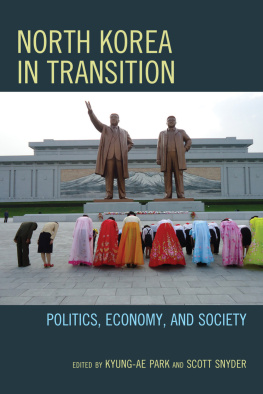

Traveling the 38th Parallel

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Gordon E. and Betty I. Moore as members of the Publishers Circle of the University of California Press Foundation.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the General Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation.

Traveling the

38th Parallel

A Water Line around the World

David Carle and Janet Carle

University of California Press

Berkeley Los Angeles London

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2013 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Carle, David, 1950

Traveling the 38th Parallel : a water line around the world / David Carle, Janet Carle.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-26654-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780520954557

1. Oceanography. 2. Hydrology. 3. Human geography. I. Carle, Janet, 1953- II. Title.

GC28.C37 2013

551.48dc232012030001

Manufactured in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Rolland Enviro100, a 100% post-consumer fiber paper that is FSC certified, deinked, processed chlorine-free, and manufactured with renewable biogas energy. It is acid-free and EcoLogo certified.

This book is for Nick and Ryan, our sons,

and for the world they inherit,

and in memory of Larry Gibson,

Keeper of the Mountain, 19462012.

If nature can heal an injured land, it can heal our... souls as well. Thats why saving Mono Lake is a matter of saving, and healing, ourselves. Lets not change the planet. Let the planet change us.

David Gaines, 1986

Contents

Introduction

Parallel Universe 38 North

You are undertaking the first experience, not of the place, but of yourself in that place... for nobody can discover the world for anybody else. It is only after we have discovered it for ourselves that it becomes a common ground and a common bond, and we cease to be alone.

Wendell Berry (1991, 43)

On June 25, 2010 exactly sixty years after the beginning of the Korean War we stood at the edge of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a 150-mile-long, 2.5-mile-wide strip of land on the 38th parallel that spans the Korean Peninsula. A soldier manning a nearby guard tower stared across the water, ready to strike at any threat from the north. An egret at the river stared into the water, ready to strike at fish. With people excluded from the DMZ for so many decades, the wetlands and forests behind barbed wire have become a haven for wildlife and an inadvertent experiment in ecological recovery.

That Korean experience was part of an around-the-world exploration we undertook along the 38th parallel, seeking water-related environmental and cultural intersections. Latitude lines are part of an abstract grid that humans have superimposed over the globe. Though imaginary, the lines coincide with physical realities dictated by this tilted planets orbit around the sun. People who share a particular latitude, north or south of the equator, also share a specific orientation to the sky and experience the same day lengths during each annual cycle of seasons. Identical constellation patterns span the heavens every night at the same latitude around the world. The latitude and longitude grid helps travelers know where they are, and helps them navigate to destinations and recognize when they have arrived. Exploring a particular line can clarify both physical and cultural routes chosen by humanity, both historically and at this moment in time.

Thirty-eight degrees north (38N) is a temperate, middle latitude where human societies have thrived since the beginning of civilization. Between extremes of climate found farther north and south, successful agriculture and the growth of cities along this latitude depended on many ingenious solutions to the problem of water supply. Altering natural water systems has consequences though, and, at this point in human history, environmental challenges associated with water are ubiquitous.

Our geographical exploration focused on stories of wetlands conservation; groundwater and river pollution; groundwater aquifers threatened by overdrafting for agriculture and domestic supplies; dams and aqueducts to store and transport water hundreds of miles to serve distant farms and cities; water limits generating tensions between cities, states, and nations; and the effects of climate change on the global water cycle. That grim list of challenges and problems was balanced by the inspiring work of scientists, environmental activists, and resource agency employees striving to renew what has been damaged, recover what has been lost, and preserve what remains pristine.

Water is the key to life on Earth, shaping the abundance and patterns of that life even when the influence is indirect. Lakes, rivers, and wetlands are particularly rich places of biodiversity. Adaptations that conserve water are the signature traits of desert plants and animals, while long-distance bird migrations are ultimately a quest to avoid water-freezing conditions, which threaten every water-rich living cell. As an erosion force, water at work explains many landforms. Civilizations have grown, evolved, or failed as they tapped water below ground, captured it behind dams, or moved it across the landscape to supply farmers and city dwellers.

Maps depict crosshairs where the 38N latitude and 119W longitude lines center on the oval expanse of Mono Lake, east of the Sierra Nevada crest, where we worked for two decades as park rangers and still live. The lake is a salty inland sea, too alkaline for fish, but with enormous quantities of algae, brine shrimp, and flies that feed millions of birds. Picturesque tufa towers decorate the shore where springs brought calcium into the carbonate-rich lake and formed limestone spires underwater. The towers were exposed as the lake surface dropped after the city of Los Angeles began diverting streams from the Mono Basin in 1941. A sixteen-year legal battle began in 1978 to save the shrinking, increasingly salty lake ecosystem, pitting concerned citizens and scientists against Los Angeles. In 1994 the David-versus-Goliath contest was won by little David. A small group of leaders with the Mono Lake Committee had built a national organization of supporters and volunteers that prevailed in court, ensuring that the giant city shares enough water with the lake to keep it alive and healthy. Such an outcome offers hope for a world facing many similarly daunting challenges.