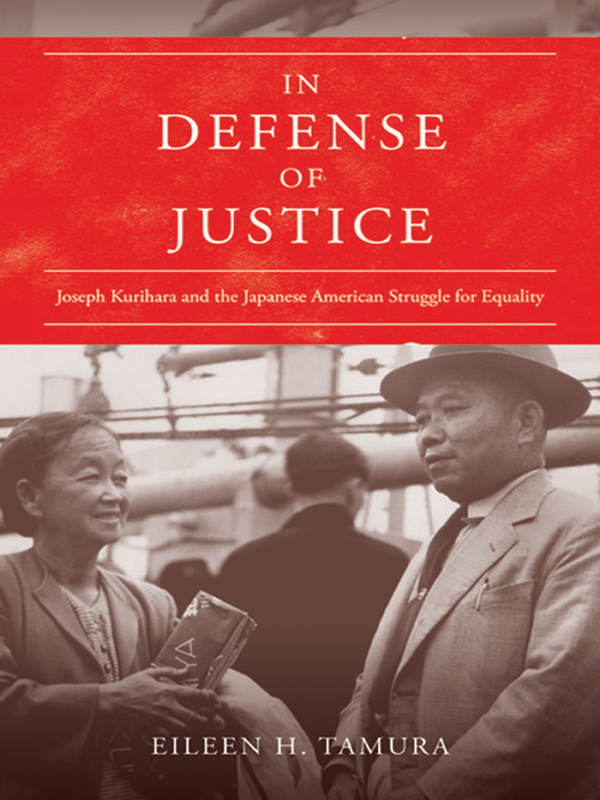

IN DEFENSE OF JUSTICE

THE ASIAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE

Series Editors

Eiichiro Azuma

Jigna Desai

Martin F. Manalansan IV

Lisa Sun-Hee Park

David K. Yoo

Roger Daniels, Founding Series Editor

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

IN DEFENSE OF JUSTICE

Joseph Kurihara and the Japanese American Struggle for Equality

EILEEN H. TAMURA

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield

2013 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

C 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tamura, Eileen H.

In defense of justice: Joseph Kurihara and the Japanese American struggle for equality / Eileen H. Tamura.

pages cm. (The Asian American experience)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03778-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09506-1 (e-book)

1. Kurihara, Joseph Yoshisuke, 18951971.

2. Japanese AmericansEvacuation and relocation, 19421945.

3. Manzanar War Relocation CenterHistory.

4. Tule Lake Relocation Center.

5. Japanese AmericansSocial conditions20th century.

6. Japanese AmericansCultural assimilation.

7. Japanese AmericansEthnic identity.

8. Japanese AmericansBiography.

I. Title.

D769.8.A6T37 2013

940.531779487092dc23 [B] 2013001410

Dedicated to World War II incarcerated Nikkei, especially those whose experiences in WRA camps led to torments known and unknown to others.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Eileen Tamura, whose earlier book in the Asian American Experience series remains the outstanding study of the Nisei of Hawaii, here examines the life and significance of the Hawaii Nisei Joseph Yoshisuke Kurihara (18951965), who became, for a time, the most notorious Japanese American for his role in fomenting the Manzanar Riot of December 6, 1942, during which American soldiers shot and killed two unarmed incarcerated young men. Although Kuriharas actions on the fatal day have figured in dozens of accounts of the ordeal of Japanese Americans during World War II, he has remained, until now, a shadowy figure. Tamura has, through extensive research, discovered and described the pattern of his life in Hawaii, the United States, Europe, and Japan.

In a fast-moving narrative, Tamura traces Kuriharas life on the outskirts of Honolulu and his decision in his teens to switch from a free public school to a Catholic school whose modest fees would have seemed large to him. While many ambitious Nisei, in both Hawaii and on the mainland, opted for Christianity as a way of conforming to American mores, the choice of Catholic Christianity was highly unusual. Tamura explores the dimensions of Kuriharas encounter with Catholicism, which continued after his migration to California, where he attended a Catholic high school and eventually converted. She also explores her subjects encounter with blatant American racism in Progressive Era Californiaquite different from what Kurihara had experienced in Hawaii. Enlisting in the army when the United States went to war, Kurihara served in France and Germany before coming home and resettling in Los Angeles. He graduated from a commercial business college, achieved lower-middle-class economic status during the prosperous 1920s, and maintained it in the Depression. On December 7, 1941, he was at sea as the navigator of a tuna clipper and returned to an America at war with Japan, a place he had never even visited and had little or no interest in. Tamuras sensitive exploration of Kuriharas life after his renunciation of American citizenship and resettlement in war-torn Japan provides for the first time an extended account of those parts of her subjects life.

The most important contribution of this work lies in Tamuras detailed analysis of Kuriharas three-plus years of captivity in various parts of an American archipelago of penal sites built to imprison Japanese Americans of all ages, genders, and beliefs, none of whom were charged with any crime. They were prisoners without trial. Kurihara was originally in the Manzanar concentration camp run by the War Relocation Authoritynot for anything he said or did but because his parents had been born in Japan. Enraged that his government ignored his voluntary military service, he rejected the government. What he said and did at Manzanar resulted in his being sent to even more remote, small, semi-secret penal camps. His final cage was the Tule Lake concentration camp, which had been transformed from a normal American concentration camp into a camp for dissidents and troublemakers who were shipped from the normal camps and penal sites and where the WRA found it expedient to construct a stockadea prison within a prison run by U.S. Army military policewhere conditions were so deplorable that it can be called a precursor of Abu Ghraib. Tamuras exposition and analysis of these facilities and what Kurihara did in them are an important contribution to the history of the wartime ordeals of Japanese Americans.

But also important is her contribution to Japanese American historiography. By the mid-1970s historians were beginning to recognize that what one of its earliest critics had called our worst wartime mistake was instead a logical result of centuries of American racism. Most of the scholarship focused on the loyal victims, most often stressing the heroism of the veterans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. During and after the Vietnam War the focus began to shift to loyal dissenters who refused to go to camp quietly and challenged the government in court, and then to those young men who had resisted the draft in and out of camp without the option of fleeing to a welcoming Canada, which, during World War II, established camps for its Nikkei population. Tamuras lucid account of Joseph Kuriharas wartime rebellion takes the process one step further, pointing to the need for studies of some of the other hundreds who took the path of renunciation and for a deeper examination of the process by which the American government, for the first time, actively facilitated the cancellation of native-born citizenship.

Roger Daniels

PREFACE

I first became aware of Joseph Yoshisuke Kurihara in the late 1980s when I read a passage from his unpublished autobiography. It caught my attention because of its direct, forthright, and passionate style, so different from the image I had of Nisei men. My own observations and what I had read about them indicated characteristics of self-restraint, control of emotions, deference, reticence, nonverbal communication, and composure in the face of hardship. This was not to say that Nisei men lacked feelings, but that they tended to eschew public displays of their emotions. While Kurihara was not the only exception to this generalization, as Arthur Hansen has demonstrated, its validity was strong enough to cause scholarsamong them Frank Miyamoto, Stanford Lyman, Minako Maykovich, William Caudill, Harry Kitano, and Akemi Kikumurato remark on it. Because behavior attributed to the Nisei did not accord with Kuriharas style of verbal assertiveness, confrontation, bluntness, and spontaneity, I wondered, Who was this man?

Following the publication of my book on the Nisei in Hawaii, I began to explore Kuriharas place in the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. I also began to explore his earlier life experiences. After several years of digging, I interrupted my research in order to pursue other projects. When I resumed my focus on Kurihara, I was pleasantly surprised to find that I had no troubledespite the long hiatusin re-immersing myself in the twists and turns of his multilayered experiences. I hope that you will find his story as compelling as I do.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.