ARCHITECTURAL MODELMAKING

SECOND EDITION

First published in 2010

by Laurence King Publishing Ltd

361373 City Road

London EC1V 1LR

Tel +44 20 7841 6900

Fax +44 20 7841 6910

E

www.laurenceking.com

Second edition published in 2014

by Laurence King Publishing Ltd

Design copyright 2010 & 2013 Laurence King Publishing Limited

Text 2010 & 2013 Nick Dunn

Nick Dunn has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs, and Patent Act 1988, to be identified as the Author of this work.

Technical consultants: Jim Backhouse and Scott Miller

http://blogging.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/sedlab/

www.makecollective.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book from the British Library

ISBN 978 178067 172 7

Series design by John Round Design

This edition by Matt Cox at Newman+Eastwood Ltd.

Printed in China

NICK DUNN

ARCHITECTURAL MODELMAKING

SECOND EDITION

Laurence King Publishing

Contents

Related study material is available on the Laurence King website at www.laurenceking.com

Introduction

Why we make models

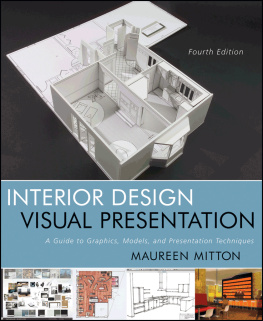

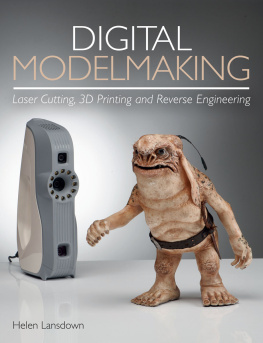

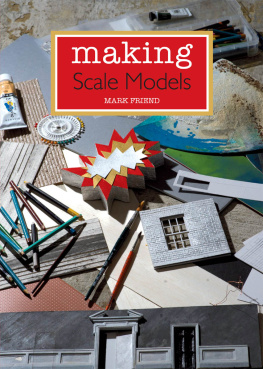

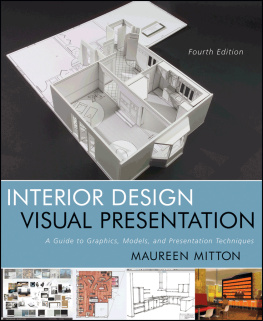

The representation of creative ideas is of primary importance within any design-based discipline, and is particularly relevant in architecture where we often do not get to see the finished results, i.e. the building, until the very end of the design process. Initial concepts are developed through a process that enables the designer to investigate, revise and further refine ideas in increasing detail until such a point that the projects design is sufficiently consolidated to be constructed. Models can be extraordinarily versatile objects within this process, enabling designers to express thoughts creatively. Architects make models as a means of exploring and presenting the conception and development of ideas in three dimensions. One of the significant advantages of physical models is their immediacy, as they can communicate ideas about material, shape, size and colour in a highly accessible manner. The size of a model is often partially determined by the scale required at various stages of the design process, since models can illustrate a design project in relation to a city context, a landscape, as a remodelling or addition to an existing building, or can even be constructed as full-size versions, typically referred to as prototypes.

Throughout history, different types of models have been used extensively to explain deficiencies in knowledge. This is because models can be very provocative and evoke easy understanding as a method of communication. Our perception provides instant access to any part of a model, and to detailed as well as overall views. Familiar features can be quickly recognized, and this provides several ways for designers to draw attention to specific parts of a model. A significant advantage of using models is that they are a potentially rich source of information providing three dimensions within which to present information, and the opportunity to use a host of properties borrowed from the real world, for example: size, shape, colour and texture. Therefore, since the language of the model is so dense the encoding of each piece of information can be more compact, with a resulting decrease in the decoding time in our understanding of it.

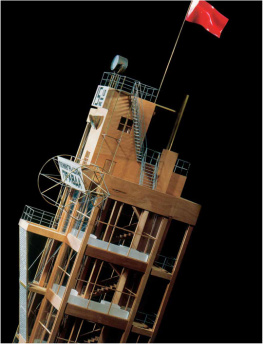

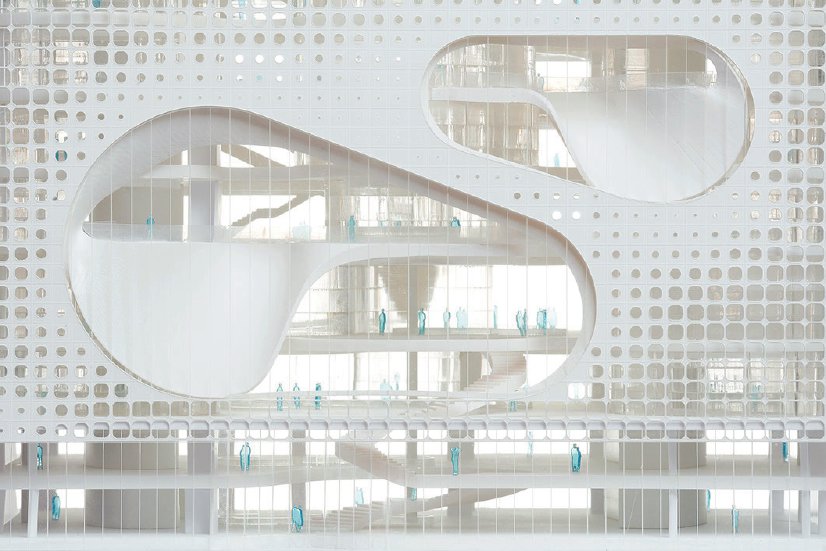

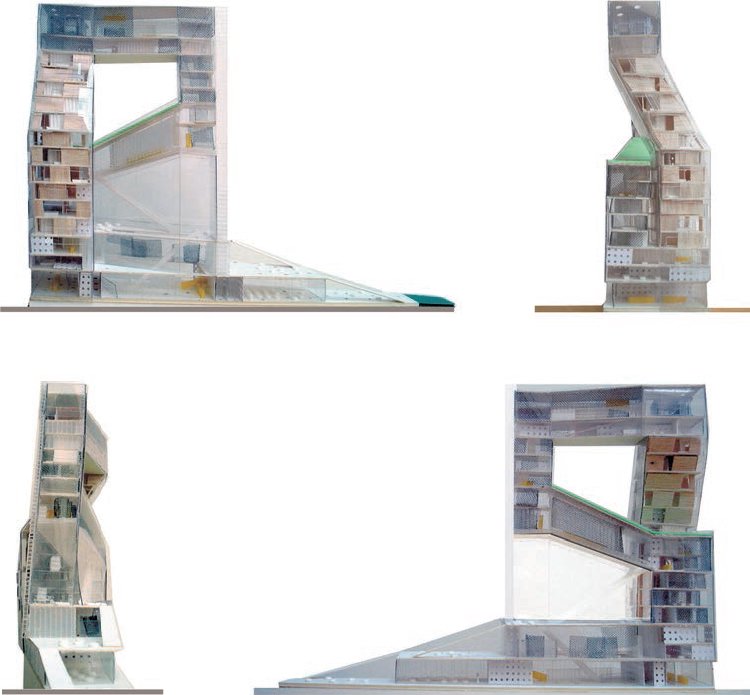

Members of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), with a design development model for the Universal Headquarters, Los Angeles.

In order to understand architecture, it is critical to engage in a direct experience of space. As Tom Porter explains in The Architects Eye, this is because architecture is concerned with the physical articulation of space; the amount and shape of the void contained and generated by buildings being as material a part of its existence as the substance of its fabric. Considered in this manner, the discrimination on behalf of the modelmaker to decide which information to include, and therefore which to deliberately omit, to best represent design ideas becomes crucial.

As practitioners, architects are expected to have a highly evolved set of design skills, a core element of which is their ability to communicate their ideas using a variety of media. For the student learning architecture, the problem of communicating effectively so that the tutor may understand his or her design is central to the nature of design education; spatial ideas can become so elaborate that they have to be represented in some tangible form so that they can be described, explored and evaluated. This situation becomes complicated since crosstalk occurs between different However, this delivery of ideas is not simply for the benefit of a tutor or review audience. The modelling of an architectural design has important advantages for a student during the design process as he attempts to express his ideas and translate them, allowing the designer to develop the initial concept. However, it is important to emphasize the performative nature of models at this point since they, as with other media and types of representation, are highly generative in terms of designing and are not simply used to transpose ideas. This establishes a continuous dialogue between design ideas and the method of representation, which flows until the process reaches a point of consolidation. This latter point is important and something we shall return to again and again throughout the course of this book.

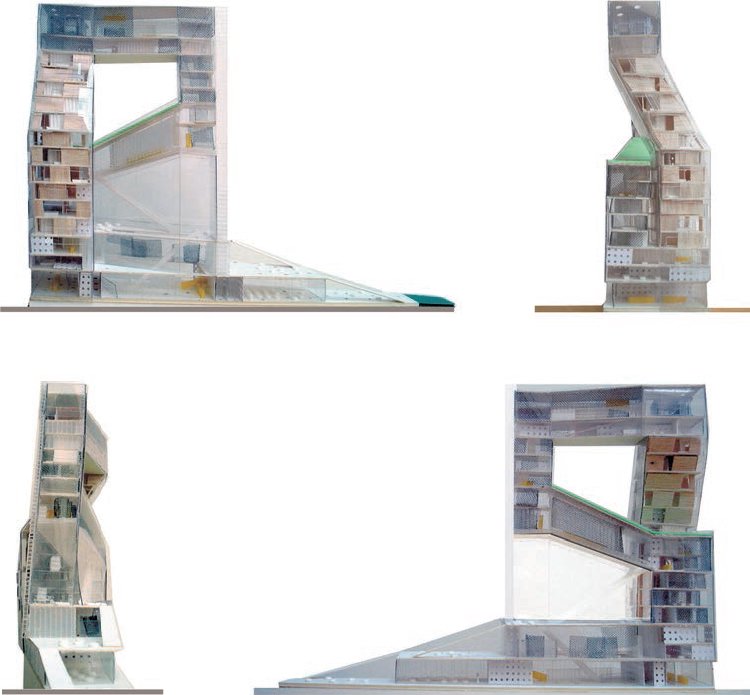

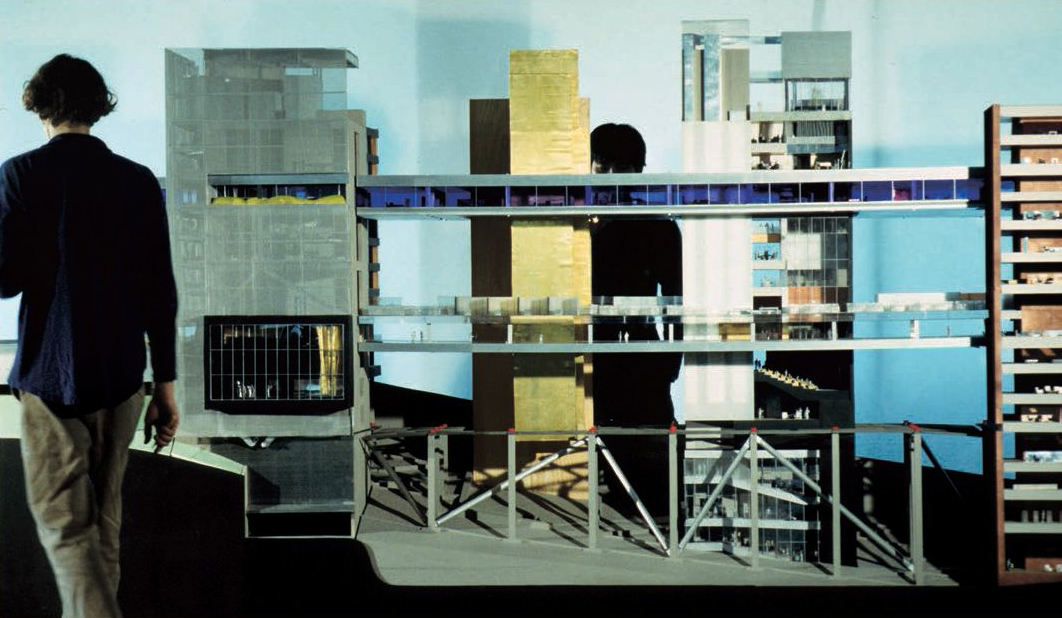

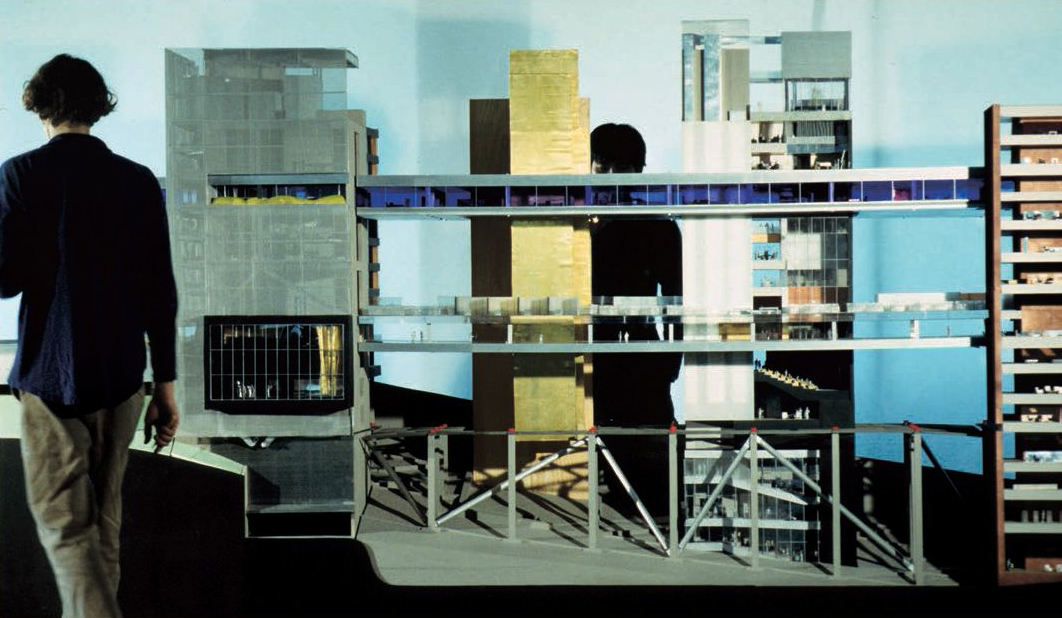

The team at the in-house modelmaking facility at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners works on a 1:200 model of The Leadenhall Building, London.

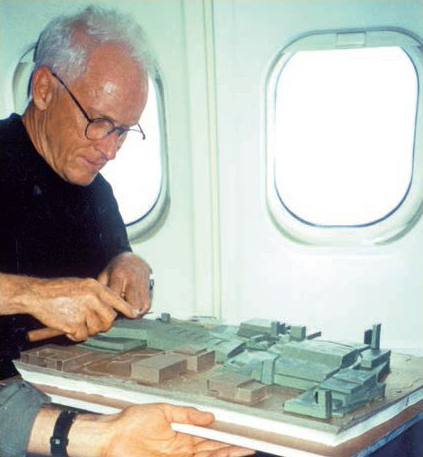

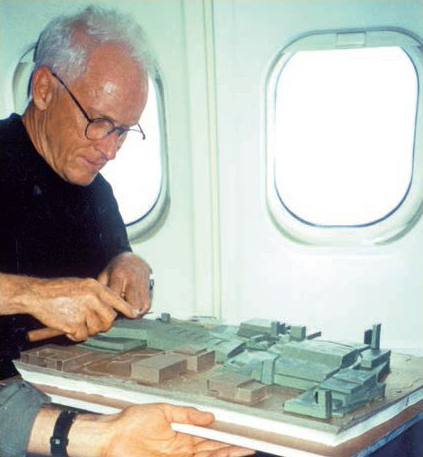

Antoine Predock working on a clay model for Ohio State Universitys Recreation and Physical Activity Center, en route to a project presentation, 2001. On his website, Predock refers to the importance his clay models have within his design process: compared to a drawing on paper, the models are very real; they are the building.

Fundamentally, the physical architectural model allows us to perceive the three-dimensional experience rather than having to try to imagine it. This not only enables a more effective method of communication to the receiver such as the tutor, the client or the public but also allows the transmitter such as a student or architect to develop and further revise the design. As Rolf Janke writes in the classic Architectural Models, the significance of a model lies not only in enabling [the architect] to depict in plastic terms the endproduct of his deliberations, but in giving him the means during the design process of actually seeing and therefore controlling spatial problems

Next page