I have an agenda and a mission that can be easily discerned within these pages: an axe to grind against colorblindness as a societys way of literally choosing not to see the world. Individuals who practice this normative social deficiency do not perceive the other until that other is unexpectedly recognized as a threat. Moreover, I believe colorblindness is not only problematic but wrong because it does not remotely aspire to the ideals of fairness. Consider the paradox that I cannot be colorblind because that would mean denying myself and all of the experiences that coincide with this skin I wear. As Patricia J. Williams asserts, the failure to deal with the devastating effects of colorblindness can lead to a self-congratulatory stance of preached universalism:

We are the world! We are the children! was the evocative, full-throated harmony of a few years ago. Yet nowhere has that been invoked more passionately than in the face of tidal waves of dissension, and even as the children learn that we children are not like those, the benighted creatures on the other side of the pale.

Williamss quote is powerful because it speaks to the double consciousness of people of color who, on the one hand, want to belong and desire to believe in the collective we but who, on the other hand, also recognize that the cost of joining is that their difference cannot be acknowledged and, what is more, that even to suggest that difference might be important would transform them into instigators of racial division. The paradox is clear: a message of universal good will renders people of color invisible.