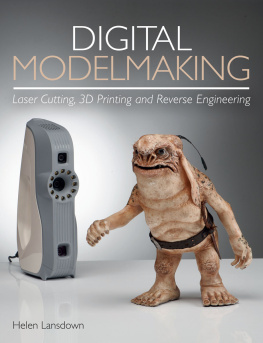

DIGITAL

MODELMAKING

Laser Cutting, 3D Printing and Reverse Engineering

DIGITAL

MODELMAKING

Laser Cutting, 3D Printing and Reverse Engineering

Helen Lansdown

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

Helen Lansdown 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 586 2

DEDICATION

To my family, Ken & Jean, Denise, Vic & John. A big thank you to all of the contributors and special thanks to my wonderful friend Claire, without whom I would not have finished.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The contributions of students and industry professionals are gratefully acknowledged; Justin Adaire Hugill, Rebecca Smyth, Fenella Lundburg, Felix Burke, Paulina Grenda, Jason Larcombe, Isobel McI- nnes, Cora Prazeres, Bobs Bits, The Alternative Limb Project, Ian McQue, Ben Twiston-Davies, 3DD Ltd, Berry Place Ltd, FBFX Ltd, John Beaufoy and Chris Beach. The author would also like to thank the photographers: BJP Photography, Sonke Faltien and Omkaar Kotedia.

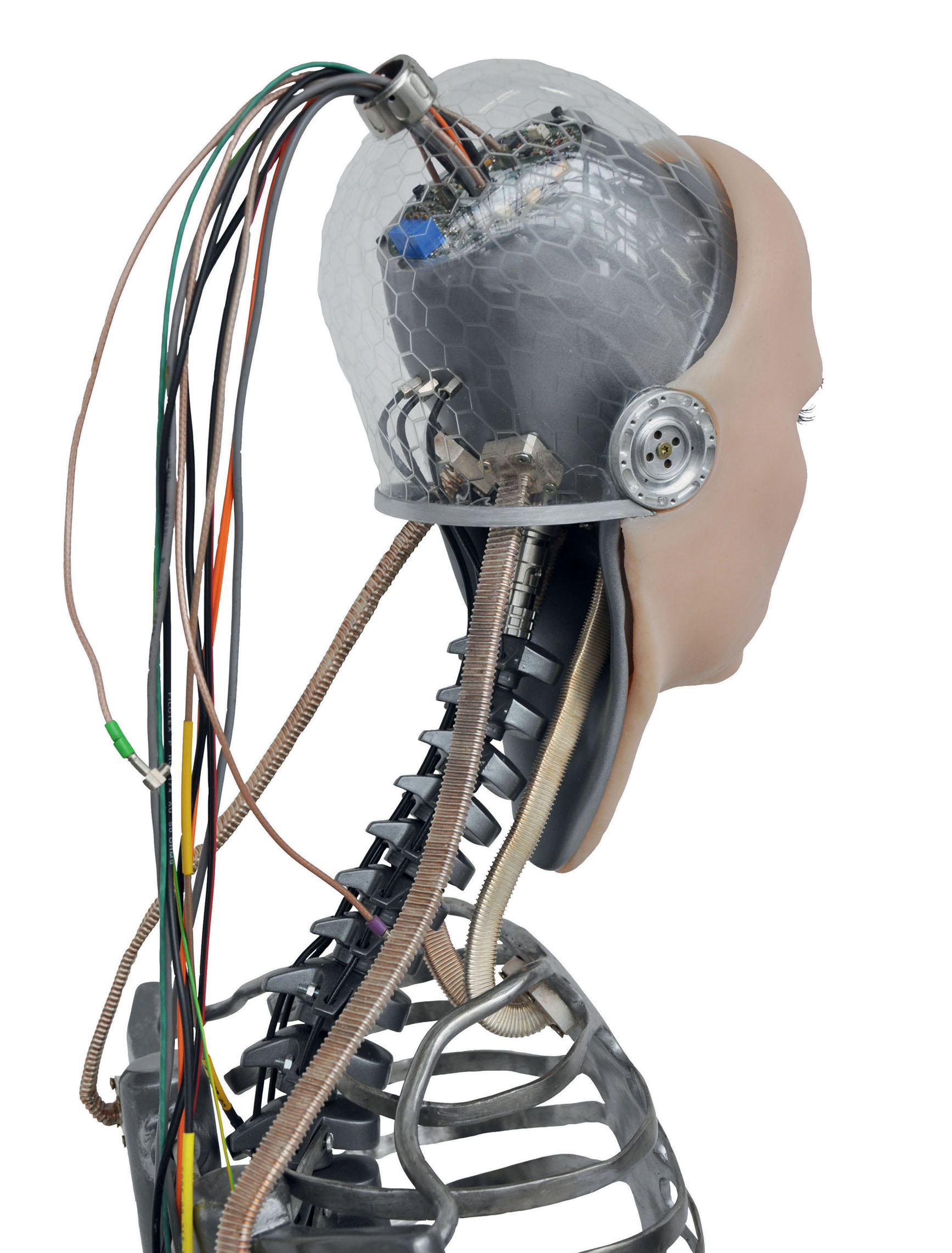

Frontispiece model and photograph by Rebecca Smyth, model owned by Bob Bits.

DISCLAIMER

The information and techniques given in this book have been tried and tested by the author, but the author and publisher cannot be held responsible for any resulting injury, damage or loss to either persons or property. It is the responsibility of the reader to be aware of the correct health and safety procedure for all products, machines and materials that they use.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Model by Fen Lundburg. BJP PHOTOGRAPHY

This book is intended for students and recent graduates working in the modelmaking industry and individuals with a passion for design and making. The definition of the modelmaking industry will mean different things to different people, depending on the specialism of the practitioner, but the fundamental skills remain broadly the same. The term modelmaker does not adequately represent the breadth of expertise and knowledge that is possessed by a practitioner. A modelmaker is a designer and an expert on materials, manufacturing processes and technology. The techniques illustrated in this book apply to most areas of modelmaking in the creative industries, including film and TV, architecture, product and packaging design, and theatre.

The focus is on digital technologies, which have been introduced into the industry since the 1990s and have made a significant impact on the way in which companies operate. Digital technologies do not replace traditional methods of making models; they are complementary tools that have become integrated into a practitioners toolkit. This book contains information on threedimensional (3D) printing, 3D scanning, photogrammetry, laser cutting, computer numerical control (CNC) machining and 3D drawing software, from the perspective of a modelmaker. Experience of two-dimensional (2D) and 3D computer-aided drawing, and a basic understanding of model construction is helpful, but not essential.

HOW THIS BOOK IS ARRANGED

Each chapter is predominantly dedicated to one subject and written to stand alone, which means that there is some overlapping of information. The reader will occasionally be asked to refer to another section of the book to keep the duplication of content to a minimum. The first section of each chapter contains technical information and useful techniques for each topic. The mid-section provides examples of how these techniques are used to make models. In each of these examples, a description of the design process and software commands that were used to build the models is given, but it is impossible to give a step-by-step guide. Rhino 3D and Illustrator were predominately used to draw the models; it is possible to replace both of them with other software, the command names and approach to drawing are similar in other vector and non-uniform rational basis splines (NURBS) modelling software.

Several case studies from professional and student modelmakers feature at the end of each chapter. These projects are intended to provide context and inspiration. Most of these case studies use a combination of techniques and could, therefore, feature in several of the chapters.

Many of the processes featured in this book need expensive professional-standard equipment and software. Where this is the case, free and easily accessible alternatives are given that provide an opportunity to try the technique without spending money.

Important Note A variety of materials and chemicals feature in this book, it is essential to read and understand the health and safety instructions for each product. Basic information on health and safety is provided in Chapter 1.

MODELS

A physical model is a tangible object that is easier to understand than a computer-generated model. A model is a 3D physical representation of an object made to a scale. For many practitioners, however, the term model will mean different things. For some, a model is a reduced-scale building produced for architectural design, whereas for others it might be a life-size prop for a film. Models can be exact replicas of existing objects or representations of new designs and concepts; they are smaller, larger or made at a life-size scale. Models have many functions: they are used to convey a design intent or as a means of communicating and expressing ideas; they are either one-off commissions or small batch production runs. There are many terms to describe them, including: sketch models, mock-ups, prototypes, concepts and mechanical and display models. They are a feature of numerous disciplines, including product, packaging, toy and automotive design, museums, costume, props and special effects for film and TV; the list goes on. They have different applications, e.g. in product design, they might test a product before it is manufactured or in architecture the client might need a model for planning approval. Whatever the application, the fundamental techniques, materials and processes are the same.

WHAT MAKES A GOOD MODEL

Good models come from good design; they require extensive planning, research, methodical construction and a skilled practitioner to build them with meticulous attention to detail.

ATTRIBUTES OF A MODELMAKER

A modelmaker is a highly skilled, creative designer and artisan of 3D models. They need the technical ability to be proficient with traditional workshop equipment, such as bandsaws, disc sanders and lathes, and possess an understanding of digital technologies, including laser cutting and 3D printing. They have an appreciation of the properties of materials, how they behave when cut, machined and fabricated. They are problem-solvers and innovative designers who can solve complicated technical problems and who can work collaboratively with other people and disciplines.

THE ROLE OF A MODELMAKER

There are various career paths and numerous opportunities for work within the creative industries, including film and TV, architecture, product and packaging design, and theatre, and within each profession, the role of a practitioner will be different. A practitioner can choose to specialize in one aspect of modelmaking and work as part of a team to build a model. This will mean that they are responsible for a single operation, e.g. CNC machining or moulding and casting. They can also choose not to specialize and be solely responsible for an entire project from start to finish. Generally, the larger the company, the more likely it is that a modelmaker will be asked to specialize and work as part of a team alongside specialists in different disciplines; this is simply because it is a more cost-effective way of working. In a smaller company, it is the opposite and a practitioner will have a broader range of skills. In this situation, the practitioner will subcontract elements of the project that they cannot manufacture to external suppliers. Many people choose to work in one discipline, e.g. prop-making for the film and TV industry, but others move between film and TV, architecture and product design, going where the work is.

Next page