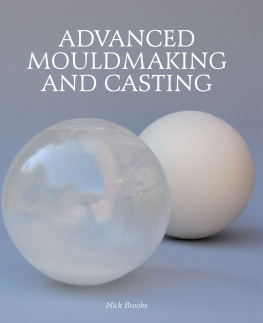

Embedded polyester resin.

ADVANCED

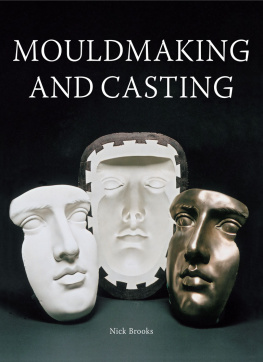

MOULDMAKING

AND CASTING

Nick Brooks

First published in 2011 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

Nick Brooks 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 723 6

Disclaimer

The author and publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it

DEDICATION

To Linki and Jake

FOREWORD

What is the purpose of moulds and casts? And why does the Royal Academy of Arts mount an exhibition of Modern British Sculpture using in its poster a detail of an exact replica over 2 metres square of part of Olaf Street in London, made by the Boyle Family in 1966?

By making moulds and casting from them a unique and new form can be transformed in its material. A more durable or more beautiful or more expressively appropriate material is substituted for the original material, which was in its time appropriate for the discovery of the form. This is the use of making moulds and casting in the origination of an individual work of art.

Alternatively, a form recognized as valuable can be produced en masse, as a multiple, as we call works of art that no longer rely on their uniqueness to gain prestige. The same process is used in industries that make useful objects, indistinguishable from each other. The 100,000,000 sunflower seeds in the installation Sunflower Seeds by Ai Weiwei at Tate Modern in 2010 must set a record for quantity cast. It also set a record for the individuation of multiples. Each cast was finished and coloured by hand, and it may be said that no two are identical. The unique also remains important in utilitarian productions, as millions of crowned teeth in the mouths of old people can testify.

The reproduction of objects mirrors biological reproduction itself. Humanity, instinct with a sense of its own value, has the urge to reproduce sexually. The same urge goes back billions of years to the earliest form of life. From its beginning, society created what we now call works of art, as religious objects for use in ritual. An artist was required to conform to a traditional mode of representation, and religion might even require details to be incorporated that could not be seen by the worshipper. In medieval Japan statues of the Buddha were cast in lacquer. These figures sometimes hid carefully cast feet within shoes that have only been broken open by accident more recently. The combination of a liquid that sets with fibrous reinforcement was the basis of Japanese casting technique. The liquid was drawn from the lacquer tree, the fibre was hemp or cotton. The expansion of Buddhist monasticism was such that in 700CE the Emperor ordered every household to plant lacquer trees. A connection between then and now can be seen in the use of contemporary resins with glass fibre reinforcement.

Putting metal aside, with its dependence on high temperatures, clay, plaster and wax form a triumvirate of traditional materials, whose strengths and weaknesses complement each other. Things made in any of them can resist entropy. The first sculpture that Degas exhibited failed to gain critical approval. Thereafter he left in wax many wonderful works, suitable for casting in bronze. They have survived, with some disputed distortions, the best to be finally cast in a more durable ma terial. Posthumous fame has conferred similar resurrections on many pieces of sculpture by twentieth-century artists for whom recognition came late.

Around 1900CE an awareness of the interplay between positive and negative versions of the same surface developed, perhaps because of the ubiquity of moulds and casting. Abstract sculptors such as Gabo came to work with thin sheet surfaces having visual access to both sides. The language of Cubism invited sculptors such as Zadkine to integrate both within a single figure. The exchange of negative and positive was demonstrated on a grand scale by Rachel Whitereads House which stood at 193 Grove Road in London from 1993 to 1994. There, the mass of a wall was converted into a narrow space, and the volume of a room was converted into a solid block.

In his influential essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936), Walter Benjamin wrote: from a photographic negative one can make any number of prints; to ask for the authentic print makes no sense. He deplored the exaggerated value placed on the uniqueness of art objects, and the mystical aura with which they were endowed. He thought that from 1900 onwards the technical means existed to free art from its roots in religious practice, free it, he hoped, to engage with the practice of politics.

In the post-modern situation a variety of aesthetic convictions exist alongside the political. Consider Brian Haws protest against the UK governments policies in Iraq. From 2001 till 2006 he camped in Parliament Square. He assembled some 600 banners and other items of protest. Everything in that assemblage was reproduced by the artist Mark Wallinger, in an installation State Britain at the Duveen Galleries, Tate Britain, in 2009. In such projects as this, the skills of mould-making and casting can play a crucial role. After their Olaf Street Study in 1966, the Boyle Family went on to replicate 100 randomly chosen sites in London. From that they proceeded to a global selection of samples to represent the earth. Whatever the motives and aesthetic convictions of a sculptor, the methods of making moulds and casting from them, which are taught by Nick Brooks, and which he has described with such clarity in this book, will prove of immense value.

Ken Adams

Former Senior Lecturer at St Martins College

of Art and Design

INTRODUCTION

In producing Advanced Mouldmaking and Casting my aims are to provide a book that can be used both to advance levels of pre-existing skills and to introduce new techniques and materials that may not have been used previously by the reader. The content builds upon and goes beyond the fundamental techniques and principles described in the precursor to this book, Mouldmaking and Casting (The Crowood Press, 2005).

Some of the processes and materials covered are traditional, and the reader may have had some experience of them before. Hopefully this book will address any problems encountered with these. Other processes and materials in the book are relatively new to the subject, being in use in industry but only recently available on the smaller-scale domestic market. It is hoped this book will encourage further levels of exploration and experience of the subject.

Mouldmaking and casting is, of course, not a finite process and the reader may choose to reinterpret certain processes. The options for a particular project are often multiple and varied depending on the requirements of the maker. The aesthetic, economic and timetabled requirements of the particular project in hand will all inform those options in a multitude of different ways. Having the specifications and technical practices for the processes and materials is only the foundations for a project; what the maker does with that information is what ultimately informs and inspires the work. It is hoped that this book can be a part of that process.

Next page