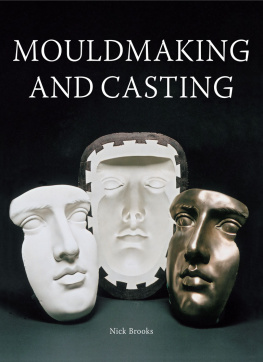

MOULDMAKING

AND CASTING

Nick Brooks

First published in 2005 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

This impression 2010

Nick Brooks 2005

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 730 4

Dedication

To Clementine and Talia, my best work ever.

Acknowledgements

Clementine, Talia and Dan for technical assistance.

Clive and Diana.

Jack Ludlum (www.londonpaparazzi.com) for photographic contributions.

Simon and Anna Cooley for sculpting and modelling clay portrait head in .

Tony Lall-Chopra and Sabine Heitz for mouldmaking and modelling in .

Central Saint Martins' staff for encouragement and support.

Norman Balon for C&H services.

Brendan and Vicki.

Buzzcocks for broken ankle.

Praveera for being there at the beginning.

Alec Tiranti Limited - Sculptors' tools, materials and equipment, established 1895, for supply of all mouldmaking and casting materials used in producing this book.

Disclaimer

Safety is of the utmost importance in every aspect of mouldmaking and casting work. When using tools and/or chemicals, always closely follow the manufacturer's recommended procedures. The author and publisher cannot accept responsibility for any accident or injury caused by following the advice given in this book.

'Leaf'. By Antigoni Pasidi. Silicone rubber, life-size.

PREFACE

I have taught and practised mouldmaking and casting techniques and processes for many years, and have been encouraged to write something on the subject many times. It is not an easy subject to put into the written word - the multiple possibilities and unique requirements of any individual project potentially present as many multiple alternative possibilities. However, there are a number of fundamental techniques that can be taught; these represent a starting point for anyone interested in the subject, and can then be adapted, combined and even potentially 'reinvented' to an individual project (there are few 'rules'!).

When considering this project, I came to the conclusion that the main requirement was for a book that would explain and illustrate the principal techniques and processes. These techniques and processes may be covered elsewhere individually, but are seldom to be found combined in the one book. I have learnt many of the techniques and principles contained here formally but then adapted them over the years. In my opinion, this is the purpose of any acquisition of knowledge, to make it one's own.

Whether you use this book as an introduction to a new subject or to further existing knowledge, I hope you will find the creative scope that mouldmaking and casting offers as exciting and fulfilling as I have and do.

Nick Brooks

'Augustus'. Ancient Roman emperor. By Nick Brooks. Cold-cast resin bronze. H 27cm, W 17cm, D 10cm.

CHAPTER 1

HISTORY

The Beginning of Mouldmaking

Long before humans walked the Earth, countless species of animals stamped their footprints in the mud. Fossilization has turned some of these footprints into moulds from which present-day anthropologists, using modern plastics, are able to make casts for scientific records and museum exhibits. The Earth itself was therefore the first mould.

To recreate the visual world in three dimensions was an astonishing cognitive leap for humanity. Many creation myths name clay as the material from which gods or goddesses made the first humans and animals. We know that Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers made small, portable human and animal figurines, usually of ivory, stone, bone or clay. One of the earliest known baked clay sculptures, the 26,000-year-old Venus figurine found at Dolni Vestonice in Moravia, shows that clay was fired at an early date.

The ritual burial of objects of cult significance, often in the form of small animal and human figurines, has occurred in almost every culture throughout the world. The Ancient Egyptian Ushabti figures, the remarkable figures from the island necropolis of Jaiana of the classical Mayan period ( AD 700-800) and the more recent painted terracotta Mexican sculpture are some examples. The urge to make the 'one' into the 'many' has long inspired humanity to replicate those objects found to be beautiful or useful. A proficiency in sculptural mouldmaking generally appeared in societies where organized religion or burial customs required votive images, symbolic objects as offerings to the gods and tomb figures to be buried with the dead. Initially these were handmade by the women or shaman of the tribe, but with the coming of more formalized religious practices the demand for repeated designs increased and as a result various techniques of moulding were used to speed up the output. In many cases, moulding was used in conjunction with hand modelling of faces, hands and other details so as to individualize each figure. The craft became specialized, often resulting in a high degree of artistic production.

An example of such a sequence of events, spanning many centuries, can be seen in China, where an impressive Neolithic ceramic tradition paved the way for the unparalleled skill in moulding of the Shang Dynasty (1523-1 027 BC ). Human sacrifice originally played a prominent part in burial traditions, but when the practice was outlawed tomb figures were required in large numbers as symbolic substitutes. The most famous example in China is the terracotta army of Shih Huang Ti at Xian, C.200 BC , in which the trunks are moulded but no two faces are the same. The beautifully expressive terracotta Tang figures of around the eighth century AD were perhaps the ultimate artistic achievement in the production of tomb figures. For these, both press moulds and multiple moulds were used, with the figures and animals being finished by hand modelling and the use of richly coloured glazes. The same techniques were used for other sculpture intended to provide inspiration for the living. The larger-than-lifesize Lohan Buddhas of the tenth to thirteenth centuries AD were possibly moulded from an admired original, then individualized by modelling before being fired, often in one piece - an impressive feat for such a large statue.

The discovery of new materials ensured the continued development of ceramic techniques. Around the fourth century AD the Chinese invented stoneware, and by the eighth century porcelain had been perfected. A wide variety of techniques again combined moulding with modelling to produce porcelain statuettes for domestic shrines. These figures in white porcelain, which came to be known in Europe as blanc de chine, were among the most prized works of Eastern art in Europe in the early eighteenth century. Copies of small figures of the Buddhist Bodhisattva Gwanyin were amongst the earliest works sold by the Royal Saxon Porcelain Manufactory at Meissen.

Next page