INTRODUCTION

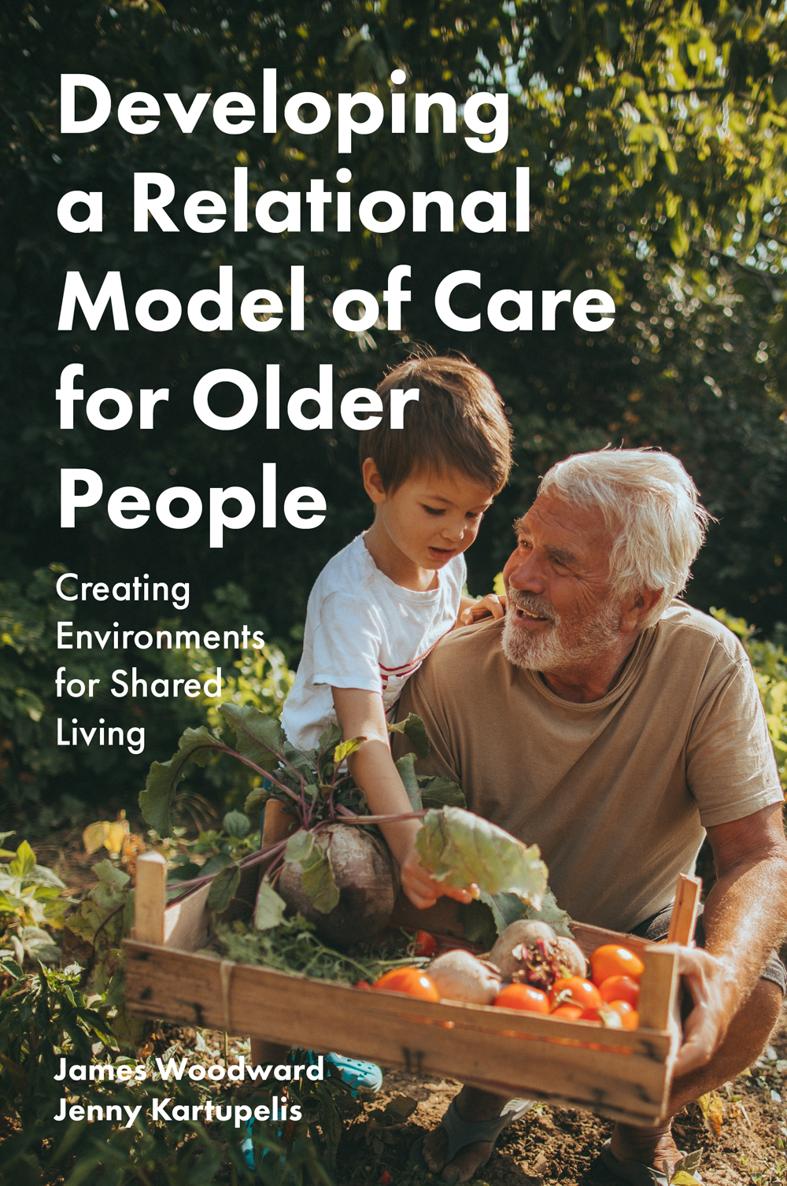

In this book two parallel narratives of professional engagement with age and social care are brought together through a shared interest in the nature of care for older people.

James Woodward has had a long-standing interest in pastoral theology and the nature of spiritual care since working at St Christophers Hospice in south London as a nursing auxiliary from 1982 to 1983. Dame Cicely Saunders who founded the hospice has had a profoundly significant effect upon the reshaping of care at the end of life. This has and continues to be an inspiring influence on the thinking and practice of many who have experienced the quality of care in hospices and through the development of pain control.

This experience led James into healthcare chaplaincy (in Birmingham from 1990 through to 1996) and then into a charity providing housing for older people in an Almshouse Charity in Warwickshire. He established the Leveson Centre for the study of ageing, spirituality and social policy in 2000 and has continued to think about the nature and practice of age and ageing.

Jenny Kartupelis provides research, strategic planning and management services to interfaith and other charitable bodies, and was previously the Director of the East of England Faiths Council for 11 years, an organisation she helped to establish. The Councils main roles were to support local interfaith in the region, act as an advocate for faith in society and work with local and national government. Her professional background is in public relations and research, and it was this expertise that brought her into connection with the charitable work of the Abbeyfield Society, and she was commissioned to deliver a qualitative study about spiritual needs and care in Abbeyfield. In this respect, Jenny contacted James to talk through elements of this process; this conversation has continued and included the organisation of a consultation at St Georges House, Windsor Castle, where James worked from 2008 to 2015.

These conversations have developed into a collaboration in the writing of this book. Both Jenny and James believe passionately in the possibilities that residential and supported care offer for older people. This book presents some of the findings of Jennys research study together with a number of reflections about the nature of living together for older people, and we hope the insights will influence current policy and practice, indicating the societal value of a proven model of relational care.

The underlying assertions in this book are these: that we can again become committed to giving whole-person, loving care of the kind often previously provided by charities and religious communities for the indigent and old, but in a modern context; and that it is possible to reinvest, as a society, in collective living arrangements which provide a combination of supported private space with uninhibited access to the assurances provided by shared living. This stands against much of the recent trend to move away from the provision of residential care to offering support at home for older people.

The provision of care is uneven, and this has particularly been the case with those statutory and voluntary organisations that have provided residential and supported care. While we should remember what it is that many have disliked about residential living, we believe that living together in the right circumstances can be good, enriching and supportive for a fulfilled old age. In fact, it might be argued that our ambivalence about residential homes has much to do with a society that fails to value ageing and thereby seeks to marginalise and devalue this growing number of women and men across our families and communities.

Central to Jennys research has been the discovery that for numerous reasons related to their own histories their understanding, being and spirituality, coupled with some significant economic and financial constraints some people benefit significantly from collective living. We should recognise that most people, for most of their lives, thrive from contact with others, indeed can become who they want to be through such interaction. Others, or maybe the same people, will want loving assistance in managing their lives indeed defining the best of the misunderstood concept of asylum: sanctuary, peace, acceptance and support.

Living with others in a place designed to provide housing and loving service means living in an institution, and we use the word institution in the neutral sense of an organisation and its building. We should escape from the platitudes and from polarised and even distorted social science and economics to the important questions. We should especially escape from the live at home or in a home duality with the assumption that at home is good and in a home is an indication of sadness and failure, considering the ways in which people at different stages may choose to live with others. We need to have a much more energetic and informed conversation and review of the range of living arrangements which best suit numbers of people who want and may thrive on giving and taking support from others.

We hope that this contribution to the ongoing consideration of where older people should live and how they might live together will inform the search for an understanding of what makes some living arrangements satisfactory (even good) and others awful. Society must free itself from the policy drivers that insist that home is best, challenging as we do so the societal attitudes that demand inappropriate, impossible self-sufficiency and a particular type of independence.

In this consideration, we should recognise the complexities and indeed the seemingly contradictory forces at play:

We want to be by ourselves, and we want to be with others.

We want to be self-focused, and other-focused.

We want to do things for others and, forgetting others, to concentrate on ourselves.

We want help and support, and we want to manage on our own, not being a bother.

We want our own place, and we want to share.

We want to live with others around us and feel part of life, and we want to live on our own.

Solutions in social policy terms are not to be found solely in making residential homes or retirement villages a fashionable alternative for those who can afford their fee levels. Perhaps the best answers will be found in allowing for different combinations of contact with others, indeed encouraging different groups of people to develop solutions that suit them and their communities, whether geographical or communities of interest. We acknowledge that such solutions must not be available only for the wealthy and the powerful.

In short, how can we construct places with spaces that nurture loving kindness to older people and through them offer their families and the wider community a quality of connection and relationship? We hope that this book stimulates further debate and action in developing new and improved relational structures and models for care.